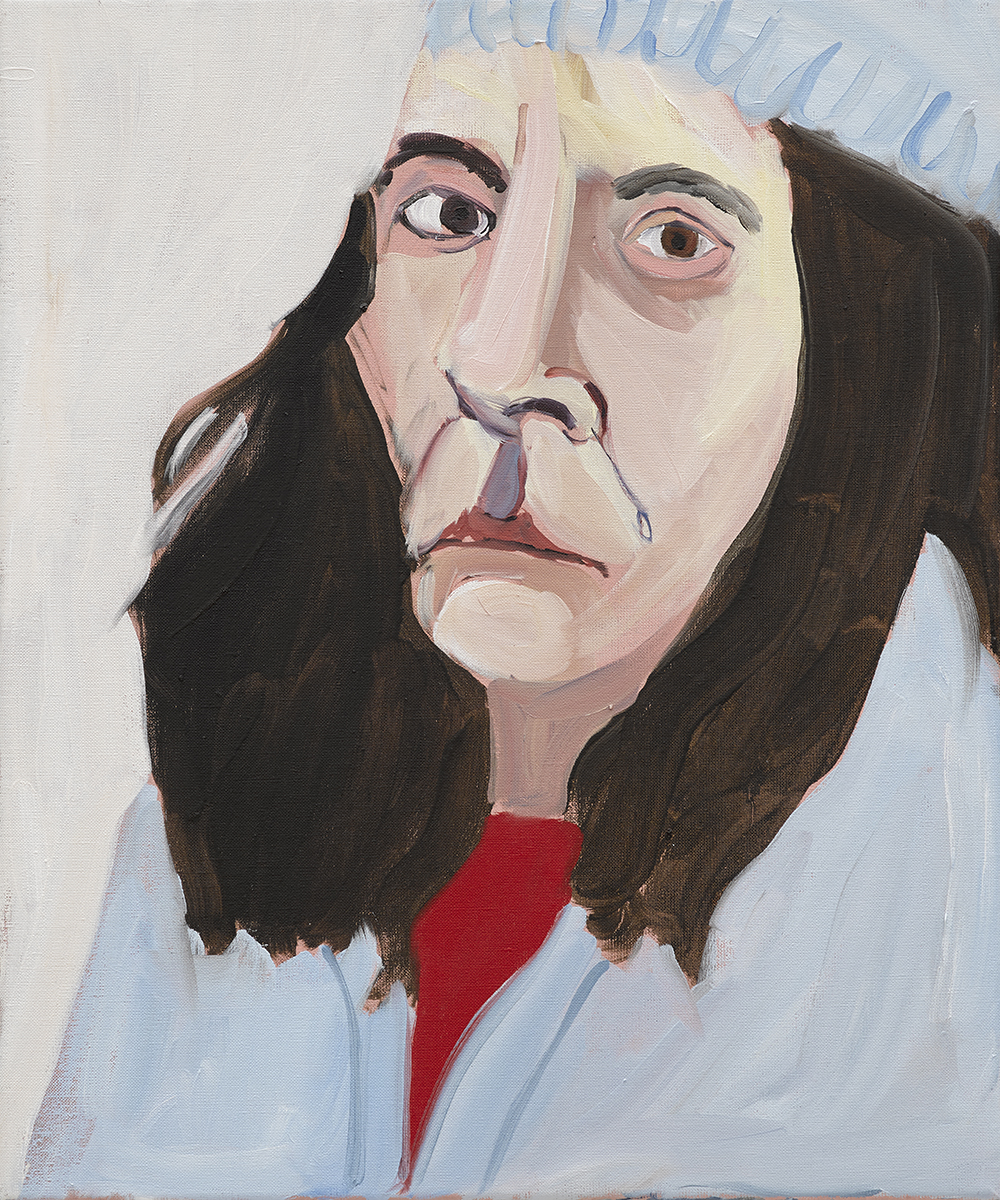

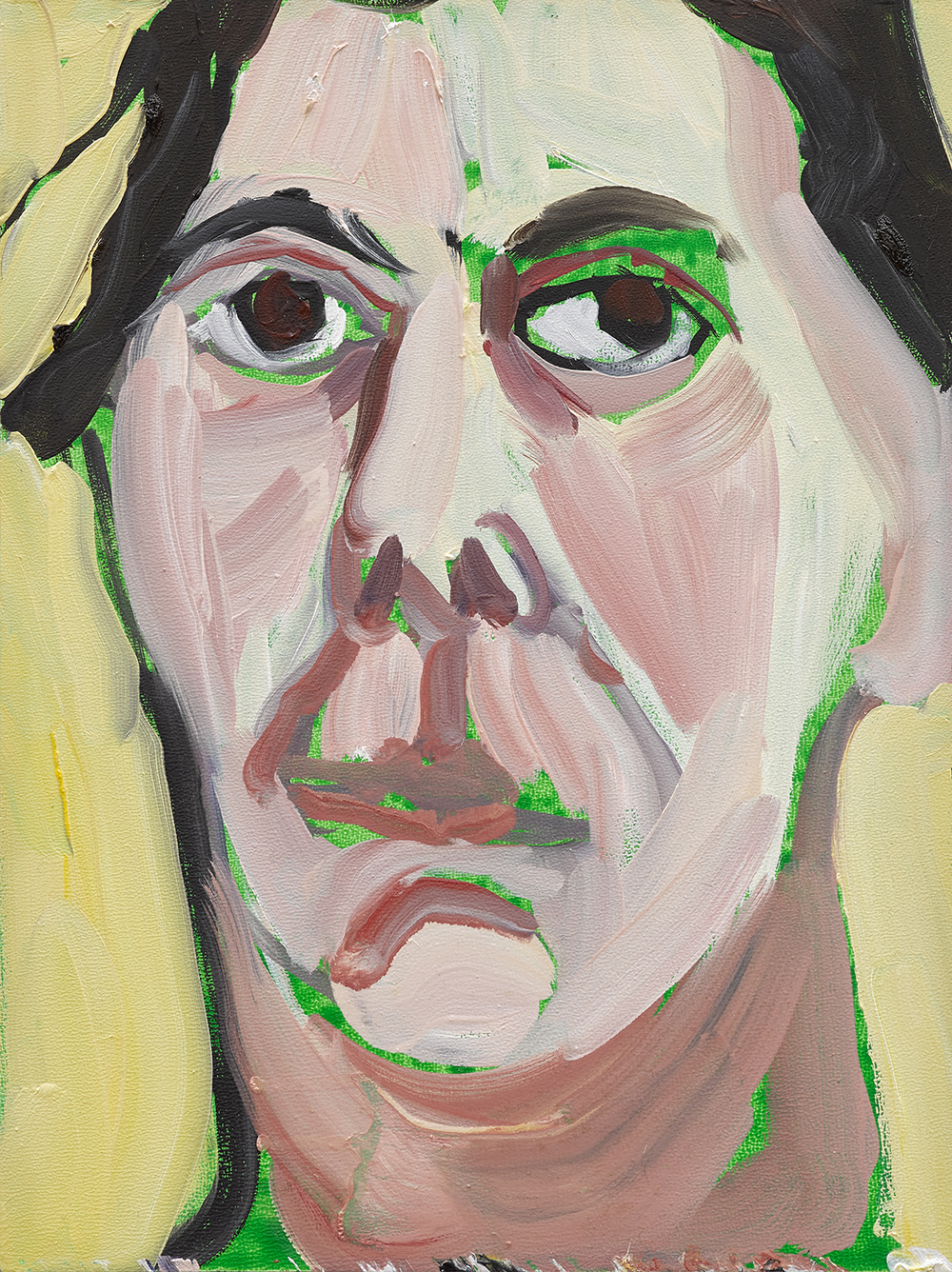

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, 1st January, 2018, oil on board, 24 1/8″ x 18″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Here’s the setup: palette, chair, mirror. The mirror is bandaged together with red-and-white tape that says FRAGILE, but let’s not make too much of that. The original plan was written on a scrap of paper: “small heads—meditations—buy lots of small boards.” The first was painted on January 1, 2018, “the worst day of the year,” not that the rest of the year was that much brighter. Joffe’s marriage was breaking up. She painted herself nearly every day, sometimes at night, always in fairly pitiless light.

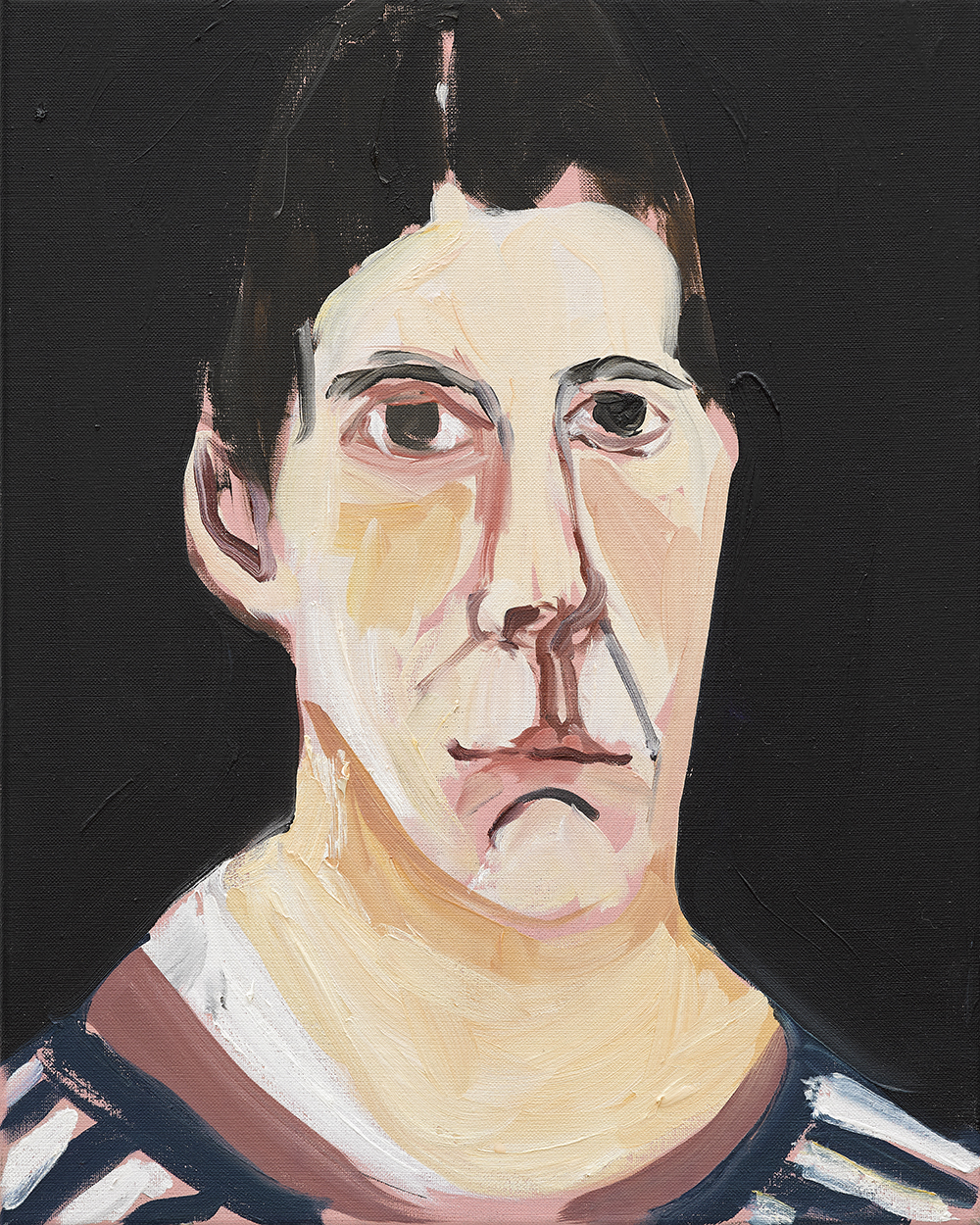

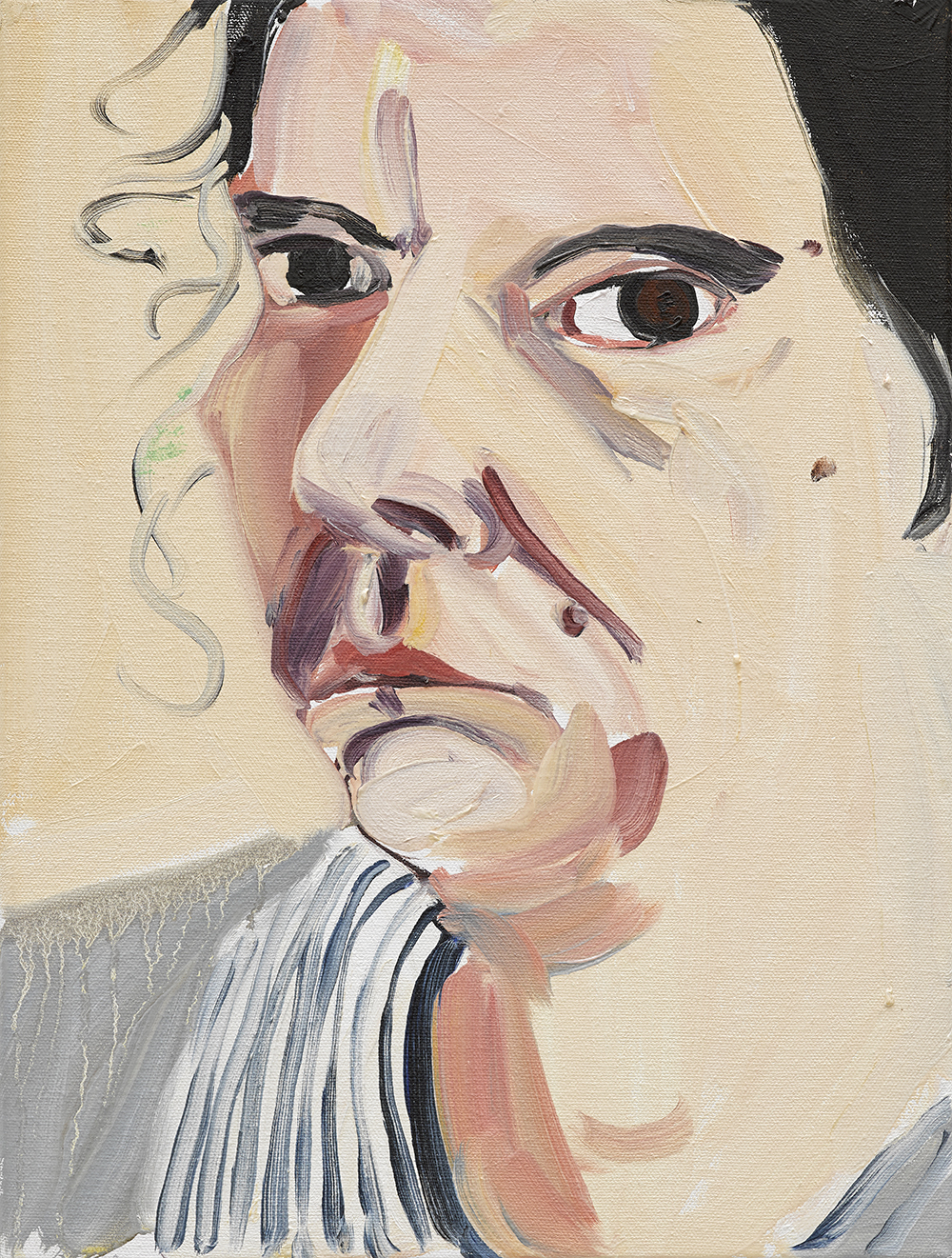

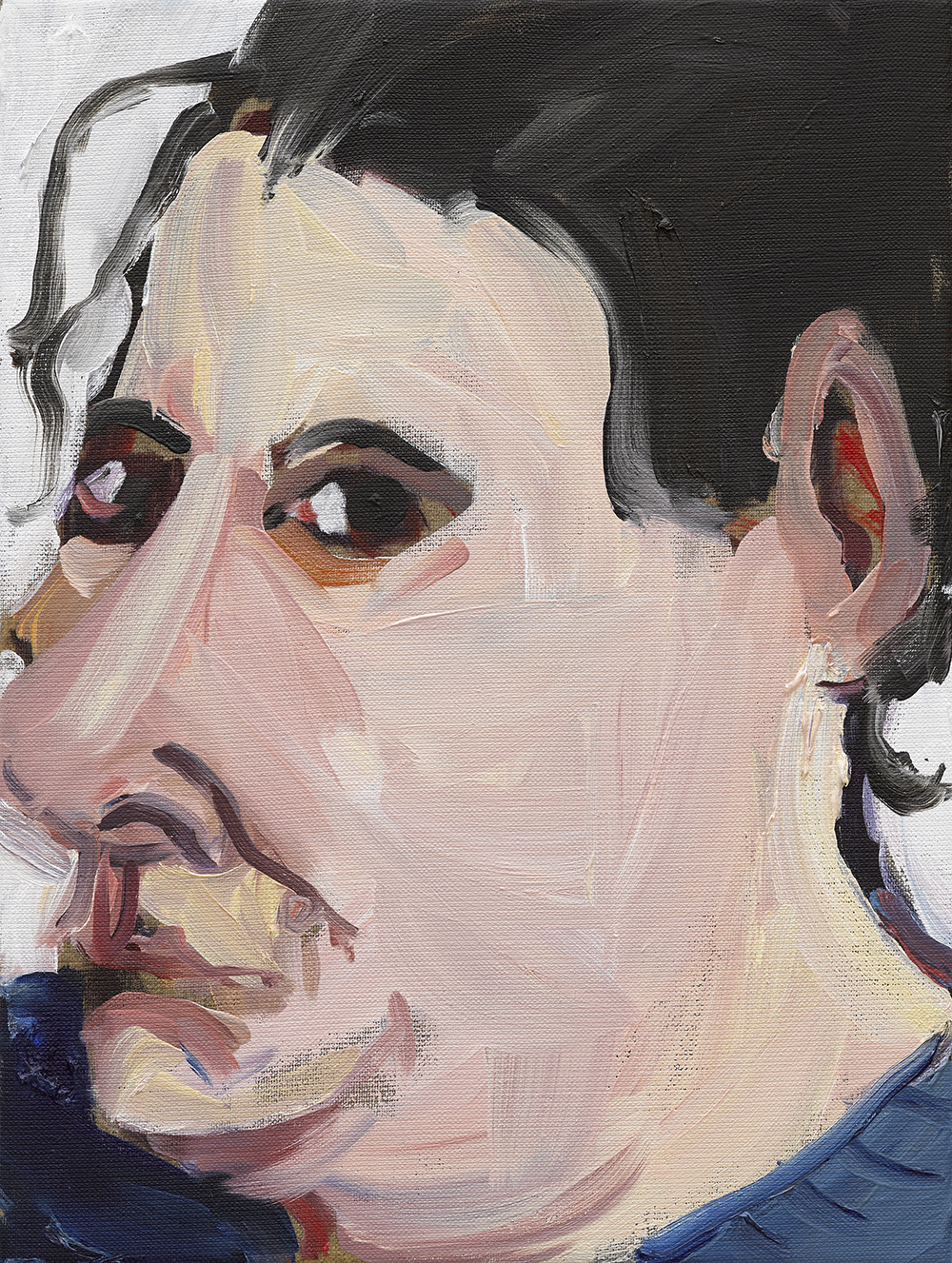

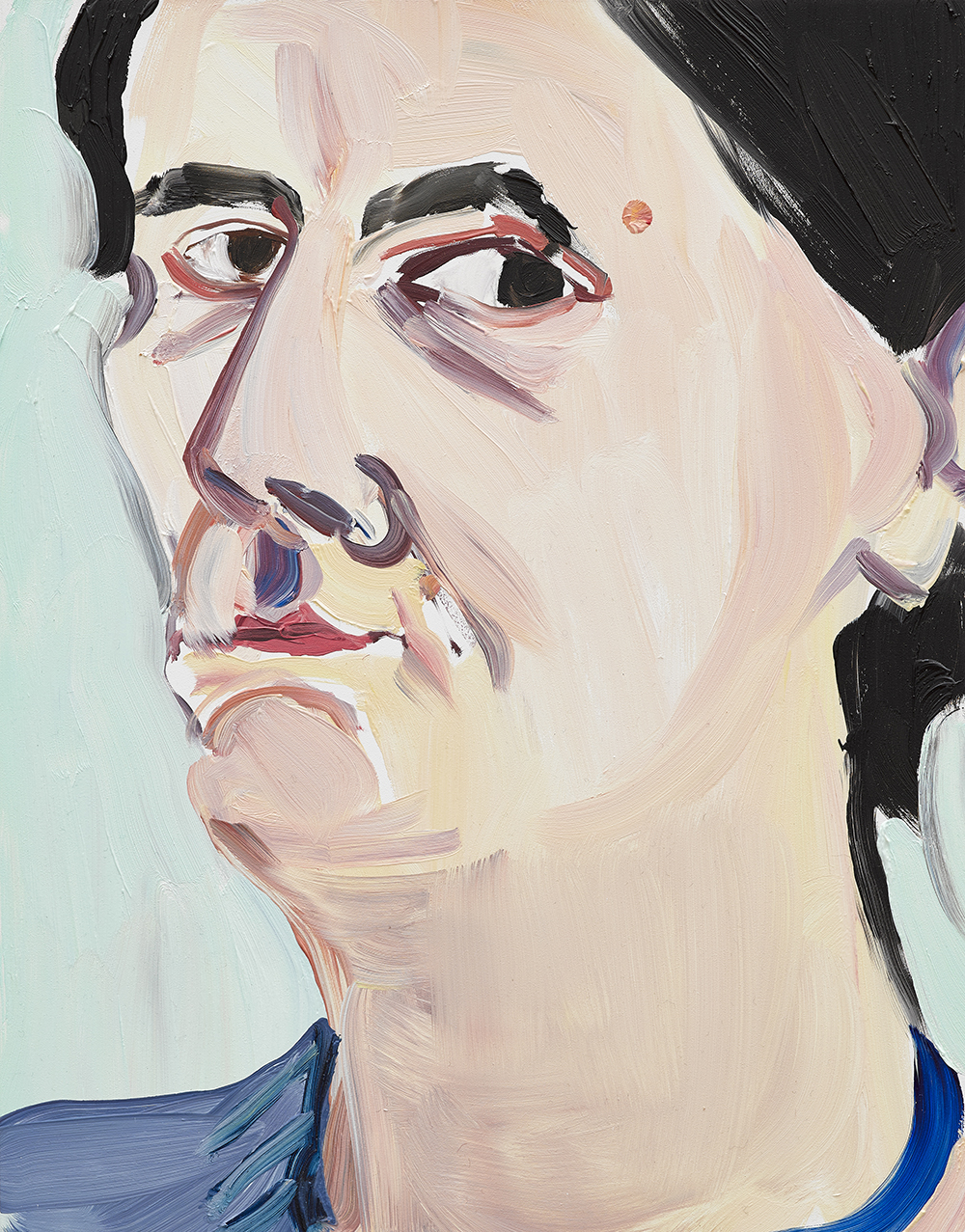

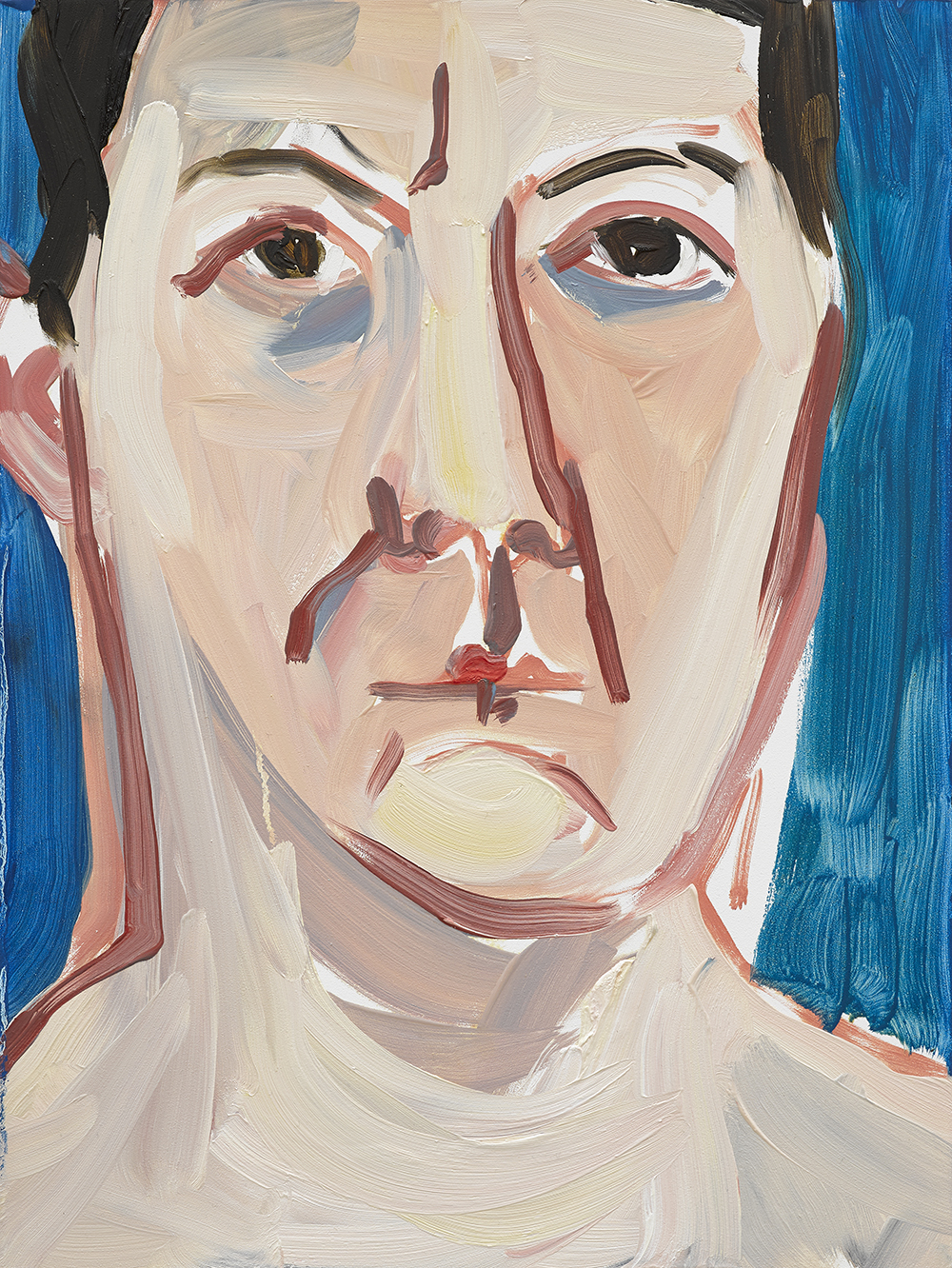

Speaking broadly for a minute, she looks in this extraordinary series of self-portraits like someone almost warping under a heavy weight. Bowed down, weighted by feeling, she peers back at herself, artist prowling after sitter, avid to catch pouches, moles, sags, bags, and quirks of flesh. Maybe at first it looks like someone giving herself a hard time, the visual equivalent of how (women) rail against their face, their thighs. Something funny happens when a woman looks at herself, as if she can’t ever not be narcissistic, flaunting the way she either measures up or doesn’t to the flawless face we all carry around inside the handbag of our heads.

That’s inevitable, you can’t unthink political realities, but it isn’t exactly what’s happening here. The clue, I think, is what it’s like to look at these faces communally, as a chorus. They are so wildly specific, peering at you sideways, each one differently unhappy, each one concrete, present, original as in not a copy of the last.

There’s a poem by W. S. Graham about the death of a loved friend (the painter Bryan Wynter), and in it he says: “I am up. I’ve washed / The front of my face.” The pacing is absolutely that of bereavement and loss, when things are so groundless that the simple act of getting out of bed is an achievement worth recounting. I am up, if hunched and huddled, looking sidelong at my ongoing desolation.

But it’s the front of the face business I want to get at. The front of the face, the bit that gets looked at, as opposed to the thinking/feeling apparatus that ticks away behind the eyes. Time moves in one direction. Unless you’re Benjamin Button, you’re getting older by the second. But emotional states are more like weather systems, moving in and out, and so the face is constantly changing in two ways simultaneously. A long slow look, Lucian Freud–style, literally accretes time on the canvas, but Joffe’s strategy of small and fast might be a better route if what you want to capture is not a permanent or solid self but rather instability, the way that moods temporarily tighten muscles or slash fresh grooves, refashioning flesh in a minute-by-minute way adjacent to but nothing like as permanent as the seismic collapses of age.

Flesh is so funny. Bottom line, it’s there, too too solid as Hamlet had it, and horribly revealing. The older you get the more you give yourself away; the more the you in you seeps out. At the same time flesh isn’t stable at all. Cadaverous yesterday, bloated tomorrow, depending on the particular brand of sadness that’s grinding you down. In the very first portrait, blue cardigan, it’s a double-chin kind of day, nostrils flared, rearing back like a startled horse. Some of the faces are doleful, some reproachful, some crouch behind cheekbones sharp as chisels. Unhappiness can feel like a permanent ecosystem but the evidence of these pictures is that every day was subtly different from the last, and so at the very least thrilling to chart, meditations on an emergency in which the painter gets to play both the red-eyed catastrophe and the dispassionate, erratically tender observer, standing a little distant from herself.

By the summer, Joffe had shifted operations to New York. The light was different and the faces in it look more mobile, less like masks of catatonic grief. The mood has shifted. The wind has changed. But she isn’t stuck at all. Just look at the faces she made.

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, February I, 2018, oil on canvas, 23 5/8″ x 19 5/8″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Chantal Joffe, Night Self-Portrait, March I, 2018, oil on canvas, 19 3/4″ x 15 3/4″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, April I, 2018, oil on canvas, 16″ x 12 1/8″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Installation view, “Chantal Joffe,” Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE, April 11–May 18, 2019. © NS Harsha. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, June II, 2018, oil on canvas, 15 3/4″ x 11 7/8″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, August IV, 2018, oil on board, 12 1/8″ x 9 1/8″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Chantal Joffe, Self-Portrait, November, 2018, oil on canvas, 14 1/8″ x 11 1/8″. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London/Venice.

Olivia Laing’s most recent book is Crudo.

Chantal Joffe: The Front of My Face is published to accompany Joffe’s exhibition at Victoria Miro, London, on view from April 11 to May 18, 2019.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2VF0QDZ

Comments

Post a Comment