Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

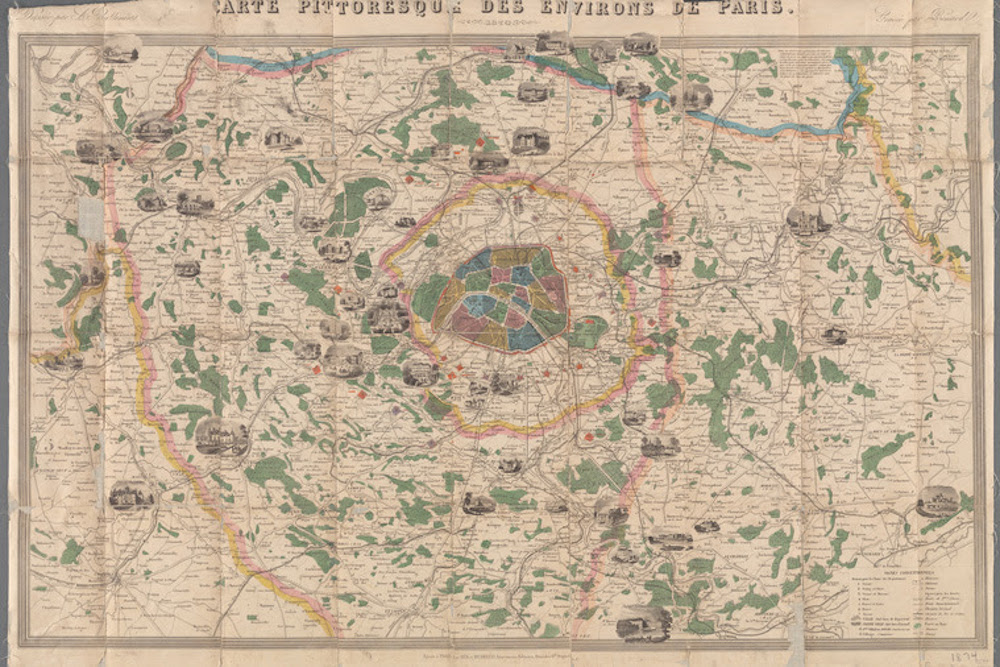

This week, we’re listening to that old jazz standard “April in Paris” and reading Françoise Sagan’s Art of Fiction interview, as well as Zygmunt Haupt’s short story “In Paris and in Arcadia” and Charles Baudelaire’s poem “Parisian Dream.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

Françoise Sagan, The Art of Fiction No. 15

Issue no. 14 (Autumn 1956)

I had read a lot of stories. It seemed to me impossible not to want to write one. Instead of leaving for Chile with a band of gangsters, one stays in Paris and writes a novel. That seems to me the great adventure.

In Paris and in Arcadia

By Zygmunt Haupt

Issue no. 4 (Winter 1953)

In the inside pocket of my coat, in a compartment of my much-used wallet I treasured a check for 500 francs nicely folded in four. From my looking at it so often to assure myself it was still there, the check had become a little crumpled and yellowish, but it had its full value. This check was a kind of magic passport for me, a safe guarantee of my return. It would then be a diploma, also, for title failure of my life’s dream, for my surrender in the conquering of the world…

Parisian Dream

By Charles Baudelaire

Issue no. 82 (Winter 1981)

It is a terrible terrain

no mortal eye has seen

whose image still seduces me

this morning as it fades …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2J7CwqT

Comments

Post a Comment