In his new biweekly column, Pinakothek, Luc Sante excavates and examines miscellaneous visual strata of the past.

The more empty the photograph, the more it implies horror. The void that dominates an empty photograph is the site of past human activity. It presents itself as a hole in the middle of the picture. The beds, tables, chairs, lamps are not the subject; they are the boundary. Some empty images tease the eye, suggesting clues that may dissolve upon closer examination. More often the scene is as near to a blank canvas as it can be without fading into nothingness. But then we, as habituated viewers, tend to brush a dramatic gloss upon such pictures. What we see cannot be as perfectly banal as it seems. The lighting and composition awaken unconscious memories of crime-scene photos; the drama comes from what is missing. It’s a bit like Sherlock Holmes’s dog who did not bark. What is missing is an apparent reason for the picture to have been taken.

These pictures, for the most part, do not contain human beings. They do not depict scenes that are beautiful or interesting in themselves. They do not give enough of the right kind of information to have been of use to real-estate agents. Their focus is too specific to have served in tax surveys. It is unlikely that the inhabitants of these dwellings would have taken the pictures for their own amusement. The photos do not look sufficiently professional to have been taken by the press, even assuming the press might have had reason to take an interest in random hallways or staircases. That only leaves one possibility, which is that they were taken by the police, for the purpose of securing evidence at the scene of a crime.

Over the years I have looked closely at police evidence photographs from New York, Paris, Sydney, Los Angeles, Mexico City, and some others besides. Every city seemed to have its own distinct—what? “Style” is not the word, is it? For one thing, it was unconscious, whatever that thing was. Could we call it a “fingerprint,” a “profile,” an “MO”? The available language appears loaded, but for good reason. The connection is not idle. Detectives are in the business of detecting patterns of display or behavior to which the parties themselves are oblivious. Criminal investigation is in effect an intense critique of style. Every homicide detective is as rigorous as the most exacting scholar or curator or impresario or fashion buyer or grant-panel judge, lavishing attention upon people, places, and things that would not otherwise be the object of such scrutiny. As a consequence, when we want to know how people lived, criminal investigation is uniquely suited to supply a broad range of answers, since most crime scenes are rigorously ordinary, since crime can occur anywhere, since people do not have the opportunity to clean up for company. The archived remnants of criminal investigations of the past are superior if neglected anthropological documents. But because these are also pictures, photographs, we can confer aesthetic values upon them that were never intended by anyone connected with their making; they are no less real for all of that. Like homicide detectives, we ordinary viewers learn to recognize patterns, often by intuition and without necessarily being able to name the connecting thread.

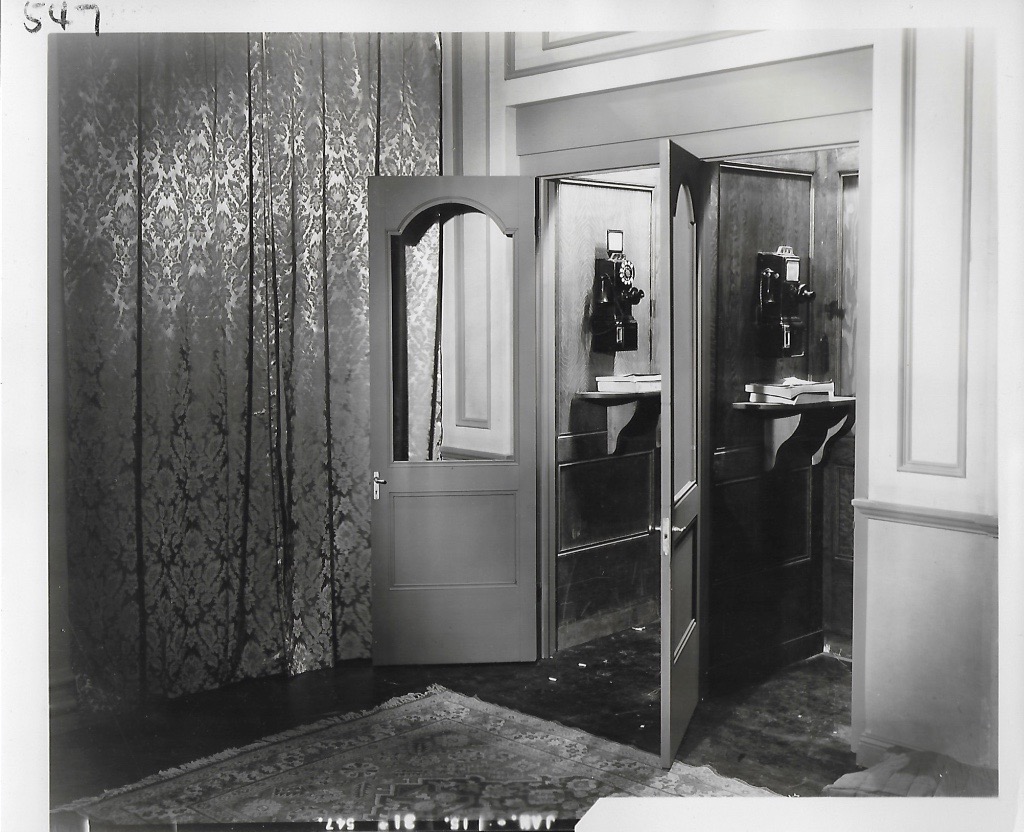

Take a look at this picture. The scene is distressed, a bit desolate, strictly insignificant. It could be a crime scene. And yet something is amiss, no? Below is another picture, from the same period, also empty, banal, unstudied. That it shows a barber shop might make the viewer remember the murder of Albert Anastasia, although that did not occur until 1957. If you look closely, though, it soon gives the game away. At top center is a large klieg light, at right is a light-diffusing black metal sheet on a pole—known in the trade as a “flag”—and at center right, in front of the mirror, is a slate with cryptic markings. The photo is a “daily,” a record made of a film set when production has struck for the day, so that it can resume the next day with continuity intact. It’s from a movie called What! No Beer? directed in 1933 by Edward Sedgwick and starring Buster Keaton and Jimmy Durante. The shot of the phone booths gives fewer clues, only the incongruous movers’ blanket almost unnoticeable at the bottom right corner and a sense of the lighting being just too refined. That one comes from the 1931 feature Men Call It Love, directed by Edgar Selwyn and featuring Adolphe Menjou and Leila Hyams. These pictures are documentary studies, strictly speaking, although what they document is confection.

The Hollywood dailies show what appear to be potential crime scenes, platonically and artisanally conceived, striking in their randomness, their ordinariness, their carefully groomed untendedness. But their mystery is twice-removed. They are not pictures shaped around a void–that of the unnamed occurrence–but flat renditions of a more summary void: a simulacrum of life. By contrast, the crime-scene photographs, taken in Brooklyn in the 1930s, are effectively spirit photographs. Those abjectly fraudulent pictures of revenants and ectoplasm absorbed ambient grief and combined it with guilt, the suppression of doubt, and the acceptance of absurdity, resulting in grotesquely volatile tableaux. The crime-scene photographs more subtly serve up a brew of any number of states: anxiety, uncertainty, boredom, stupor, rage, desire, hopelessness.

In 1929 the French writer Pierre Mac Orlan published an essay called “Elements of the Social Uncanny”–his term for a sort of metaphysical aura, or a seam between worlds, that can sometimes be found amid the ordinary grime of urban life. He illustrated the piece with an anonymous and un-captioned photograph of a bed, its sheets soaked in blood, in a room with striped wallpaper. He writes:

Here is a hotel room… The actors in the drama are no longer present. Only the blood remains, and all the thoughts it inspires, from the initial moral and physical disgust to a detailed reconstruction of the frightening set of actions that have led up to this simple image, almost indescribable but heavy with fear, with hot and greasy odors, with anxiety.

It is not an interpretation of a fact by an artist; neither is it an image that holds a mirror to reality. It is simply a truth revealed by the provisional death of the force that once gave life to that scene of carnage. Death and an equally momentary immobility reveal and highlight the alarming qualities that give this unclean and vulgar image an emotional power that works on the imagination much more clearly and profoundly than would an actual view of the room, without the mediation of the lens.

By “momentary immobility” he means the frozen moment of the photograph. He goes on to write that “it is thanks to its incomparable power to create death for a second that photography will become a great art, one that cannot simply be ranked among the visual arts but which, with singular power, finds its place among everything that constitutes the life of the mind.” His idea is that photography is a kind of soul murder, one that leaves its victim physically unharmed but entombed forever in two dimensions, like a butterfly in a case. It follows that the empty photograph, which exists to show what cannot be shown, actually contains that unshowable matter. Every photograph is imbued with an invisible array of circumstances and contingencies, frozen at the moment it was taken. These secretly operate on the viewer. We can sense in our bellies when we are looking at disturbance.

Read our Art of Nonfiction interview with Luc Sante here.

Luc Sante’s books include Low Life, Evidence, Kill All Your Darlings, and The Other Paris.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2Dng8WK

Comments

Post a Comment