We Need to Talk About the Canon: Picturing Demographics in ‘The Norton Anthology of American Literature’

In the last 20 years or so, the discussion of diversity in the American literary canon has exploded, garnering space in mainstream media outlets. A wide array of magazines, journals, and websites have tackled the issue. A 2013 New Yorker article titled “Canon Fodder: Denouncing the Classics” details the prickly and vague assumptions with which experts attempt to define canonical works. Other articles aim to deconstruct or expound upon the problem, often with similarly severe titles: “What is Literature?: In Defense of the Canon” (Harper’s, 2014); “The Literary Canon Is Still One Big Sausage Fest” (Jezebel, 2012); “Reconstructing the Canon” (Harvard Political Review, 2018), “The Canon Is Sexist, Racist, Colonialist, and Totally Gross. Yes, You Have to Read It Anyway” (Slate, 2018).

The majority of literary Americans—readers, writers, editors, publishers, professors, reviewers, and so on—are now all too aware of the serious problems surrounding literary inclusivity and representation. As a result, recent years have seen an uptick the publication and recognition of writers of more diverse backgrounds. This positive gain is due, in part, to an expanding network of organizations that support diversification, including VIDA, Lambda Literary, Cave Canem, Kundiman, and others.

But as yet, there has been very little hard data from which to discuss the extent of mis- or underrepresentation. Understandably so: such an undertaking would require a massive investment of time and resources. One manageable place to start, though, is to examine the textbook anthologies we offer American students. Indeed, these anthologies are often meant as snapshots of the canon, given to high-schoolers and undergraduates in literature survey courses nationwide. The most well-known of these is probably The Norton Anthology of American Literature.

The Norton Anthology has been a fixture in American classrooms since its introduction in 1979. This series is curated by a rotating assembly of editors, with new editions published every four to six years. W. W. Norton guards their sales figures and course adoption statistics closely, but, as of 2016, they claimed that roughly 12 million students have used The Norton Anthology of American Literature during its lifetime. It’s unclear if this figure includes resales of used books at college bookstores or reused editions in high school classrooms. Even so, this means about 4 million students per decade have used the anthology (or about 400,000 a year), on average.

This anthology series has had a foundational impact on defining what many readers and scholars would identify as an “American canon.” It follows that a demographic analysis of these books would—at the very least—yield a starting point for a more quantitative, statistical analysis of representation in the The Norton Anthology and the canon. And, like a selfie, this picture is not only a reflection of ourselves and our literary output, but a memento of who we are at this particular moment in time.

I conducted this study not for any prescriptive means, nor as any sort of definitive yardstick on the condition of American letters. At most, the findings listed here may be viewed as a measure of currently accepted levels of representation in anthologies. The central impetus for this examination was simply to contribute a data set that offers a snapshot of one version of the American canon (the version most familiar to students and teachers of literature in American high school and university classrooms).

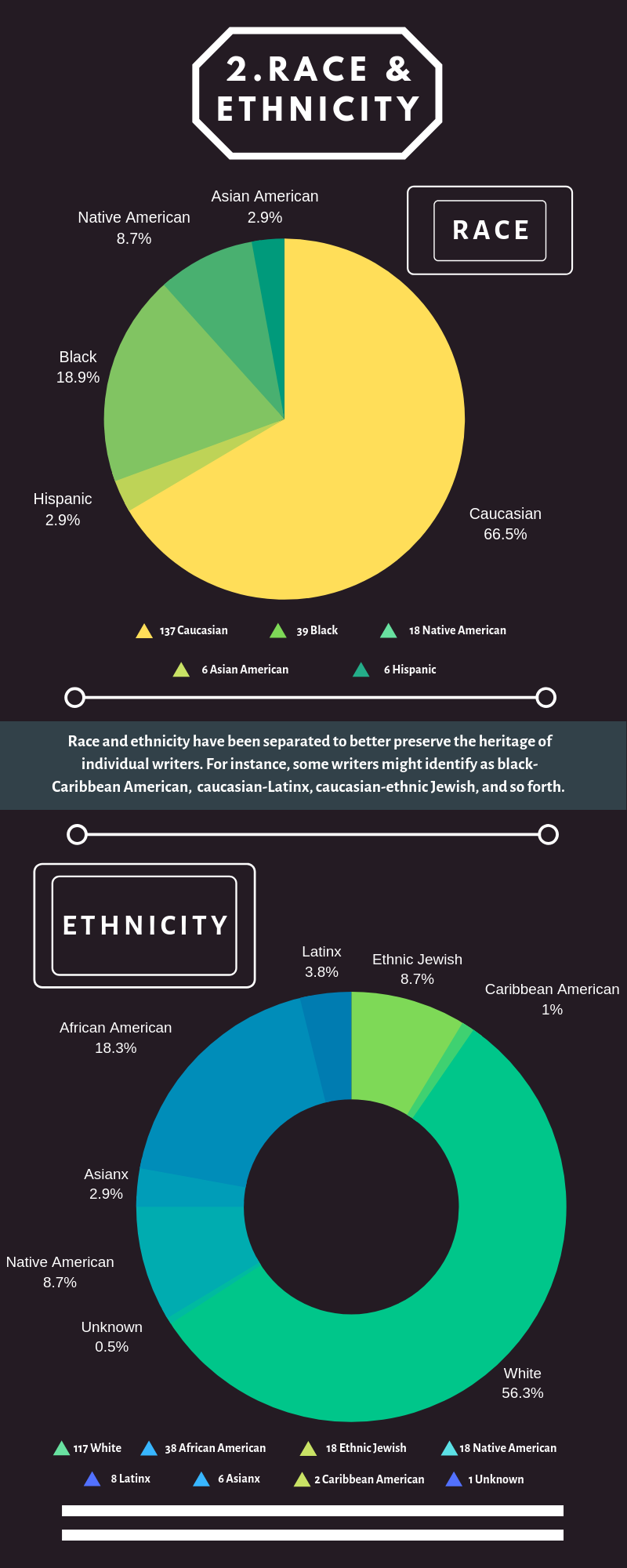

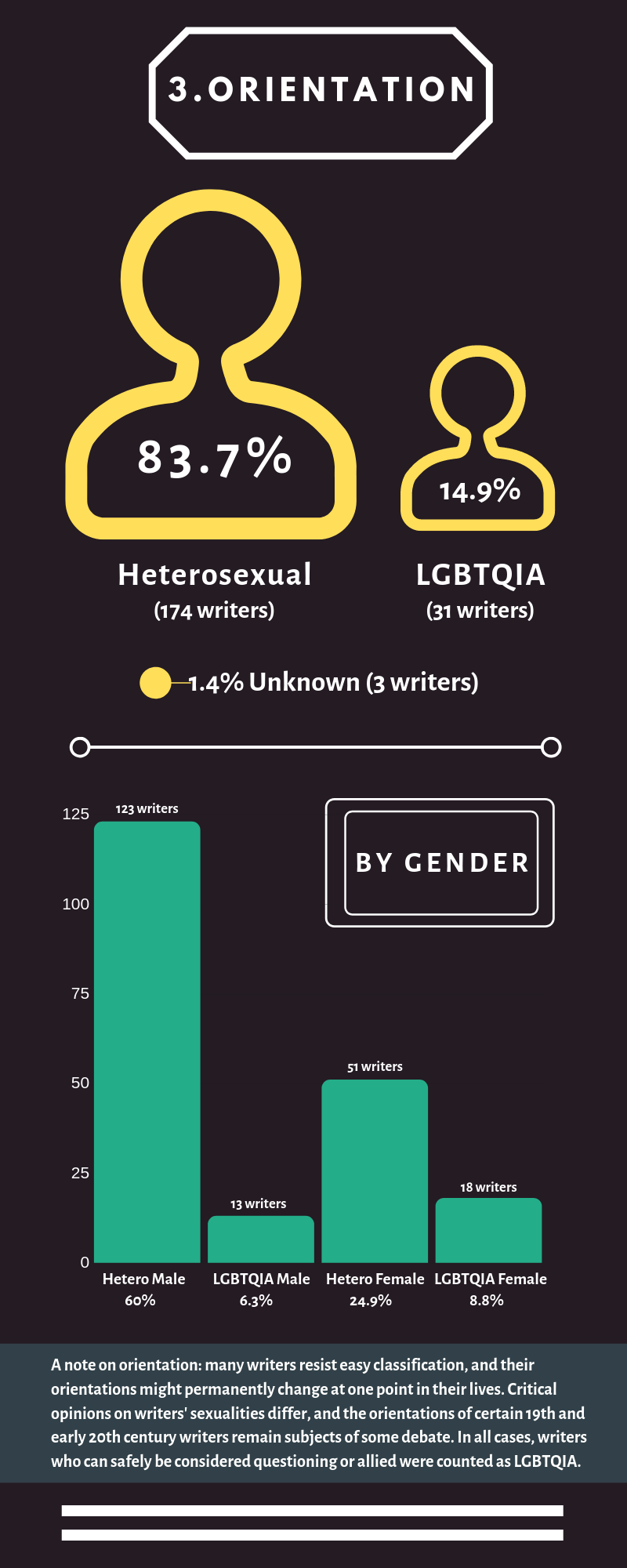

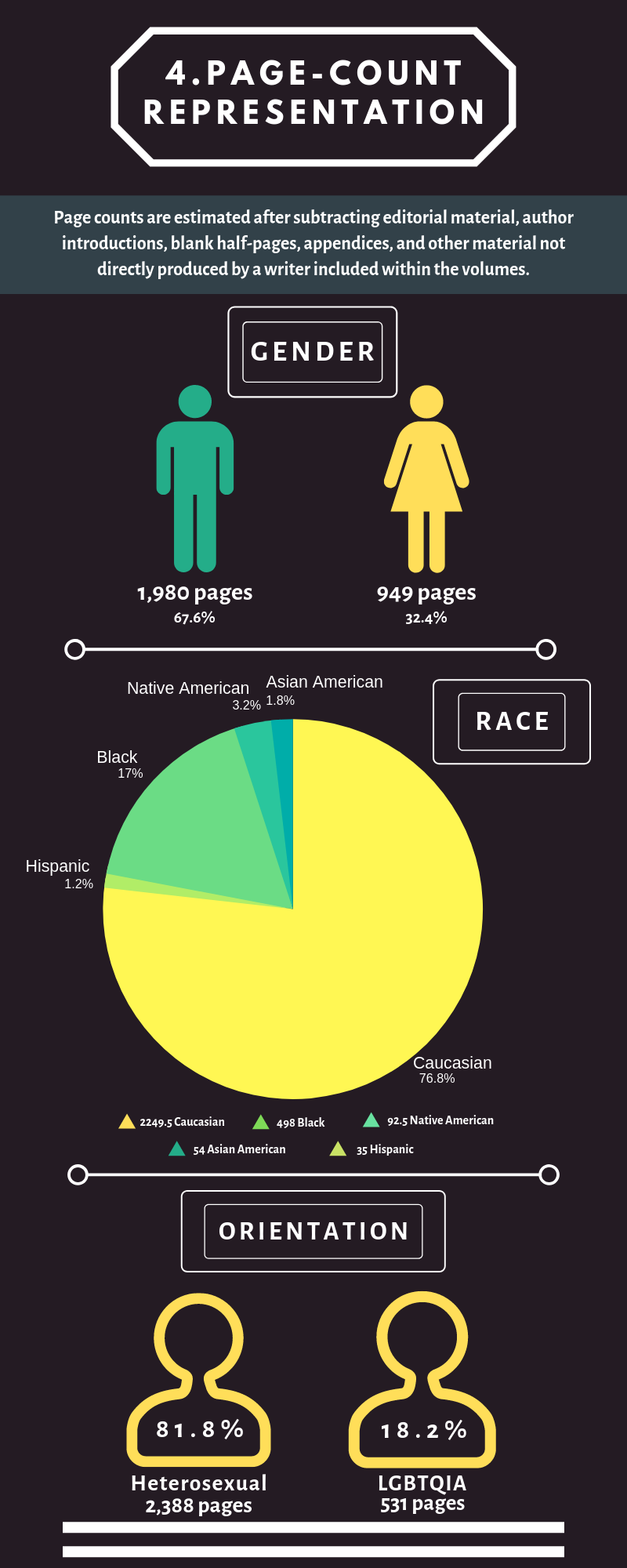

This snapshot concentrates on the 194 writers in three books of The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Ninth Edition, volumes C, D, and E (“1865 to the Present”), published in 2017. This study excludes volumes A and B (“Beginnings to 1865”). The selection of writings included in these first volumes is limited due to the oppression and erasure enacted upon minorities in antebellum America. These early books consist mainly of unattributed oral literatures, religious tracts, letters, and memoir-narratives. Simply stated, a demographic analysis of the first two books of The Norton Anthology would be largely moot; they define the underrepresentation the study seeks to explore in the anthology’s later volumes.

A final note before presenting the data: There’s a saddening byproduct to spending a significant amount of time coding and simplifying each writer down to his or her demographic information. Writers are notoriously complex people, and they frequently make very concerted efforts to subvert easy categorization. At a certain point, I began to feel as though I was doing an injustice and, indeed, a violence to the legacy of many writers. Demographic data flattens and dehumanizes its subjects in a very uncomfortable way, and I apologize to all writers and readers for reducing people who, by their very nature, are irreducible. This study was undertaken in good faith and under the auspices of exploration and learning. I welcome disagreement, discourse, and correction, particularly from experts on demographic studies and on the identities of writers contained in The Norton Anthology.

What follows are data visualizations of information compiled from biographical and critical research. The data gets much more complex and difficult to parse at its deeper, more intersectional levels, though I plan to continue with and add to this work (and welcome others to do the same). I hope these summaries provide a starting point to further statistical analyses of representation in American literature and that this information is helpful to anyone interested in our current and future trajectory toward literary diversity.

Norton provides a full table of contents of these editions online, available for perusal here.

The post We Need to Talk About the Canon: Picturing Demographics in ‘The Norton Anthology of American Literature’ appeared first on The Millions.

from The Millions http://bit.ly/2XWy1nj

Comments

Post a Comment