“We see with other eyes, we hear with other ears; and think with other thoughts than those we formerly used,” wrote Thomas Paine, author of Common Sense (1791) and The Rights of Man (1792). One of the most persuasive spokesmen for American independence, he championed the clearing away of British “cobwebs, poison and dust” from American society. American independence, he argued, could never be complete without that.

Many Americans thought the same way: that apart from economic stability and success, what they needed almost more than anything else after political independence was intellectual and cultural independence, free from the stifling influence of British arts, letters, and manners. They resented their cultural subservience, which had not disappeared with the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Yet for more than a century after the Revolution, the majority of literate and cultured Americans did not want to turn their backs on British culture, “their ancient heritage”—especially its literature and the historical traditions of its language. About seventy long years after Paine’s statement, the popular English novelist Anthony Trollope elegantly expressed this powerful, persistent, and apparently inescapable linkage: “An American will perhaps consider himself to be as little like an Englishman as he is like a Frenchman. But he reads Shakespeare through the medium of his own vernacular, and has to undergo the penance of a foreign tongue before he can understand Molière. He separates himself from England in politics and perhaps in affection; but he cannot separate himself from England in mental culture.” Janus-like, and often at less than a fully conscious level, Americans knew that their “mental culture,” whether they liked it or not, was

linked to Britain’s, and they had little taste for parting with it.

*

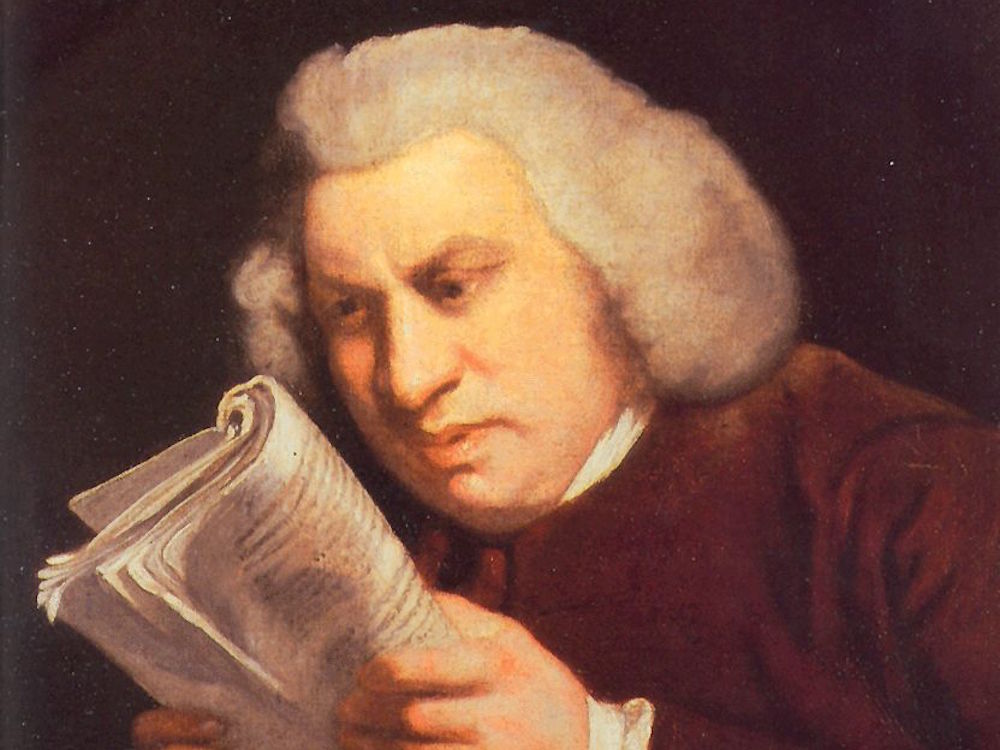

America’s lingering literary and linguistic attachment to England is nowhere so evident as in the nation’s pervasive ambivalence toward Samuel Johnson and his great dictionary, published in 1755, which many call the first major dictionary of the language. He was the great sage of English literature, brilliant essayist, moralist, poet, lexicographer, and biographer, the “Colossus of Literature” and “Literary Dictator” of the second half of eighteenth-century England, a figure thoroughly synonymous with Englishness. Throughout his career as an author, Johnson advertised his multilayered and complicated dislike of America and Americans. In 1756, the year after he published his famous dictionary, he coined the term “American dialect” to mean “a tract [trace] of corruption to which every language widely diffused must always be exposed.” He had in mind an undisciplined and barbarous uncouthness of speech. With typical hyperbole on the subject of Americans, he once remarked, “I am willing to love all mankind, except an American … rascals—robbers—pirates.”

Yet Americans could not get enough of him. They devoured his books, which libraries held in great numbers. His influence on American thought and language was vast. Thomas Jefferson recognized this as a grave problem: he wanted to get Johnson off the backs of Americans. In a letter in 1813 to his friend the grammarian John Waldo, he took note of Johnson’s Dictionary as a specific drag on the country’s cultural growth: “employing its [own] materials,” America could rise to literary and linguistic preeminence, but “not indeed by holding fast to Johnson’s Dictionary; not by raising a hue and cry against every word he has not licensed; but by encouraging and welcoming new compositions of its elements.” And yet, as one historian writes, “It was to prove more difficult to declare independence from Johnson than it had been to reject George III.” The weight of Johnson’s authority on culture in America was a legacy, both positive and negative, that would loom large in the American psyche far into the nineteenth century. Several of the leading American authors at the time actually fed the appetite for Johnson rather than attempted to dampen it. One of them, Nathaniel Hawthorne, revered Johnson. Although he complained in Mosses from an Old Manse (1845), “How slowly our [own] literature grows up,” for him Johnson could do no wrong. In London during the 1850s on government business, he recorded in his English Note-Books walking in Johnson’s footsteps—taking a meal at Johnson’s favorite London tavern, the Mitre; traveling up to Lichfield in Staffordshire to pay homage to the great man’s birthplace; and exploring Johnson’s rooms at No. 1 Inner Temple Lane in London, where his imagination luxuriated in the sense of place: “I not only looked in, but went up the first flight, of some broad, well-worn stairs, passing my hand over a heavy, ancient, broken balustrade, on which, no doubt, Johnson’s hand had often rested … Before lunch, I had gone into Bolt Court, where he died.” As for James Fenimore Cooper, he was liberally using Johnson’s dictionary as his principal authority on the language, even after America’s first large (unabridged) dictionary was published by Noah Webster.

This type of American adulation of Johnson persisted into the second half of the century. Herman Melville, in Moby-Dick (1851), the novel he dedicated to Hawthorne, has his narrator, Ishmael, remark that in his telling of the story he had “invariably used a huge quarto edition of Johnson [his dictionary], expressly purchased for that purpose; because that famous lexicographer’s uncommon personal bulk more fitted him to compile a lexicon to be used by a whale author like me.” Louisa May Alcott, in her American classic Little Women (1868–69), features Johnson’s Rasselas and his book of essays, The Rambler, in a memorable scene or two. Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens), however, was not so positive about Johnson, bearing witness to this Johnsonian obsession even as he debunked it. He had a go at Johnson at the expense of American Johnson lovers when he toured London only a few years before the outbreak of World War I. One day at the Cheshire Cheese tavern, near which Johnson had lived and where, legend has had it, he spent a good deal of time, Twain was enjoying some refreshment in the “Doctor Johnson room” with Bram Stoker, author of Dracula, and the American journalist Eugene Field, when he burst out: “Look at those fools going to pieces over old Doc Johnson—call themselves Americans and lick-spittle the toady who grabbed a pension from the German King of England that hated Americans, tried to flog us into obedience and called George Washington traitor and scoundrel.” One could understand the adulation of Johnson by the English, he continued, “but of our own people, coming to the Cheese, ninety-nine per cent do so because they don’t know the man, and the others because they feel tickled to honor a writer a hundred and fifty years or so after he is good and rotten.” For the rest of his time at the inn, in protest against his fellow Americans, he kept up his “slaughter of Johnson.” As for himself, he boasted he never read Johnson, “never a written word.”

*

An avalanche of British attacks on American society and culture in general and language and literature in particular in the early nineteenth century did not improve American self-confidence. While such British offensives did not exist in isolation from larger political events at the time that contributed to a hostility between the two countries, which eventually ignited in the War of 1812, that larger context fails to account for the harshness and frequency with which British writers insulted American life and manners. Many British travelers’ attacks in books and the British press were simply outrageous and in poor taste, ill-informed or not informed at all, aiming to appeal sensationally to a portion of the British reading public that was either ignorant of America and prepared to think the worst of it, or welcomed such attacks as exotic and improbable adventure stories.

Fanny Trollope, mother of the novelist Anthony Trollope, wrote a sensational best seller, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), based on her months of traveling all over the country. An engaging but also wounding account, often insightful and sometimes appreciative, it is marred by a recurring strain of anti-Americanism. As she sees it, the abuse of the language was no small part of Americans’ lack of discipline and bad taste and manners. She shudders over what she saw and heard as the vulgarity of American manners and language, appalled at the “strange uncouth phrases and pronunciation.” She is short on examples, but in an appendix she added to the fifth edition of her book seven years later in 1839, she records some family conversation in an unspecified part of the country. It contains this specimen of a father’s pride in the chickens the family is about to serve up for guests: “Bean’t they little beauties? hardly bigger than humming birds; a dollar seventy five for they. Three fips for the hominy, a levy for the squash, and a quarter for the limes; inyons a fip, carolines a levy, green cobs ditto.” She links the speech she heard to the prevalent lack of refinement resulting from the low esteem in which women were held. If America was ever going to rescue itself from this revolting social malaise, she writes, it would have to be through the refinements of the arts: “Let America give a fair portion of her attention to the arts and the graces that embellish life, and I will make her another visit, and write another book as unlike this as possible.”

In those early years of nationhood, Americans only occasionally protested. If you feel insecure, you are not apt boldly to fire back at your critics. The now forgotten Philadelphia scholar and diplomat Robert Walsh, whom Jefferson once described as “one of the two best writers in America,” did protest in “An Appeal from the Judgements of Great Britain Respecting the United States of America” (1818), but he managed simply to reinforce the persistent British belief that Americans were vain and supersensitive to criticism, “cherishing imaginary wrongs.” The shocks to American confidence and self-respect, however, being dished out by these British travelers, commentators, reviewers, and authors eventually proved to be too much for Washington Irving. They drove him to write a nine-page essay, “English Writers on America” (1819), in which he aims to stir up Americans to believe in themselves:

I shall not … dwell on this irksome and hackneyed topic; nor should I have adverted to it, but for the undue interest apparently taken in it by my countrymen, and certain injurious effects which I apprehended it might produce upon the national feeling. We attach too much consequence to these attacks. They cannot do us any essential injury. The tissue of misrepresentations attempted to be woven around us, are like cobwebs woven around the limbs of an infant giant. Our country continually outgrows them. One falsehood after another falls off of itself. We have but to live on, and every day we live a whole volume of refutation.

If the English persist with their “prejudicial accounts,” they will succeed only in “instilling anger and resentment within the bosom of a youthful nation.”

Looking back at a century of such British mockery, the historian Allan Nevins in 1923 conveyed the seriousness of the threat relentless British mockery posed to the American psyche in the first quarter of the nineteenth century and the anxiety it stirred up in the young country: “The nervous interest of Americans in the impressions formed of them by visiting Europeans and their sensitiveness to British criticism in especial, were long regarded as constituting a salient national trait.” Henry Cabot Lodge, U.S. senator from Massachusetts, was appalled by the effect on American authors: “The first step of an American entering upon a literary career was to pretend to be an Englishman in order that he might win the approval, not of Englishmen, but of his own countrymen.” American poet, journalist, and commentator H. L. Mencken, in his linguistically patriotic book The American Language (first published in 1919), provides another retrospective in sections titled “The English Attack” and “American Barbarisms.” He describes the clash as “hair-raising,” an “unholy war” of words. Captain Thomas Hamilton, a Scot, mentions a few of the prevalent barbarisms: “The word does is split into two syllables, and pronounced do-es. Where, for some incomprehensible reason, is converted into whare, there into thare; and I remember, on mentioning to an acquaintance that I had called on a gentleman of taste in the arts, he asked, ‘Whether he shew (showed) me his pictures.’ Such words as oratory and dilatory, are pronounced with the penult syllable, long and accented; missionary becomes missionairy, angel, ângel, danger, dânger, &c.”

*

With considerable zeal, the British assault on American values, manners, and achievements also turned to the state of literature in the republic. In 1810, the Edinburgh Review was severe: “Liberty and competition have as yet done nothing to stimulate literary genius in these republican states … In short, federal America has done nothing, either to extend, diversify, or embellish the sphere of human knowledge.” Again in the Edinburgh Review, Sydney Smith, founder and first editor of that magazine, whose brilliant and witty essays and reviews particularly injured American pride, mischievously asked in 1820, “Why should the Americans write books, when a six week’s passage brings them in our own tongue, our sense, science and genius, in bales and hogsheads?” Harriet Martineau, while pleased by America’s lack of “aristocratic insolence,” wrote bitingly in Society in America after her travels in America in 1836, “If the national mind of America be judged of by its legislation, it is of a very high order,” but “if the American nation be judged by its literature, it may be pronounced to have no mind at all.”

The American literati chimed in with vigor. John Pickering, the Harvard-educated diplomat and American jurist and linguist, admitted in 1816, “In this country we can hardly be said to have any authors by profession.” In his book The Importance and Means of a National Literature (1830), William Ellery Channing, the famous Unitarian minister and early Transcendentalist, declared that what he meant by a national literature was “the expression of a nation’s mind in writing,” and he called for America’s literary mind to awaken. America needed “a high intellectual culture” that paid more attention to the spirit than to material aggrandizement: “There is among us much superficial knowledge … There is nowhere … an accumulation of literary atmosphere.” More than half a century after independence, America still relied “for intellectual excitement and enjoyment on foreign minds, nor is our mind felt abroad.”

American literature did rise, however, sooner perhaps than Jefferson had envisioned. James Fenimore Cooper, Washington Irving, William Cullen Bryant, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, to mention but a few writers, all made names for themselves by the 1840s and 1850s as creative artists to be reckoned with not only in America but also in England and throughout the Continent. Emerson, the prophet-poet who strove “to extract the tape-worm of Europe from America’s body,” knew the American “renaissance” was dawning. “We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe,” he declares in his pamphlet The American Scholar (1837), which was delivered and first published under the title An Oration, Delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society, at Cambridge, August 31, 1837. In his essay “Nature” (1836), he writes, “The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us and not the history of theirs?” The speech secured Emerson’s fame.

Peter Martin is the author of numerous books, including the acclaimed biographies Samuel Johnson and A Life of James Boswell. He has taught English literature in the United States and England and divides his time between Spain and West Sussex, England.

Excerpted from The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight over the English Language, by Peter Martin. Copyright © 2019 by Peter Martin. Published by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2HKNVfa

Comments

Post a Comment