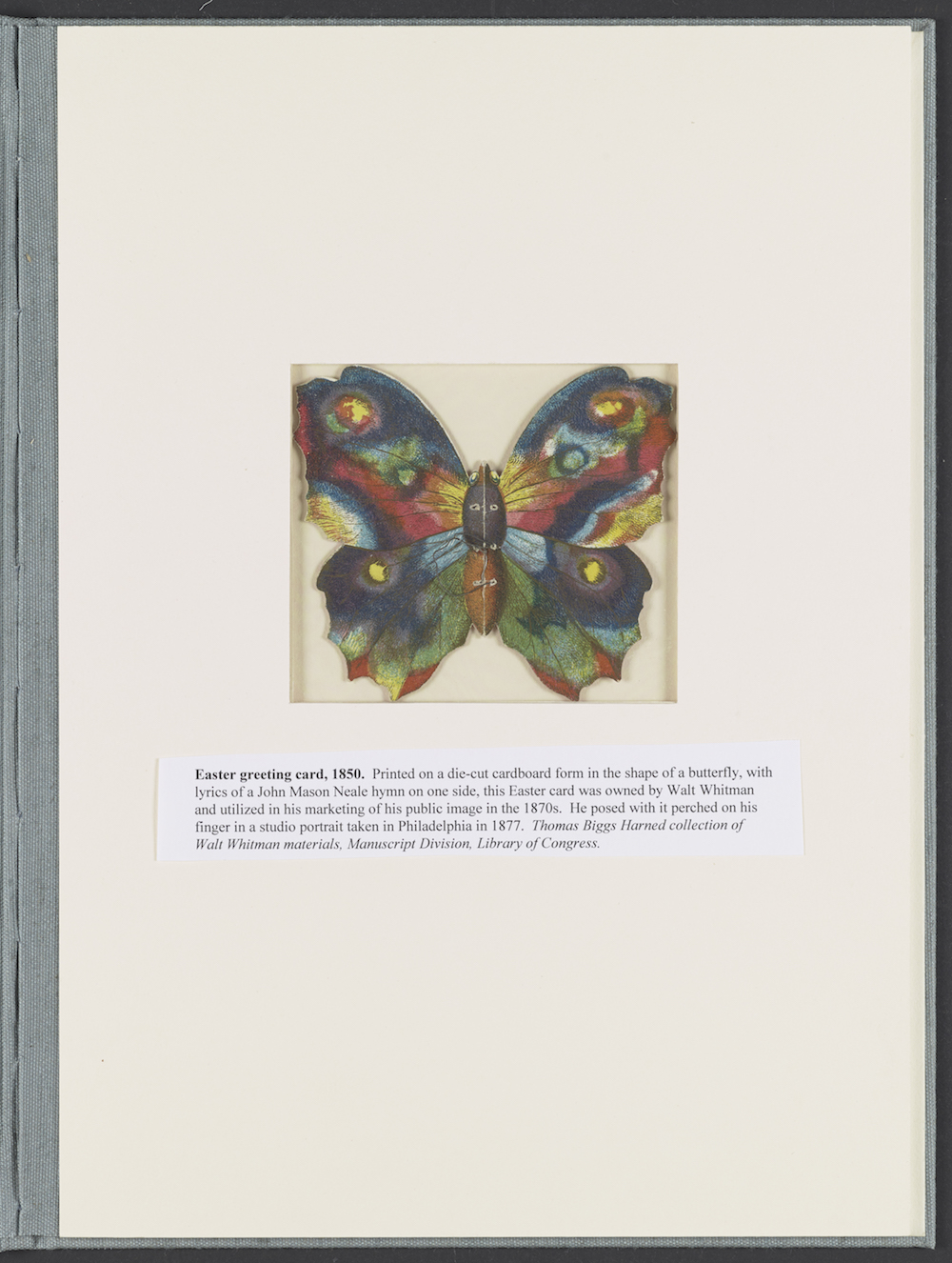

The great Walt Whitman sang a song of himself, and that song has continued to resonate over the two centuries that have passed since his birth. As a poet, a queer icon, and a literary celebrity, his influence on the American consciousness was monumental. A new exhibition at The Morgan Library and Museum, “Walt Whitman: Bard of Democracy” (on view from June 7 to September 15), examines how thoroughly Whitman’s work is threaded into this country’s DNA and mythology. A selection of artifacts from the show—including a plaster cast of the poet’s right hand, a notebook containing early versions of lines from Leaves of Grass, and the cardboard butterfly he posed with in one of his infamous author portraits—appears below.

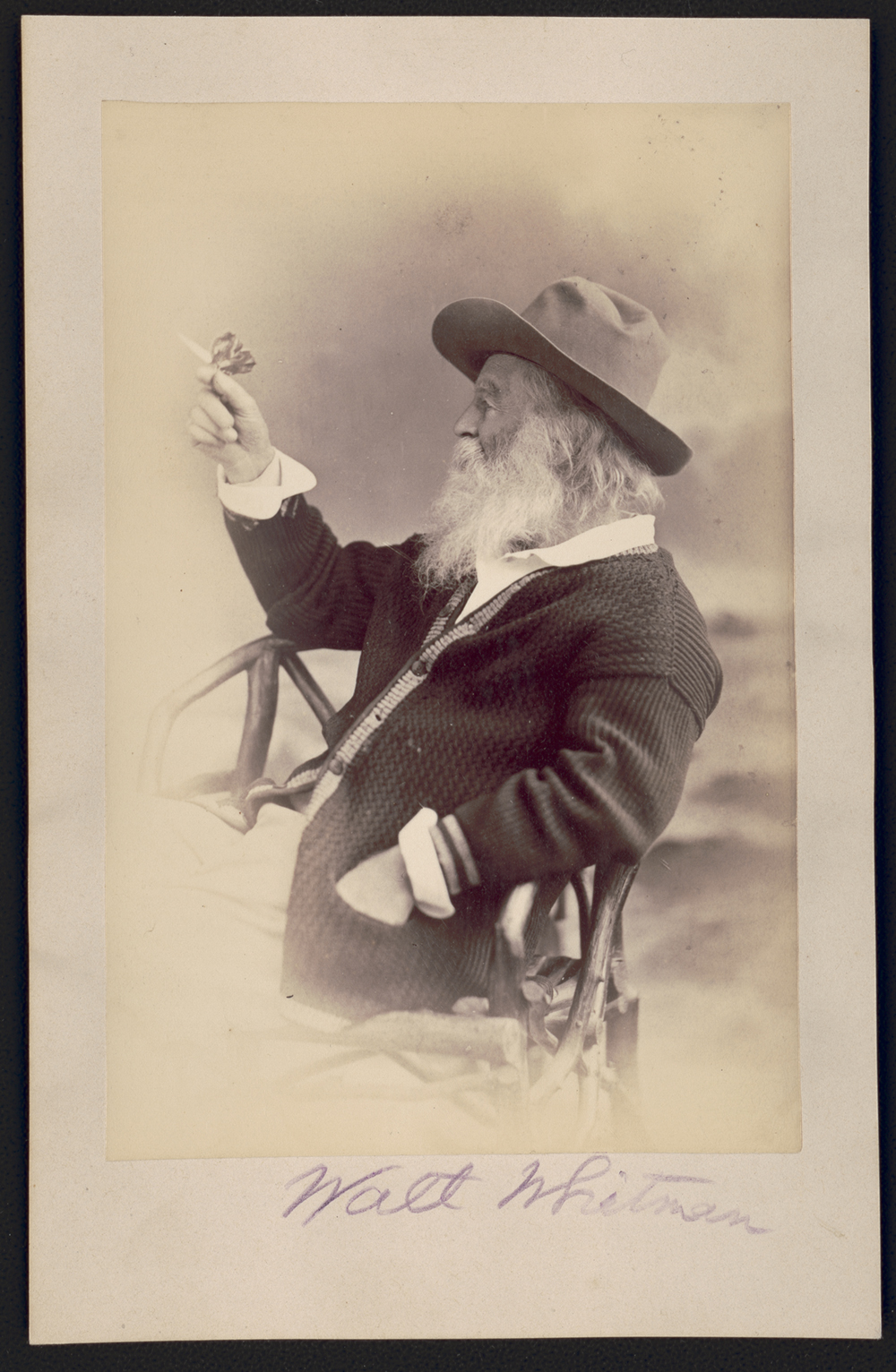

Phillips & Taylor, Photograph of Walt Whitman, 1873. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Walt Whitman’s cardboard butterfly, 1850. Manuscript Division, Thomas Biggs Harned Collection of Walt Whitman Papers, Library of Congress. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Truman Howe Bartlett (1835–1922), Plaster cast of Walt Whitman’s hand, 1881. Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Charles E. Feinberg Collection of Walt Whitman Papers.

Joseph Pennell (1857–1926), Walt Whitman’s house, Camden, New Jersey, ca. 1924, etching. Purchased on the Edwin V. Erbe, Jr. Acquisitions Fund, The Morgan Library & Museum. Photography by Graham S Haber 2019.

Moses P. Rice and Sons?, Walt Whitman and his rebel soldier friend Pete Doyle, 1865, photograph; albumen print on card mount. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

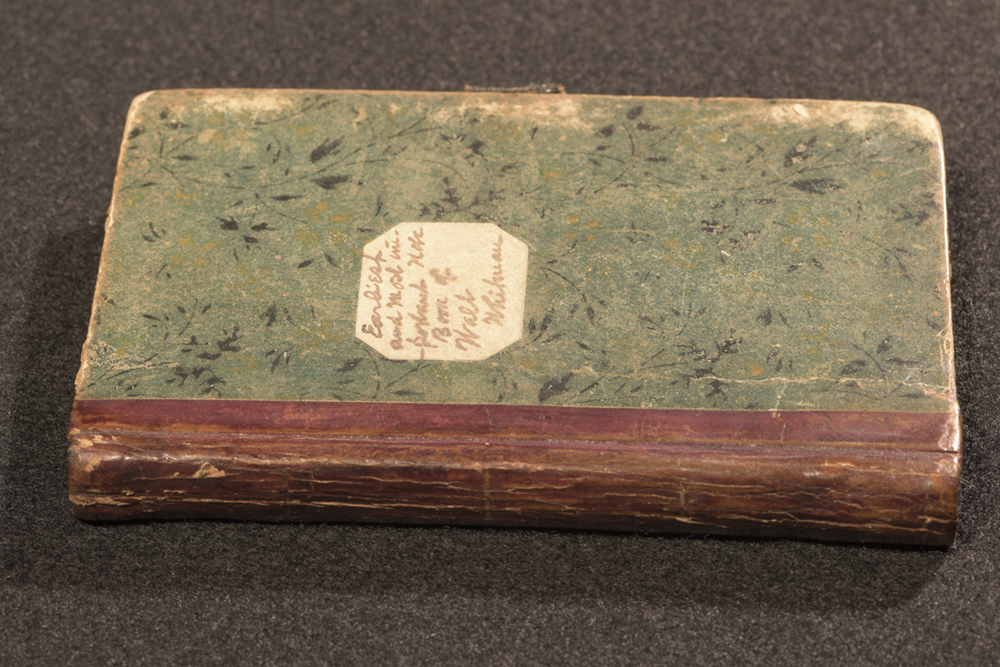

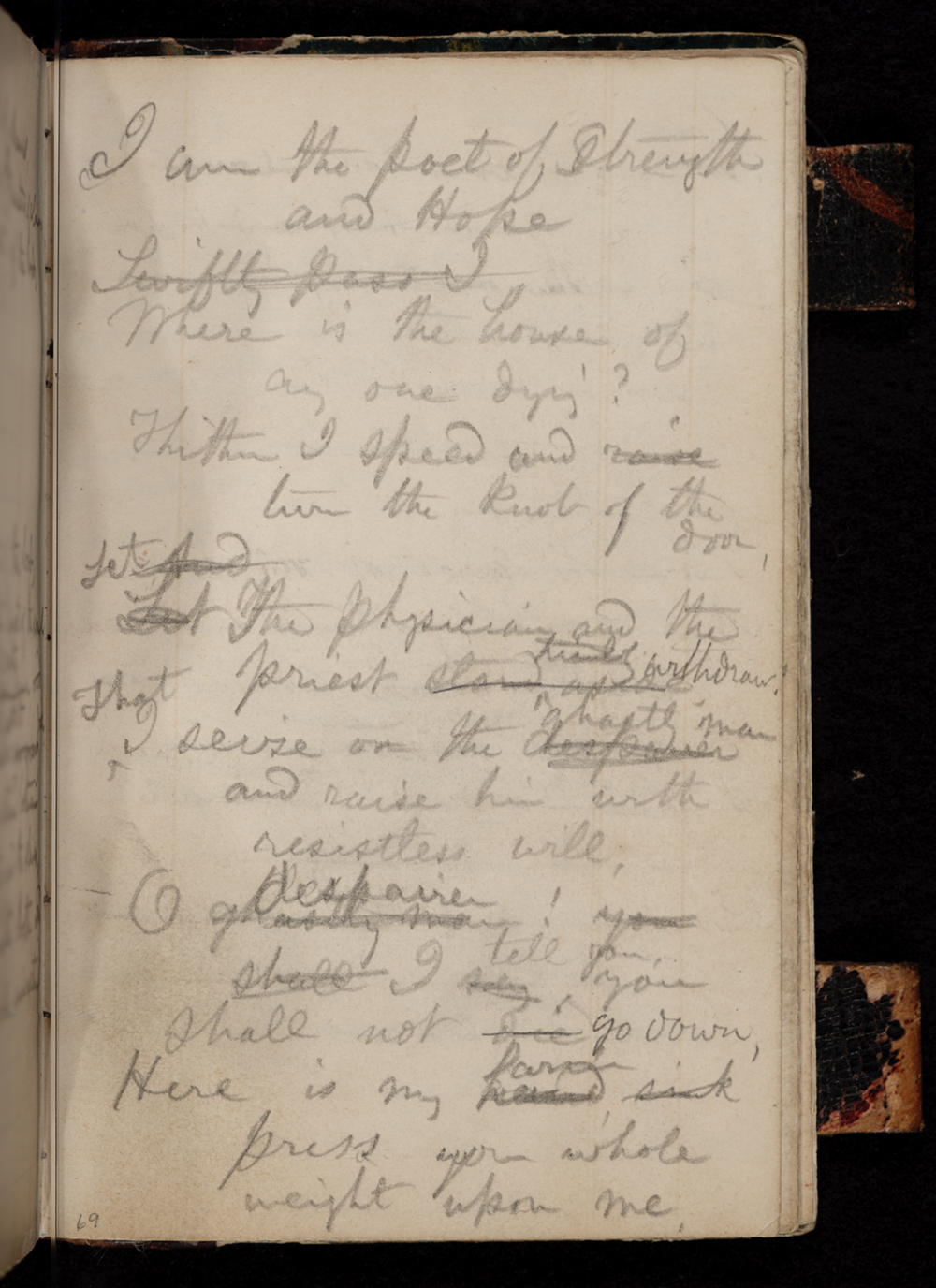

Walt Whitman (1819–1892), Notebook with trial lines for Leaves of Grass, ca. 1847-1854. The Library of Congress. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Walt Whitman (1819–1892), Notebook with trial lines for Leaves of Grass, ca. 1847-1854. The Library of Congress. Image provided courtesy of the Library of Congress.

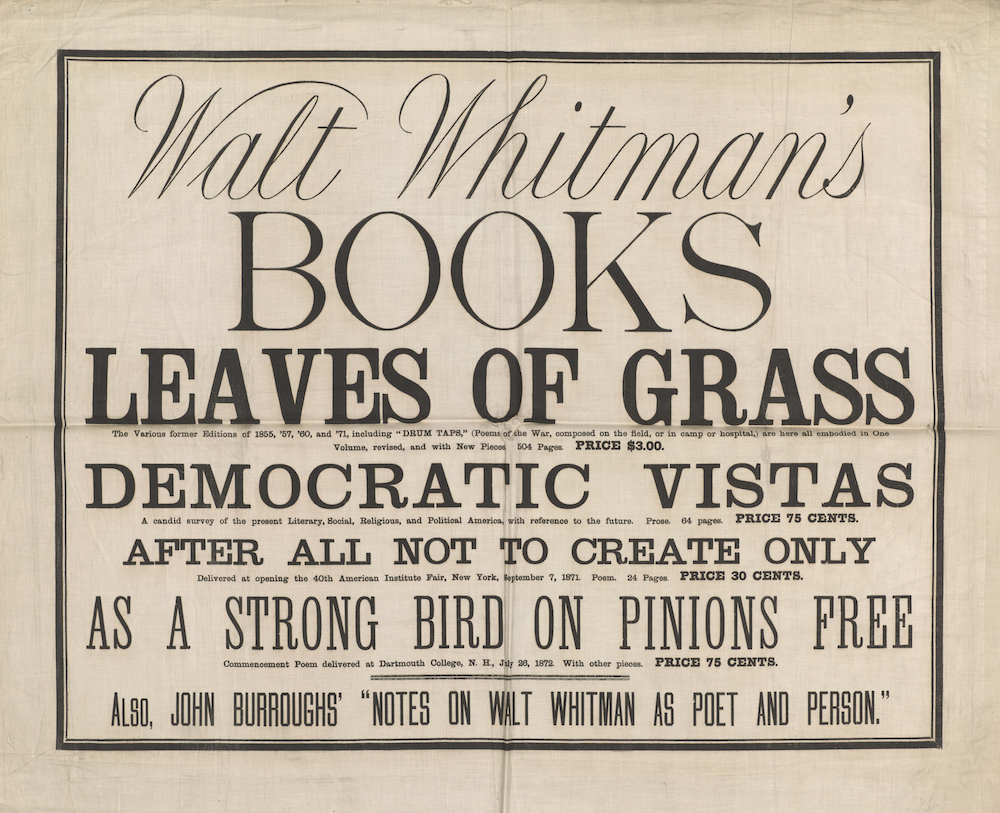

Walt Whitman, Walt Whitman’s Books, broadside advertisement printed on linen, ca. 1871. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of Charles

E. Feinberg, 1959; PML 50638. Photography by Graham S Haber 2017.

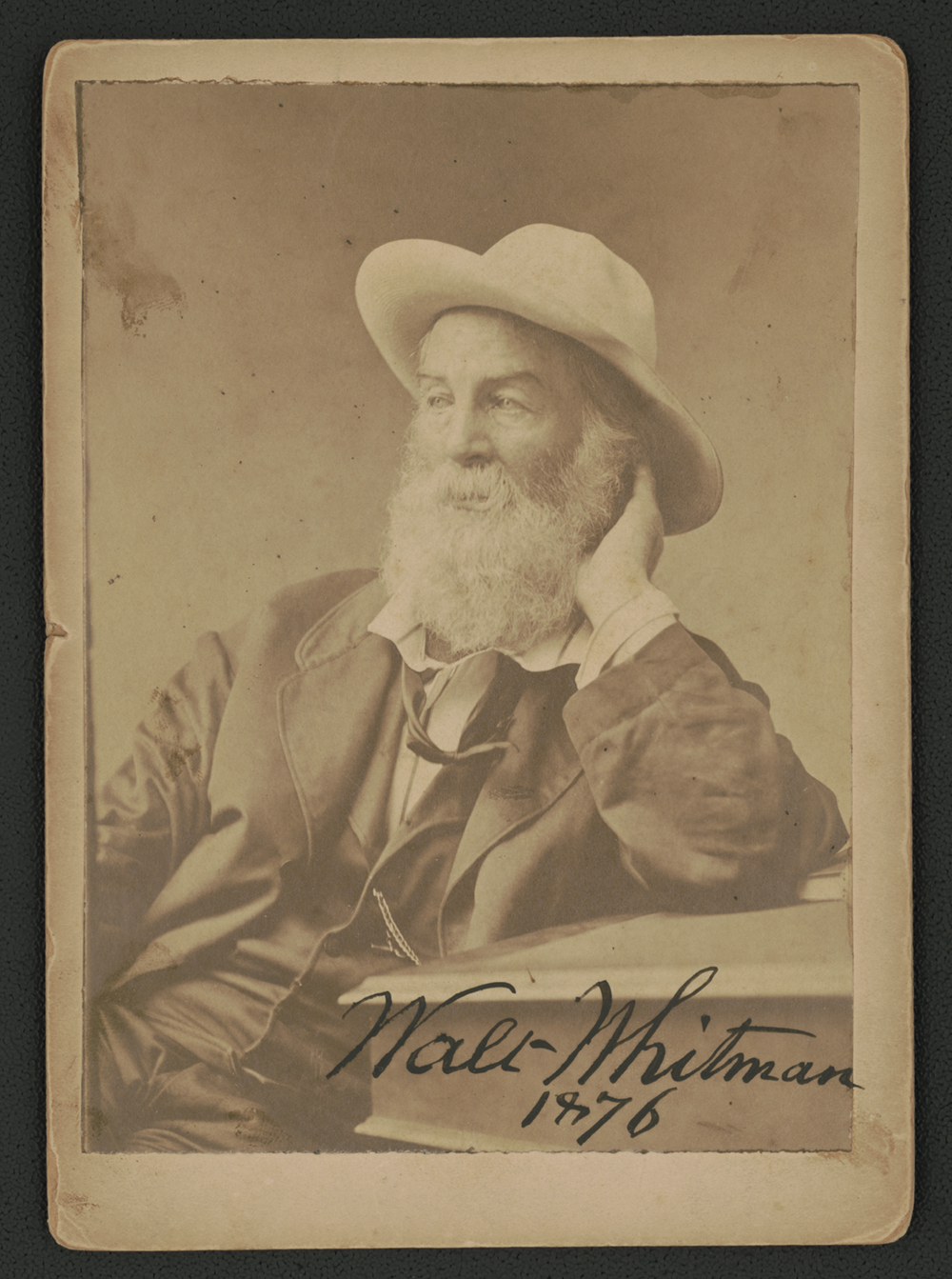

George Frank E. Pearsall (1841–1931), Walt Whitman, 1871, photographic print. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Walt Whitman: Bard of Democracy” will open at The Morgan Library and Museum on June 7.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2EMIIBT

Comments

Post a Comment