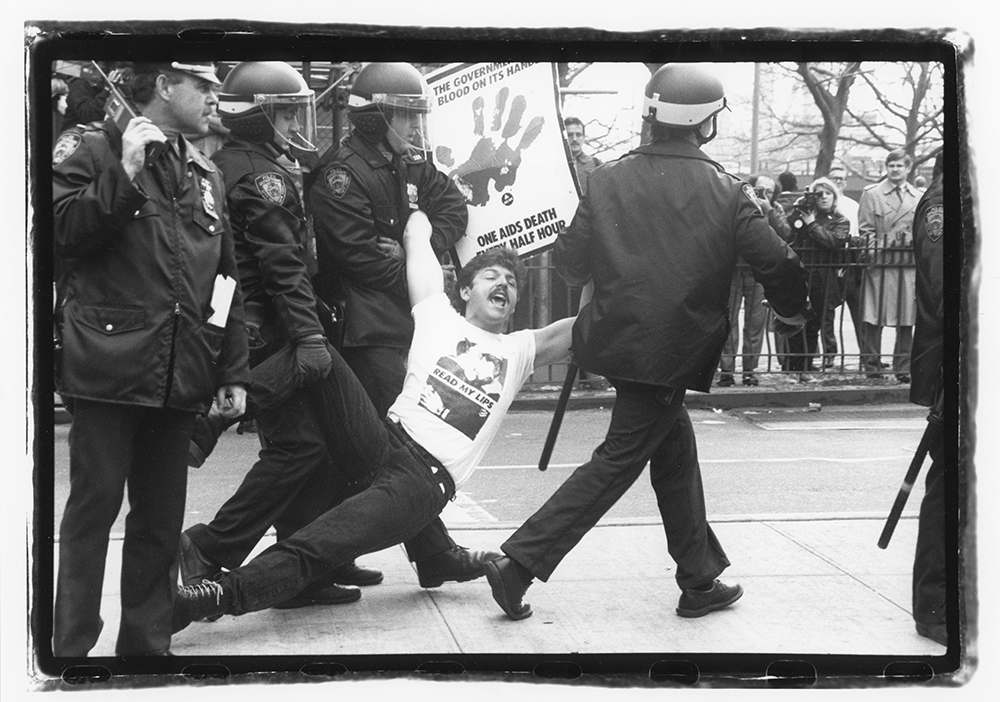

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, a flash point in the struggle for queer and trans rights. To commemorate the occasion, OR Books has reissued Fred W. McDarrah’s long-out-of-print Pride: Photographs after Stonewall, an essential collection of images by the Village Voice’s first staff photographer and picture editor. In McDarrah’s work, we see the nascent stages of a movement that’s still making strides to this day. There is pain—an Act-Up demonstrator getting dragged away by cops in riot gear—but also triumph and joy: men kissing in Central Park, silhouettes slinking toward waterfront bars, the Gay Men’s Chorus singing, smiling, looking dashing in their matching tuxedos. A selection of McDarrah’s photos appears below.

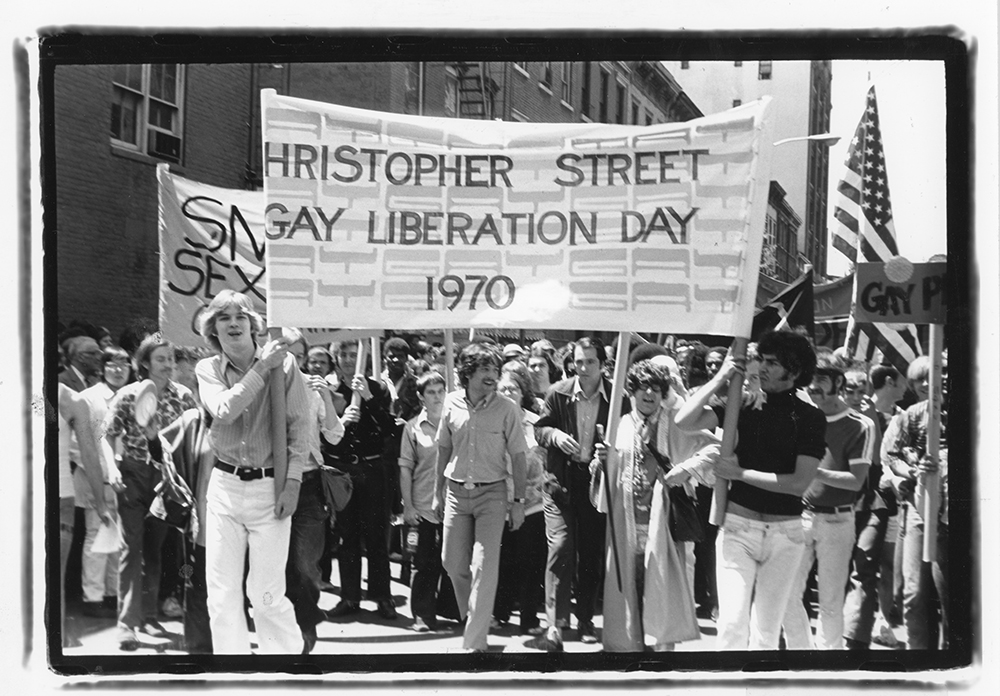

The first Stonewall anniversary march, held on June 28, 1970, was organized by the Christopher Street Liberation Day Committee, led by Foster Gunnison and Craig Rodwell. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

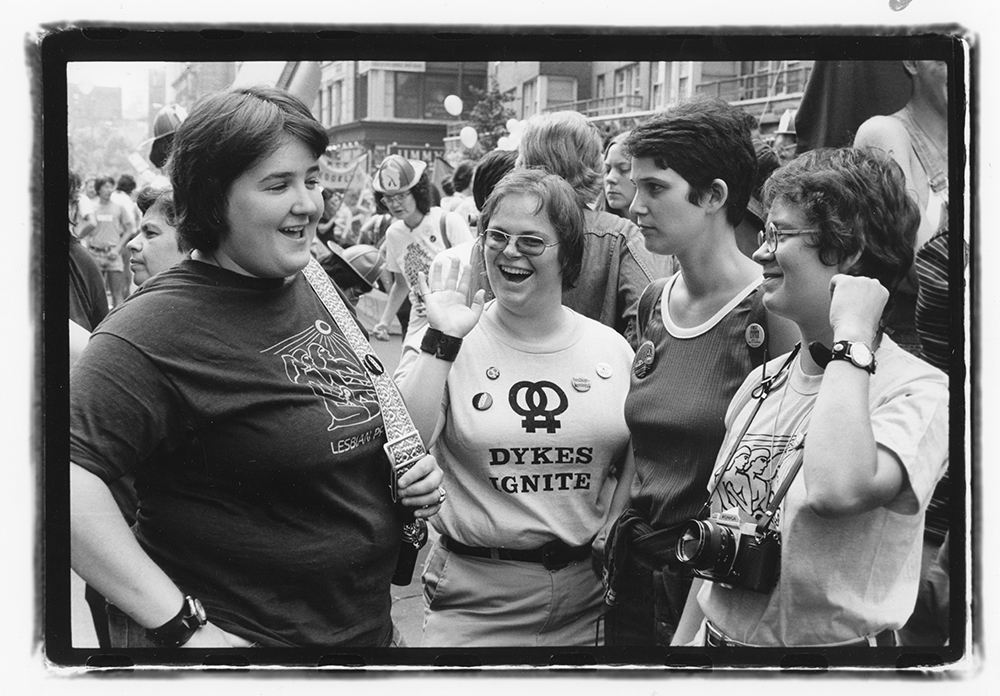

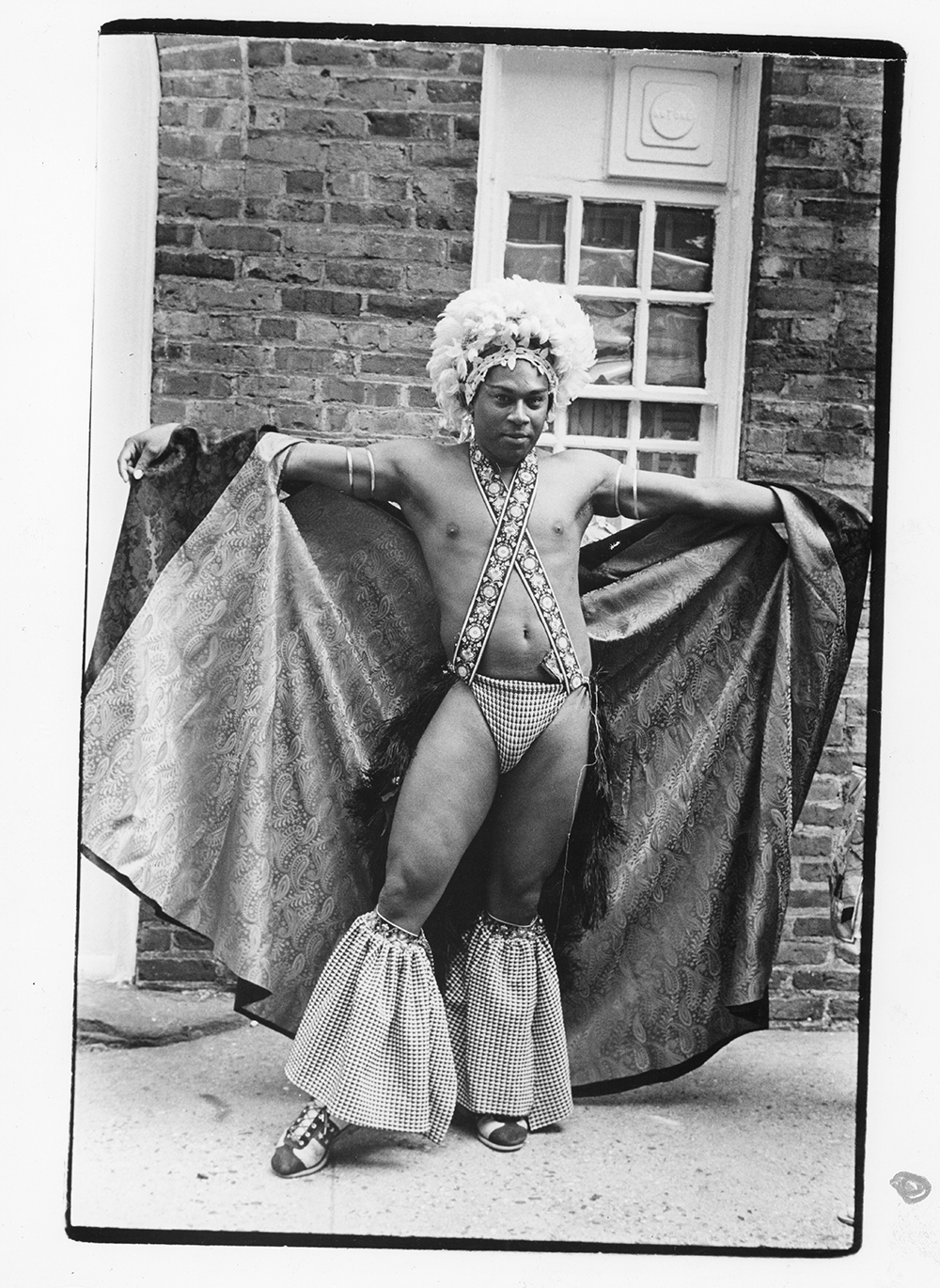

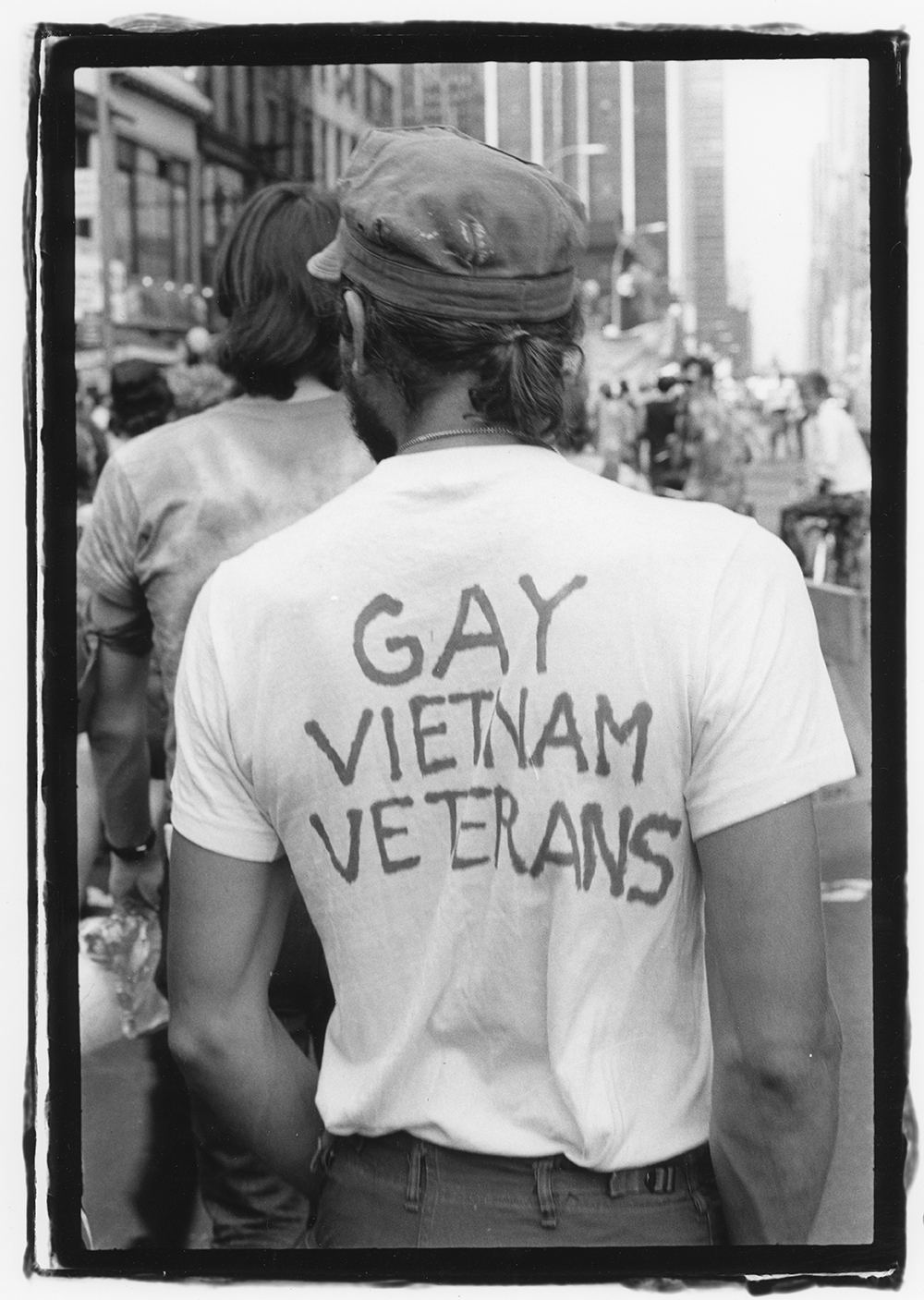

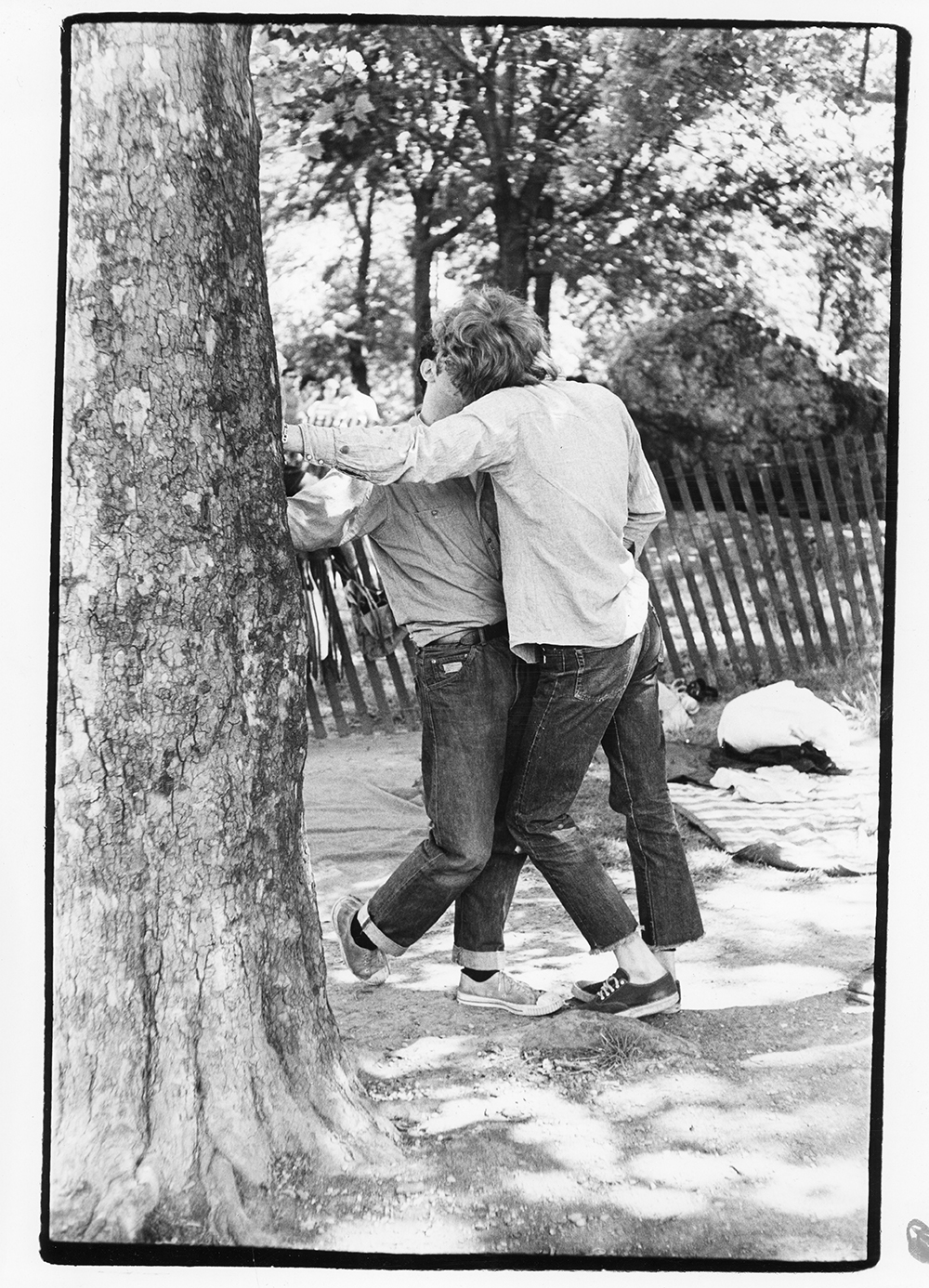

June 29, 1975. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

June 29, 1975. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

Act-Up demonstrating at City Hall for AIDS housing and counseling, drug treatment facilities, and children’s centers, March 28, 1989. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

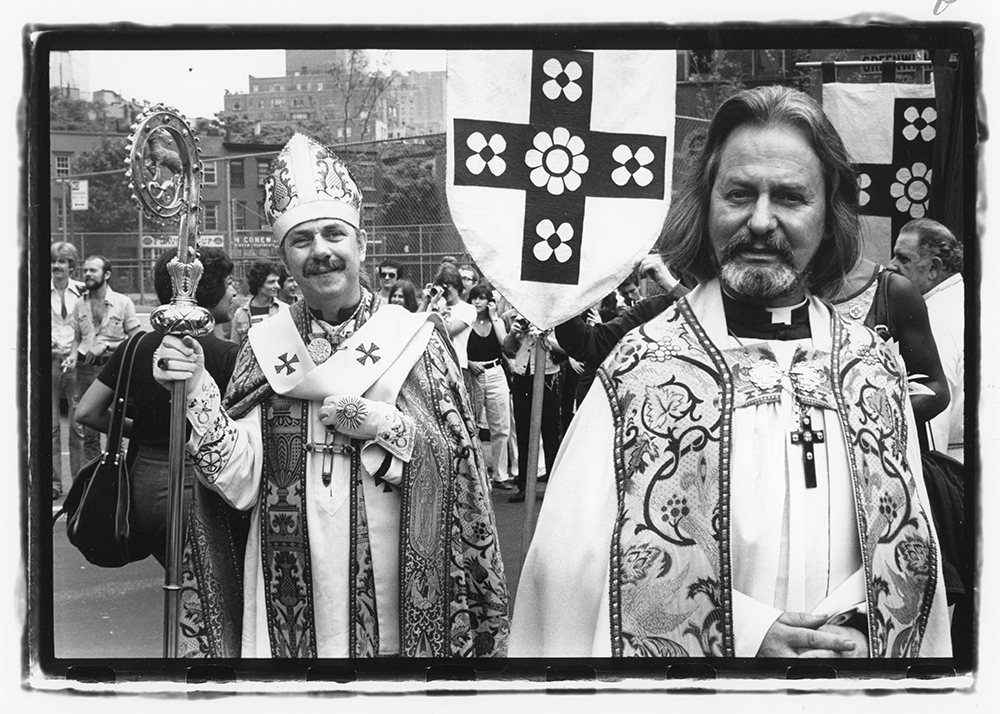

John Noble and Bishop Robert Clement, leaders of the world’s first gay church, The Church of the Beloved Disciple, June 29, 1975. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

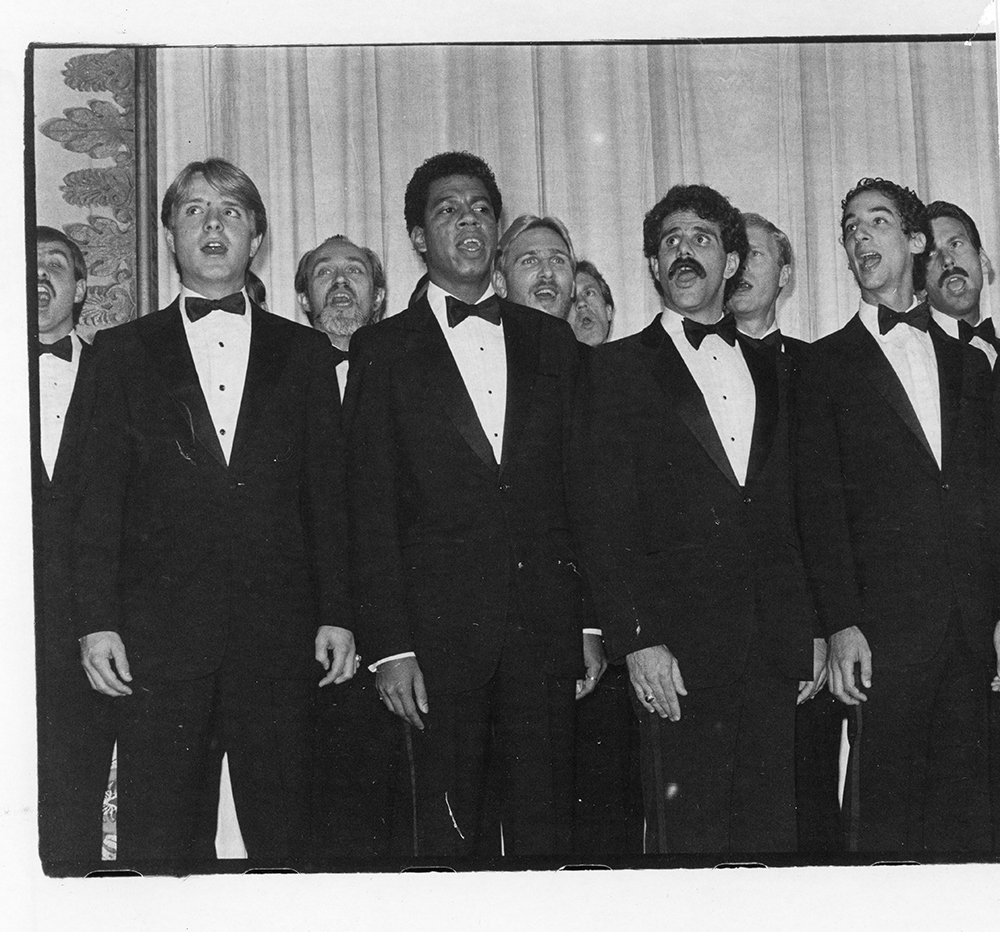

The Gay Men’s Chorus, September 27, 1982. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

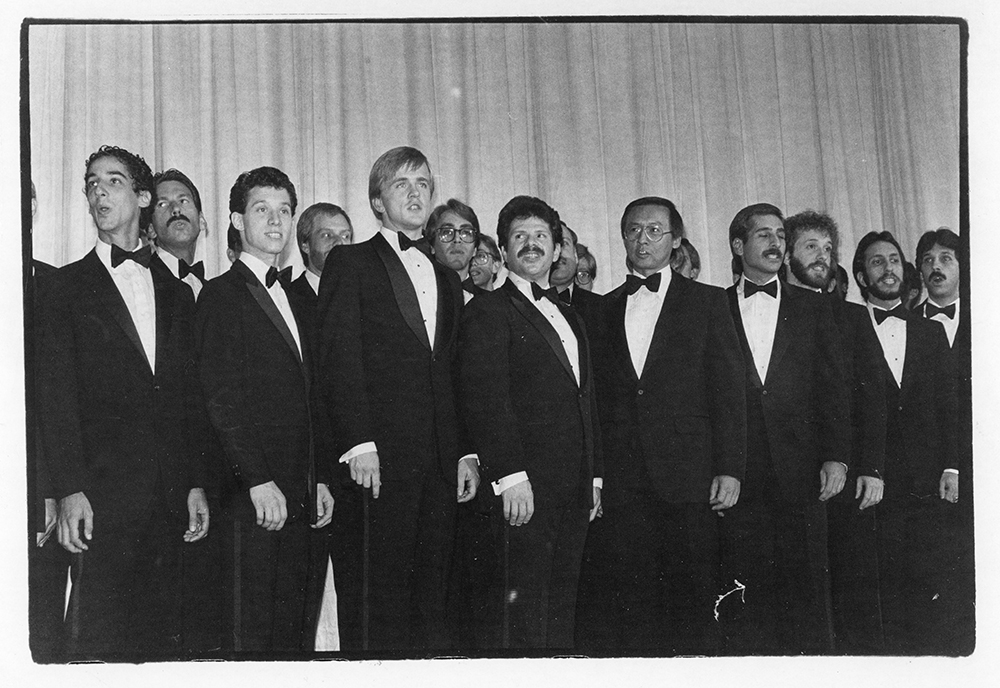

The Gay Men’s Chorus, September 27, 1982. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

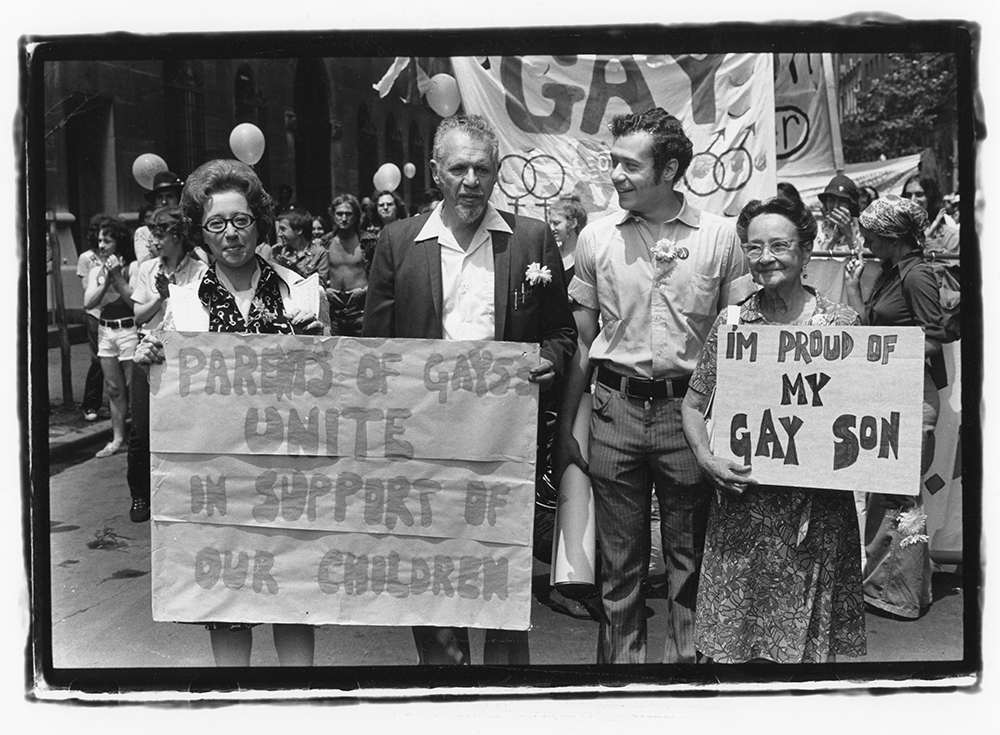

Jeanne and Jules Manford march with their son Morty, along with Sarah Montgomery, June 24, 1973. According to the public relations executive Ethan Geto, a year earlier Morty was beaten at an annual dinner for New York press by the fireman’s union chief because he was handing out pro-gay leaflets. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

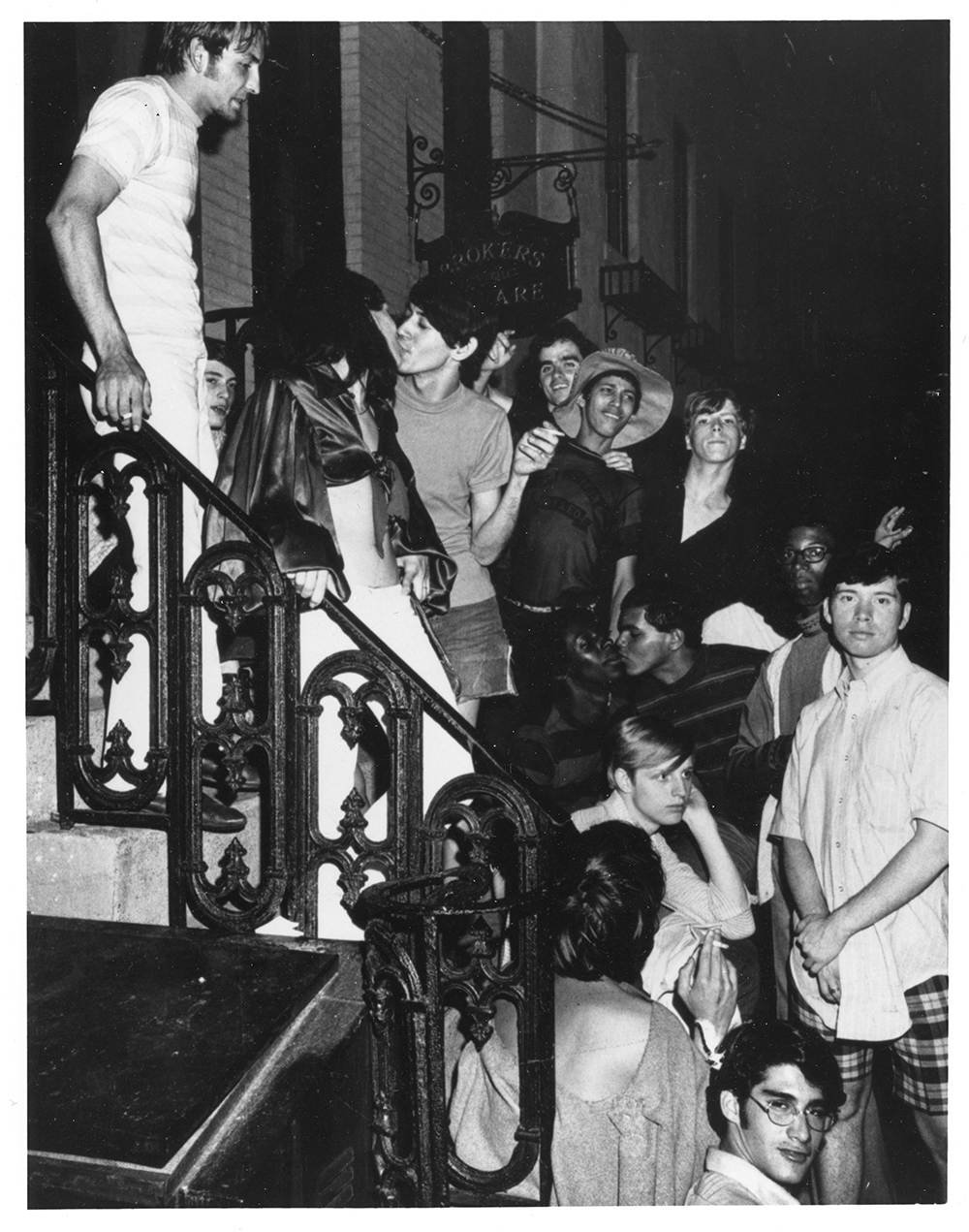

June 27, 1969. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

June 27, 1971. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

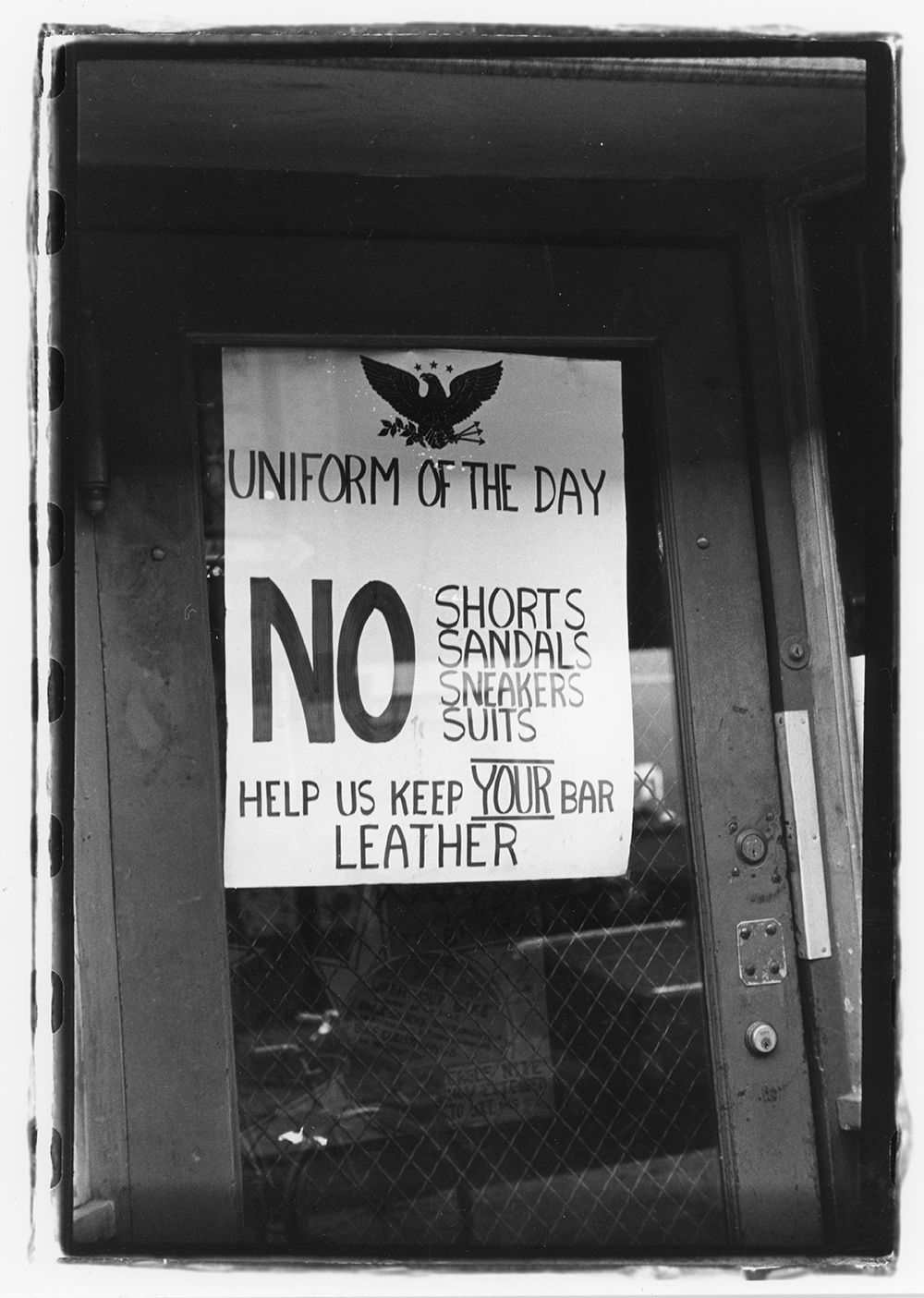

The Eagle Tavern on the waterfront, August 31, 1971. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

The Miss All-American Camp Beauty Pageant held at New York’s Town Hall, February 20, 1967. Miss Philadelphia won first place. The judges included Terry Southern, Larry Rivers, Rona Jaffe, Jim Dine, Baby Jane Holzer, Paul Krassner, and Andy Warhol. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

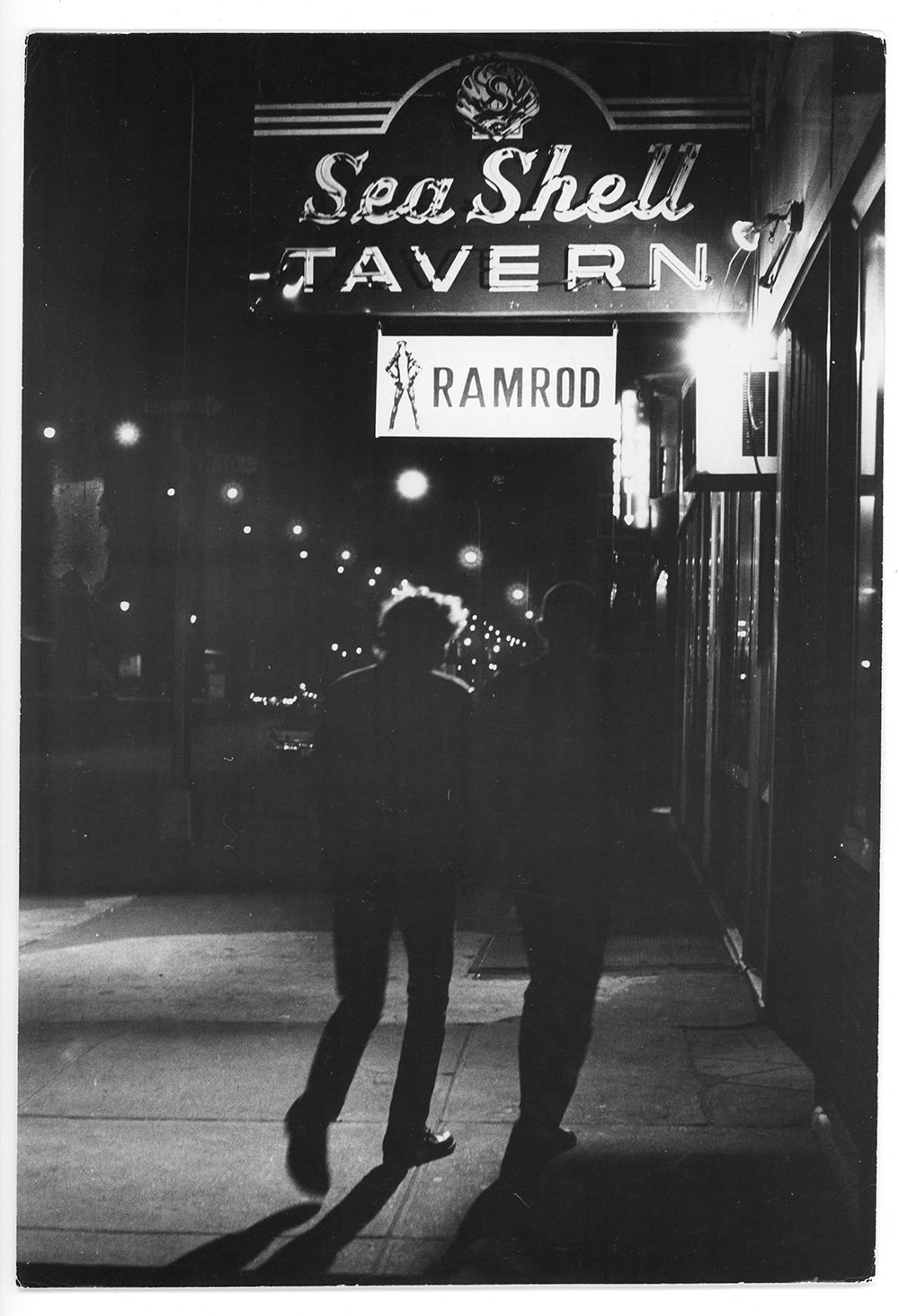

The Ramrod: the most popular waterfront bar on West Street. March 2, 1973. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

In Central Park after the first Stonewall anniversary march, June 28, 1970. Photograph by Fred W. McDarrah, from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall (OR Books 2019).

All images from Pride: Photographs after Stonewall, by Fred W. McDarrah, reissued by OR Books this month.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2RNohtO

Comments

Post a Comment