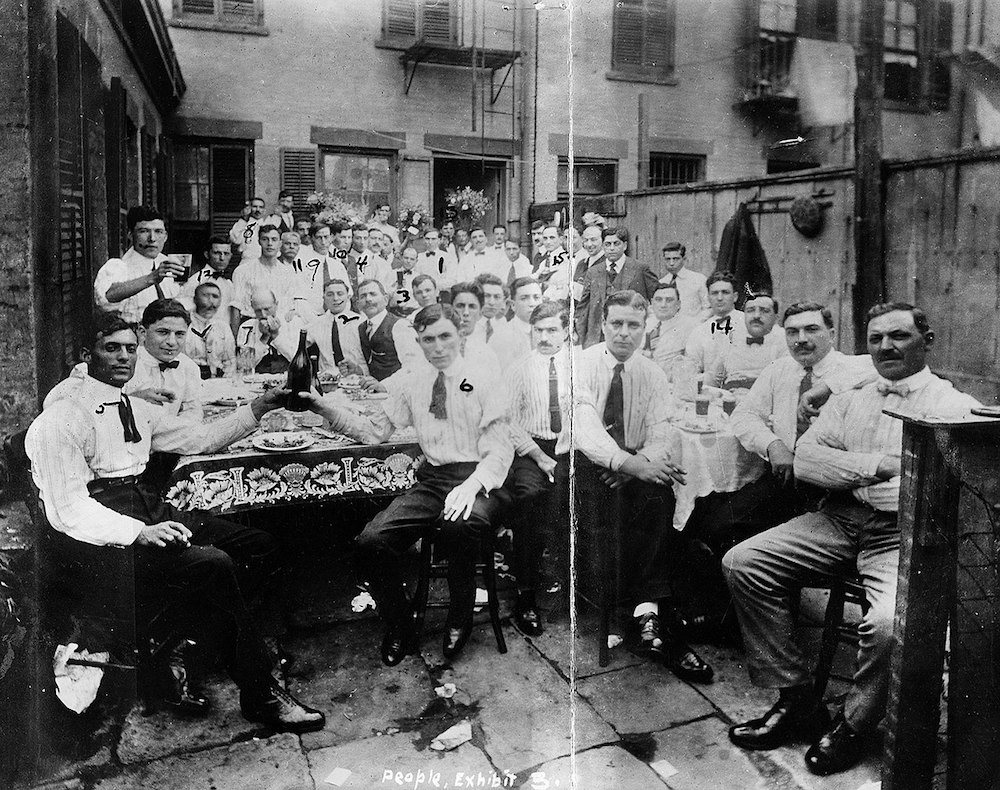

Photograph of the Navy Street gang in Brooklyn, New York, used as a prosecution exhibit at trial in 1918. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

I grew up on gangster stories. While other kids were hearing about the Three Little Pigs and the Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe, my father was telling me about the legends of his New York childhood—Pittsburgh Phil Strauss and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky, the visionary who put craps up on a table. “The lesson here,” my father said softly, as I lay in bed, “is that it was the same game, just played on a different level.”

For a kid in the suburbs, these stories were more than stories—they were redbrick stoops, air shafts crossed by clotheslines, alleys, candy stores and subterranean club rooms, apartment houses that, compared to my atomized world of detached single family living, seemed like paradise—coastal Brooklyn, where the fog bathes everything in a ghostly light and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge vanishes halfway across, like a ladder with its top in the clouds.

As soon as I was old enough, I moved to New York. I said I was looking for a job, but I had really come in search of the truth behind my father’s stories. This became my career. Parents: be careful what you tell your children at night. I explored the parts of the city where I knew the old-time gangsters had operated. Little Italy and the Lower East Side, East New York and Brownsville, the piers that had been the heart of the old Fourth Ward. I was consumed by New York history—not the story of marble buildings and glad-handing mayors but the alternate story that ran parallel and beneath: the story of the underworld, its heroes and stool pigeons, founders and visionaries. As my father said, “the same game, just played on a different level.”

In time, mostly but not entirely working in my capacity as a reporter, I came to know some living examples of the genus and species: New York gangster. The young toughs loitering in front of the Ravenite Social Club on Mulberry Street circa 1990; outer-borough boys done up like canaries, in yellow and green; and, still more interesting, the old-timers who’d started their careers when the last of the ancients were still throwing lightning bolts. I spent an afternoon shadowing one of the men around St. Vincent’s Triangle in the Village asking about the way things used to be. They said he was feeble-minded, but that was an act. I found another gangster in New Jersey. (“I can’t handle you in town,” he said. “Meet me at the Meadowlands Complex. That’s mine. From there to Asbury Park, it all belongs to me.”) He said he’d talk to me, “ ’cause I met your father at La Costa, and he treat me real cordial.” When I told my father, he said, “If you write about Johnny, write nice. If he doesn’t like it, it’s not a letter to the editor he’s gonna send.” I met a boss of bosses, capo di tutti capi, at Bert Young’s restaurant on East Gun Hill Road in the Bronx. Dozens of members of the Genovese crime family had been arrested and made bail and were celebrating. The boss knew my book Tough Jews, the first installment of this grander gangster project. The story of the Brooklyn mob Murder Inc., it centered on Abe “Kid Twist” Reles, who, after testifying against members of his own gang, was tossed out a window of the Half Moon Hotel on Coney Island. He was dubbed “The Canary Who Could Sing But Couldn’t Fly.”

“I wouldn’t put him in my fuckin’ book,” the boss told me. “Maybe it’s history, but Reles was nothing but a goddamn rat.”

When I asked the boss who he would put in his book, he smiled and said, “There are so many.”

I suddenly realized that these men had also grown up on gangster stories told by their fathers. The boss recalled some of them, then encouraged me to track down the biographies. When I did, I found still other men who’d been raised on gangster stories. No matter how far back I went, in fact, I found still older old-timers talking about still more ancient days. It was an infinite regress. It went on and on, fading to an age so distant it was lit by kerosene lamp. It gave me a mission, inspired a quest: I would track down and name and chronicle the very first New York gangster, the man behind all the other legends.

Many consider Monk Eastman to have been the first. He led a gang called the Eastmans, had a pocked face and scary eyes, fought battles on Orchard and Cherry Streets, served in World War I, and was found dead outside a dance hall on Fourteenth Street in 1920. But when Eastman turned up in the dives, old-timers were already telling stories about gangsters of an earlier generation. If you figured out who those gangsters were actually talking about, you’d establish the bedrock beneath the underworld, the source of all that criminal energy. You might come to understand the alchemical process that turns psychopaths into folk heroes. You might even unlock something fundamental about New York. In this way, lantern in hand, I continued until I reached the Mesozoic era of the Manhattan underworld, when the earliest mobsters emerged from the primordial ooze. Little Augie Fein, gunned down on the corner of Norfolk and Delancey; Mose, the otherwise nameless thug who would pass his cigar to an underling before a fight, saying, “Hold de butt”; Bill “the Butcher” Poole, whose last words were, “Goodbye, boys, I die a true American!” These were some of the first bad men—but who were they telling stories about at bedtime?

Albert Hicks is the closest thing the New York underworld has to a Cain, the first killer and the first banished man, carrying that dread mark: MURDER. He operated so long ago, in a city so similar and yet so different from our own, the word gangster had not yet been coined. He was called a pirate.

For years, he operated out of the public eye, rambling from crime to crime, working under an alias, sleeping in the nickel-a-night flops that filled the lower part of Manhattan, drinking in barrooms where the great entertainments were rat-baiting and bear-baiting—patrons wagered on how many rats a terrier could kill, on how many dogs it would take to bring down a bear. In 1860, Hicks was New York’s most feared man. This was Manhattan as dark fairy tale, an early draft that would be overwritten until it became a palimpsest. Even now, everywhere you look, reminders of that ancient city bleed through: at Peck Slip and the East River, a neighborhood once lousy with tall ships, blind pigs, and sons of bitches, a pirates’ playground; at Hangman’s Elm in Washington Square Park, a three-hundred-year-old tree said to have once served as a gallows for public executions; at Stillwell Avenue and the Boardwalk in Coney Island, where Lucky Luciano sat his boss Joe Masseria at a poker table, then stepped aside as a squad of hitmen, including Bugsy Siegel and Joe Adonis, came through the door. Asked where he’d been during the shooting, Luciano told police, “Taking a pee; I always took a long pee.”

Hicks came to New York to make his fortune. He did it in crime, but he can stand as an alter ego for all those strivers who reach the city in search of success. He worked on the water; he worked in ships. He became notorious in the worst neighborhood Manhattan had ever known, the Five Points, where Anthony Street, Orange Street, and Cross Street came together to form the edge of Paradise Square. That New York was a sugar-and-salt mix of politics, business, and brutality. We know about the early political leaders: Peter Stuyvesant and Fernando Wood. We know about the pioneering tycoons: Cornelius Vanderbilt and J. P. Morgan. Albert Hicks was a founding father same as them, only he was a founder of New York’s underworld. His story was passed down by word of mouth, told and retold until it became a legend. It was officially recorded just once—in the press, as it unfolded—then shifted from breaking news to tall tale, added to and tarted up as time passed. If it’s not been properly chronicled since the summer of 1860, it’s partly because these events took place on the eve of the Civil War. That conflagration overhangs this story like the shadow of an incoming comet. In a moment, everything would be blown away.

To research these events, I relied on police records, court documents, and newspaper accounts. The spirit of the time is less in the details of those articles than in the tone, the cacophony of voices, the competitive jostling between the New York Herald, the New York Sun, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and the New York Times. There were dozens of daily papers, evening and morning editions, as well as weeklies that offered deeper analysis. In obsessing on Hicks, in reading the old books and newspaper columns, I came to understand the city in a new way. All the good and all the bad were already in place in 1860. Everything that’s happened since has merely been a dreamlike elaboration.

Even contemporaneous writers knew Albert Hicks was something other than a normal killer. He was a demon. He had that kind of charisma. He put his arm around the town and pulled its people close. In writing about him, reporters of the time were capturing a new kind of terror—the terror of the metropolis, its anonymity, all those tenements and all those windows, all those docks and all those harborside taverns, all those numbered streets and all those mysterious lives. Albert Hicks personified the freewheeling city that would have to make way for the modern metropolis. He was Manhattan as it had been when pirates anchored off Fourteenth Street. The hero of the lunatics, a first citizen of a criminal nation, the subject of ancient bloody bedtime tales.

His final spree played out like a ghost story, only it happened to be true.

Rich Cohen is the author of The Last Pirate of New York: A Ghost Ship, a Killer, and the Birth of a Gangster Nation.

From the book The Last Pirate of New York: A Ghost Ship, a Killer, and the Birth of a Gangster Nation, by Rich Cohen, published this week by Spiegel and Grau, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2Xq21YF

Comments

Post a Comment