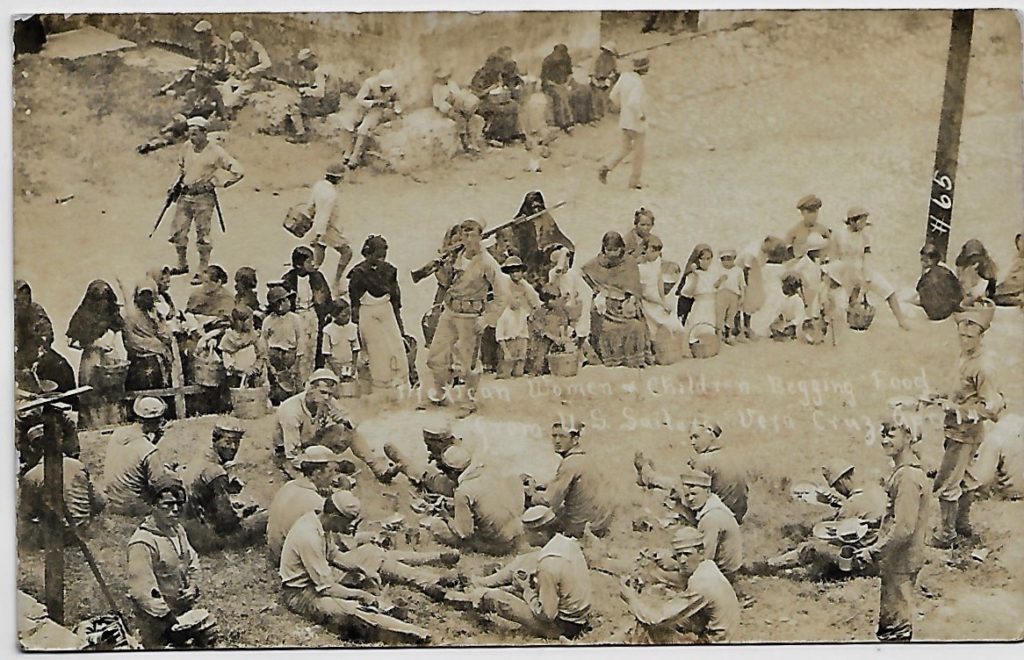

In the spring of 1914, nine American sailors were arrested by the Mexican government for unauthorized entry into a loading area of the oilfields in Tampico, Tamaulipas. They were released with an apology, but without the twenty-one-gun salute also demanded by the United States naval commander. President Woodrow Wilson ordered the fleet to prepare for an occupation of the port of Veracruz. They were to await authorization from Congress, but then news of an arms shipment headed for the port overrode that formality. The weapons, procured by an American arms dealer, were destined for the newly self-appointed president of Mexico, Victoriano Huerta, who had been assisted in his coup d’état by the American ambassador; despite this, the United States sided with his rival. Battleships and cruisers landed a force that would ultimately number some 2,300. In the city they met with fierce resistance from determined but poorly equipped local citizens. The occupation lasted seven months. This picture, taken by Walter P. Hadsell, an American photographer resident in Veracruz, was published as a (silver gelatin) postcard and enjoyed wide circulation, even being bootlegged by other photographers.

The worldwide postcard craze was at its peak in the spring of 1914 (it would largely succumb to the conflict in Europe starting that August). The Mexican Revolution (1910–20) in its many phases was documented in postcards, by photographers on both sides of the border. The pictures did double duty, as news photos (the folder on the Mexican Revolution in the New York Times morgue is filled with cards mailed to the offices from the front) and as snapshots in which potential purchasers might see their own image. American sailors in Veracruz might, for example, send home a picture showing themselves enjoying a hearty lunch, guarded against a ravenous crowd of Mexican women and children. The photographer chose to center the women and children, although they appear largely featureless, while taking care to depict as many American faces as possible. This card, as crisp as the day it was badly printed, was perhaps preserved in an album for the better part of a century, a remembrance of youth.

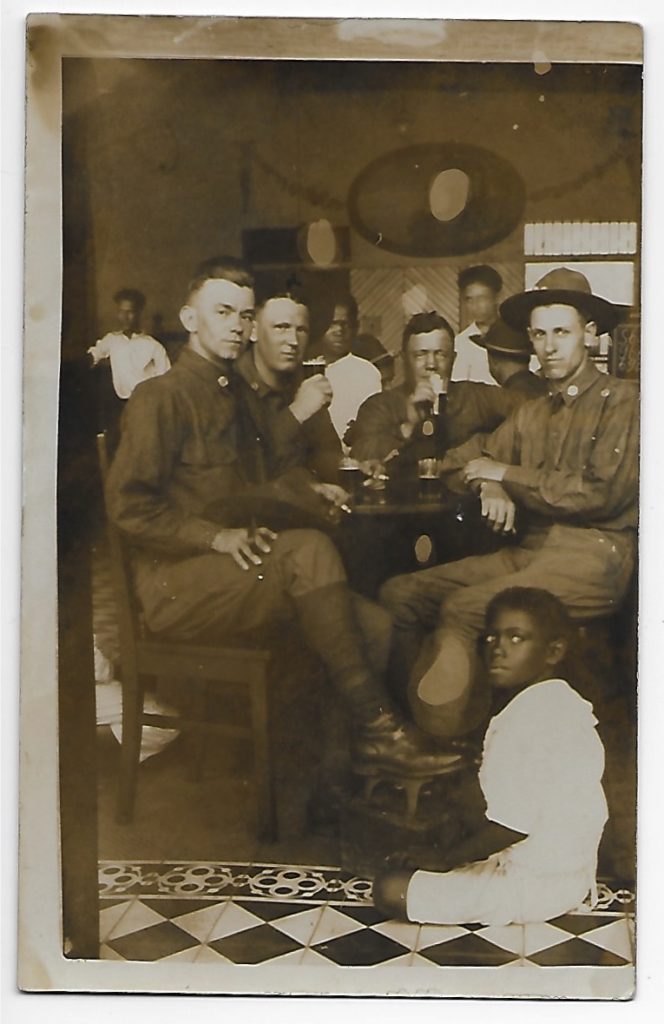

In pictures destined for the American trade, native inhabitants of countries entered by the American military generally appear as servants, beggars, or corpses. This unattributed postcard may date from the Border War, which raged at intervals from 1910 to 1919. The Americans are having a beer in a cantina, and the dark-skinned locals serve essentially as decorative accessories, along with the patterned floor tiles. The child of African descent at front right, who looks no more than eight or nine years old, is shining shoes; the American rests his foot on an iron step mounted on the shoeshine box. The proceedings are casual, but the picture is as formal as a court painting. The raised foot is in fact the center of the photograph, signifying dominance in explicit if rather superfluous terms. Despite the stains probably resulting from sloppy printing, the card was clearly carried around by its initial purchaser for some time, as a souvenir of a happy moment.

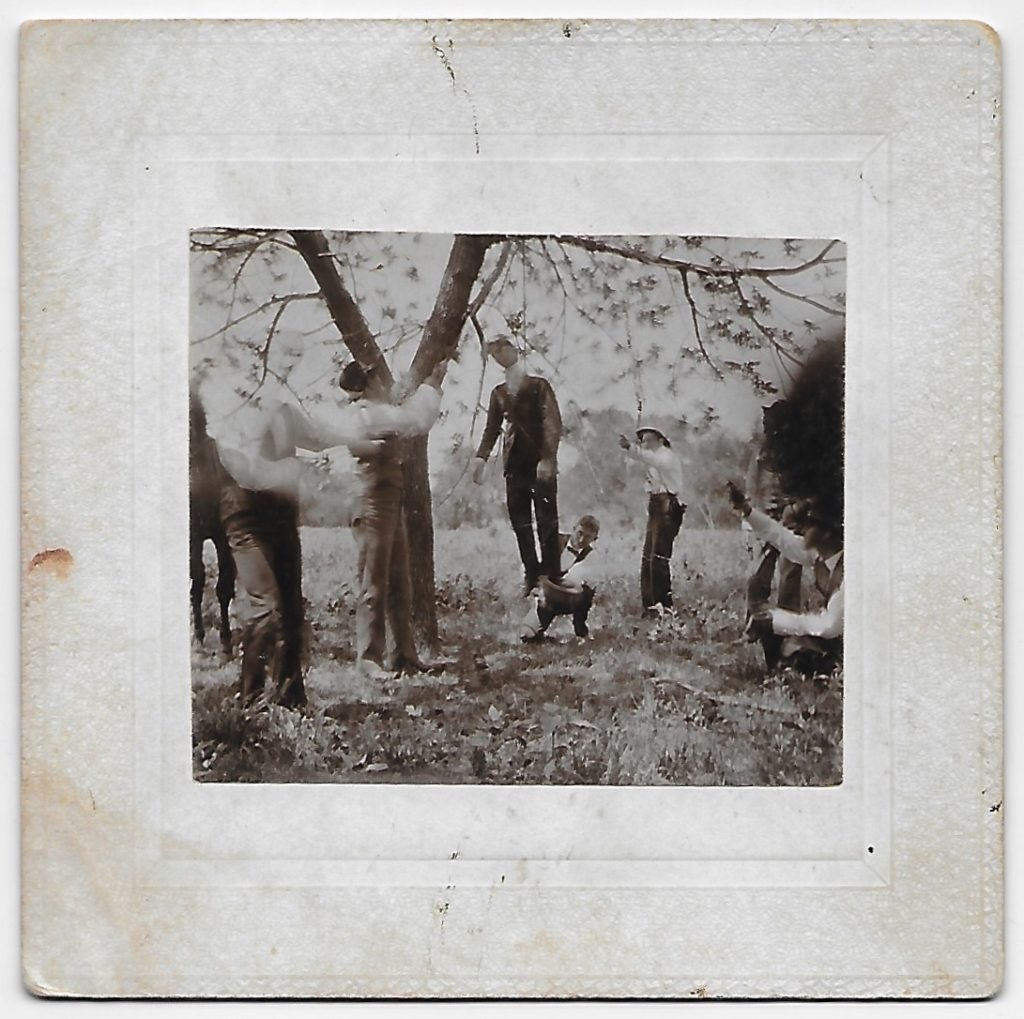

The so-called Bandit War was a subset of the Border War (itself a subset of the Mexican Revolution). Between 1915 and 1916, raids and skirmishes multiplied as parties of Mexican rebels made quixotic attempts to reclaim parts of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona that had been seized by the United States in the previous century. Each of these forays was met with bloody reprisals by the Americans. This photo postcard, by Walter H. Horne of El Paso, is not atypical of the documentation of the conflict; other cards show the bodies of dead Mexicans being dumped into carts, hauled away, buried. The pictures are trophies, intended for dissemination. This card, along with another similar shot, was mailed to me by a reader after I wrote an op-ed about the Abu Ghraib photos for the New York Times in 2004. I had described those snapshots of abuse—by U.S. military personnel of Iraqi prisoners—as trophy pictures, and that reminded my reader of the cards brought home by her grandfather. She seemed eager to get rid of them.

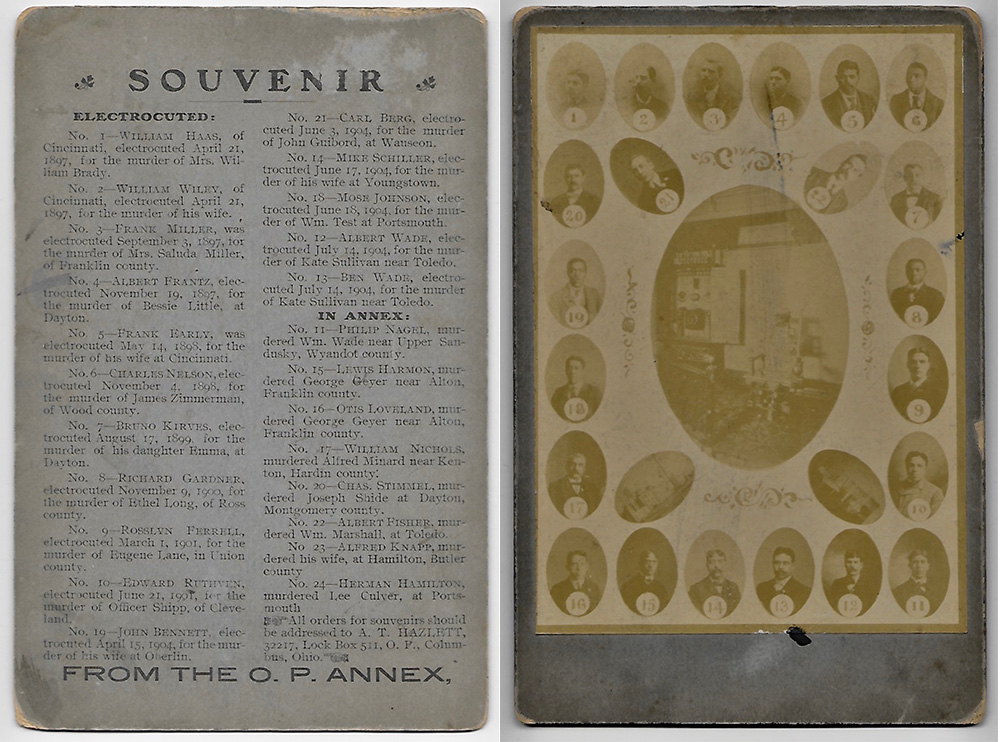

The memorialization of death was not limited to foreign conflicts. In 1904 you could mail away for this souvenir, which celebrates the use of the electric chair by the state of Ohio from 1897 until the summer of that year. In the center of the faded cabinet card is the chair itself, in an oval vignette bordered by decorative frills. Surrounding it are twenty-four numbered portraits, also in oval vignettes. Although the subjects of the portraits are as formally dressed as bankers, they are in fact victims of the chair. Sixteen of them have died in it and the remaining eight await their turn in the annex. The reverse gives their names, the barest outline of their alleged crimes, and their dates of execution, if applicable. Who bought this picture? Were the purchasers drawn by a sense of justified revenge, or by civic pride in the modernity of the equipment? Did they mount it in an album or display it on the mantel? Was it a conversation piece? Was it intended to serve as a warning to their errant children? Did they perhaps imagine throwing the switch themselves, fully empowered by the law to administer death?

All of the above are commercial objects, produced in significant numbers (aside from the cantina picture, probably made on spec). They were not exceptional. There are hundreds of postcards of death from the Mexican conflict, and there are postcards of electric chairs in other states in later years. And then there are the unspeakable photos of lynchings, primarily of African Americans, that circulated as cabinet cards and postcards in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I won’t show you any of those. The bottom photo will have to substitute: it depicts six men stringing up and aiming guns at what appears to be a dummy; I can provide no context. The United States is perhaps not the most violent country in the world, and certainly not the worst colonial oppressor, but few other nations have ever produced photographs like these. There are commercial photographs of executions in China during the Boxer Rebellion; they were produced by Europeans, as exotica. There are photographs of various atrocities in various conflicts; they were made to inspire outrage and usually circulated by hand in small numbers. The American model of vicarious death dealing is fairly singular. Trophy pictures are a form of savage entertainment, thinly justified by legal pretext. The atavistic residue of this pursuit surrounds us every day. The cruelty is the point.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2Lnx0le

Comments

Post a Comment