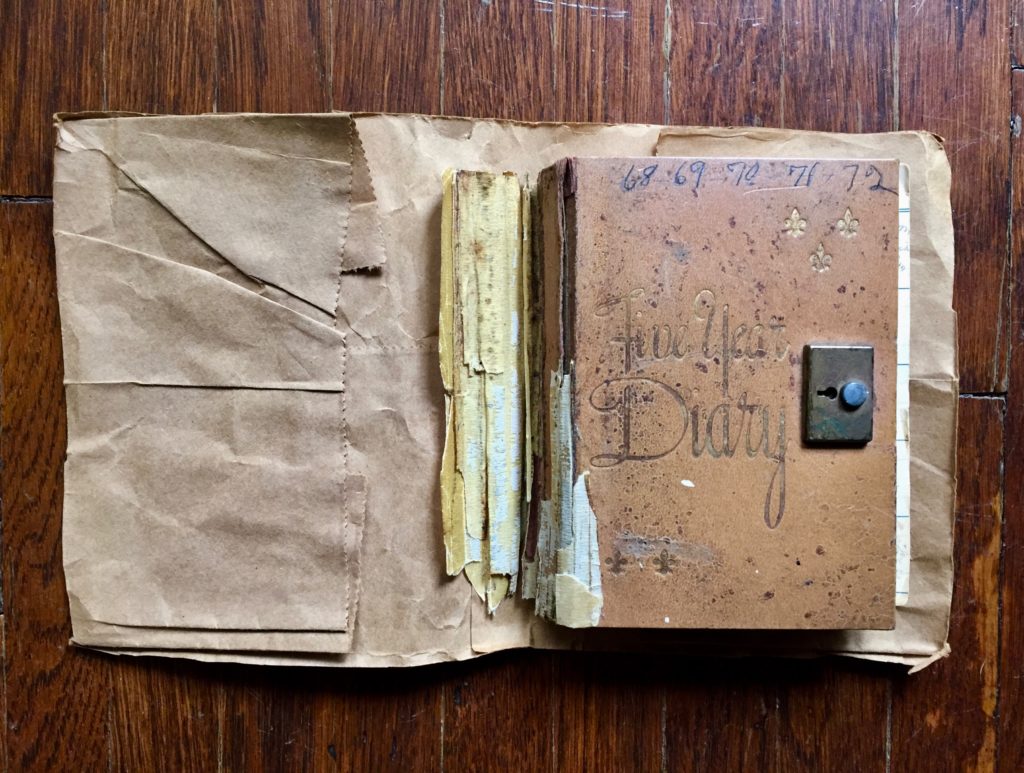

I had her diary in the top-left drawer of my desk, held together by the cut-out bottom of a paper grocery sack. She’d been eighty-six years old in 1968—the first of the five full years she recorded. I didn’t know her. I had her diary because the person who’d previously possessed it passed away, and when their effects were sold at public auction, the diary—discarded, unwanted—ended up in my hands.

I searched for her online in 2004 or 2005 or 2006. I may have searched again in 2007 or 2008 or 2009. I couldn’t find her—not even an obituary. I wanted to know more, but when I was not able to find it, I stopped wondering. This was a life not retrievable by search engine, I thought. There was something pleasing in that.

The diary became something I took out often to look through, to read, to think about. It had none of the posturing I’ve seen in other diaristic endeavors, none of the tortured self-evaluation. Instead, the diarist wrote about bodily dailiness: weather, meals, sleep, hobbies, housework. Fire whistle in night. Steady rain at 8. He brought us some mush to fry. She wrote about the people she knew: their comings and goings, their physical and emotional states, their deaths. Maude ate good breakfast, oatmeal, poached eggs, little sausage. Maude ate her dinner pretty good. Had letter from Bertha she better and contented out there.

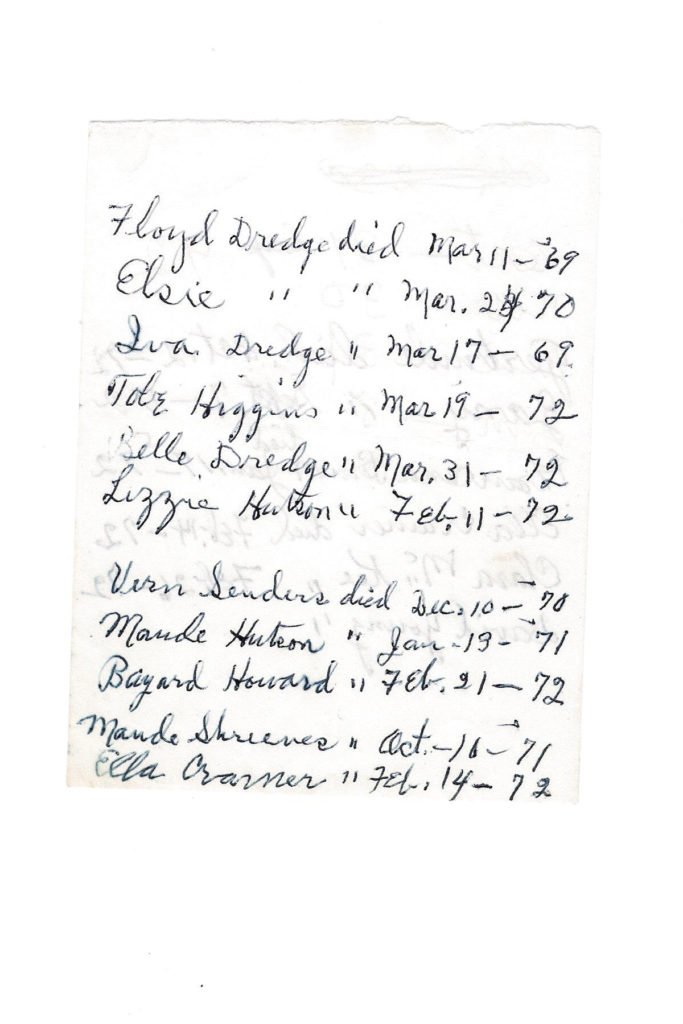

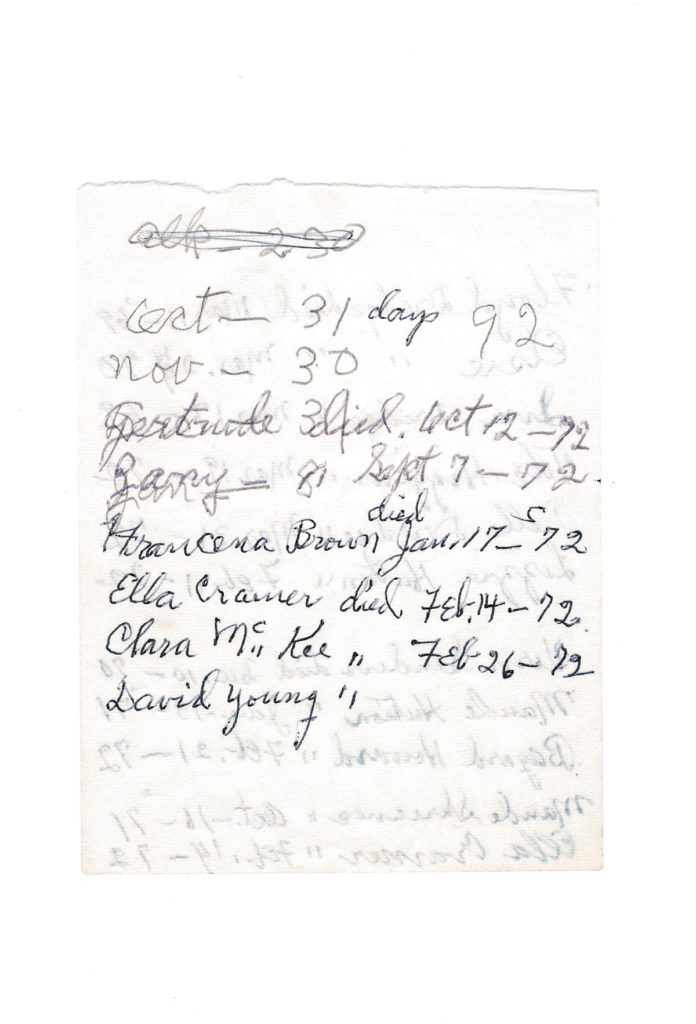

She wrote often of visiting the town’s cemetery with her daughter. They tended the graves of family members or checked on their own headstones—already bought, etched, and set in their plots. D. out to cemetery, her head stone is being put up. We went back out toward eve, stone looks very nice. It seemed to me she accepted the inevitably of her death, the death of others, with an enviable stoicism. Many people die in the pages of her diary—she made a separate list of the deaths that occurred between 1969 and 1972 and tucked it in the back—yet she continued to engage with her life in a daily, present way. Sure pretty out. Sure grand out. D. making a new piecrust. All better.

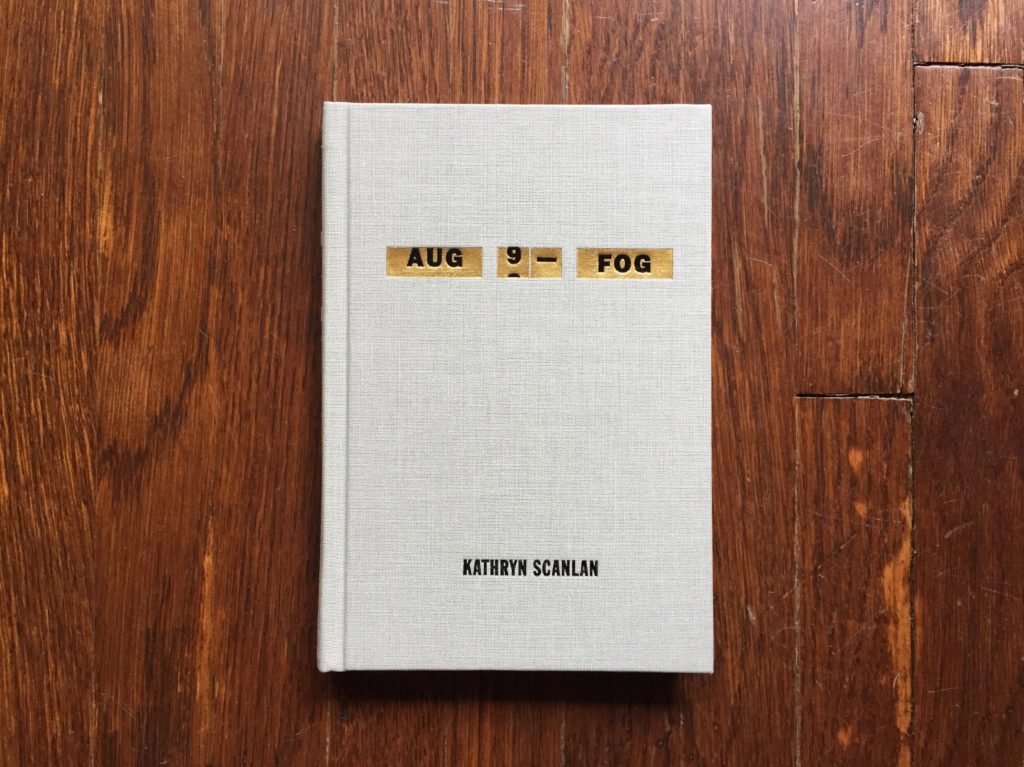

I read about the people in her diary without knowing their histories, their relationships. Who was Janie? Mildred? Ruth? Of course the diarist does not explain—why would she? This lack of narrative exposition excited me. The omissions created space, mystery. They felt profound, moving. I wanted to experiment with how an absence of information could create meaning. I began to view the diary as a formal challenge, a linguistic workbook. Over a period of ten years, I crafted my own text from it, published last week as Aug 9—Fog.

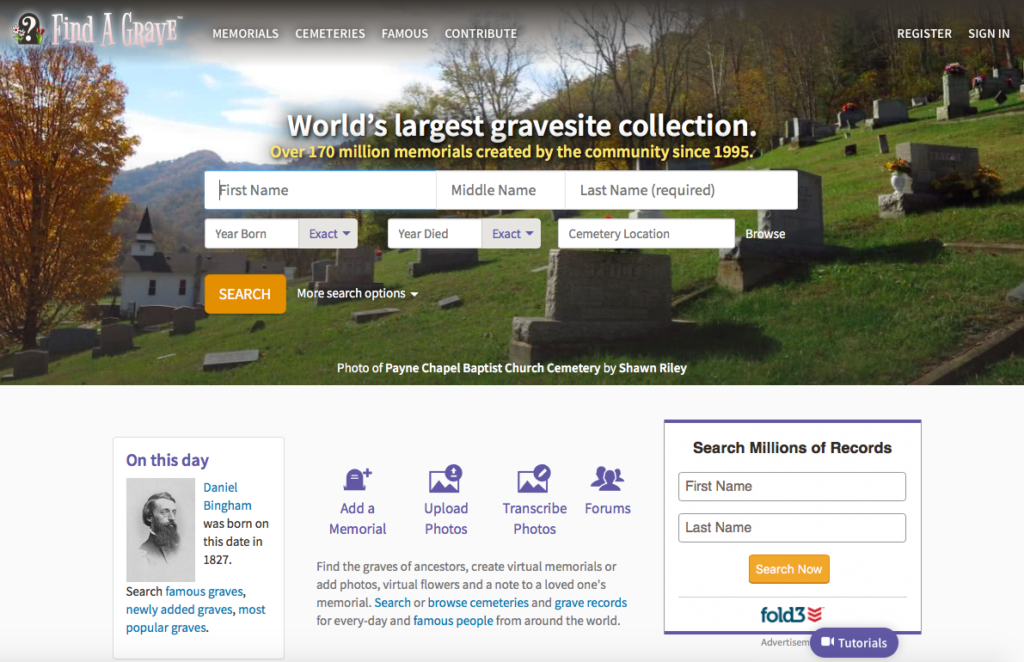

The unknowing was central to my book: for fifteen years, the diary—cryptic, riddle-like—held my interest with its silences. But then, last year, before the book went into production, I tried one last search for the diarist. I needed to know whether she had any surviving relatives. If she did, I wanted to contact them. This time, one result came up in my browser: the diarist’s full name linked to a page on a website called Find A Grave.

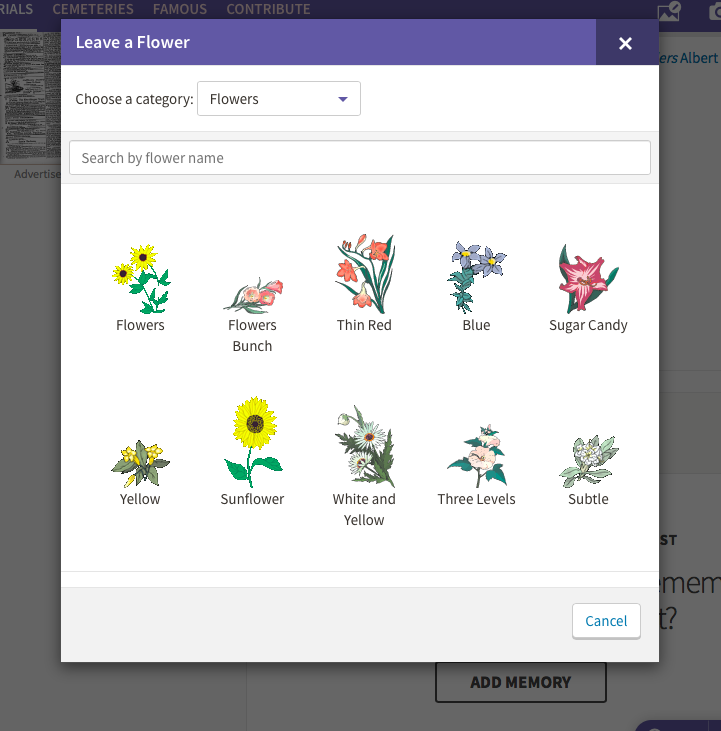

Members of the site—called ‘Gravers’—visit cemeteries and upload the photos they’ve taken of individual tombstones. A page is created for each tombstone, where the name and birth and death dates of the deceased are provided, as well as the cemetery in which they are buried. The page functions as a digital gravesite, where other Gravers may leave virtual flowers, ribbons, candles, stuffed animals, and messages.

It’s not technically a genealogy site, but because families are often buried in close proximity, and because Find A Grave’s format allows for adding links to the gravesites of spouses, siblings, children, and parents, partial family trees sometimes emerge.

In my introduction to Aug 9—Fog, I write, “the diary has ceased to be an entirely unique, autonomous other to me. I don’t picture her. I am her.” This line portrayed the mindset in which my book was composed. My creation was possible because the essential mystery of the diary opened a space in which I could imagine an “I” who was other, but also myself—otherwise known as the realm of fiction. My book would not exist without that space, without that leap of voice.

When I clicked on the diarist’s name, I was confronted with a photo of her gravestone, her birth date, her death date. Below that were links to the gravesites for the rest of her family. I recognized many of the names—these were people I’d read about for years without knowing their relationship to the woman who’d written about them, but now they were arranged in a way I understood. Here was Lee, her brother. Here was Bayard, her sister’s husband. Here was Bucky, her niece’s son.

I learned the diarist died four years after her diary ends—three weeks before her 96th birthday.

I learned her husband—father of D., the daughter with whom she lived while writing the diary—died two years into their marriage, a year after D. was born.

I learned she married again, ten years later, and that her second husband died nine years after that from a condition now easily treatable with B12 shots.

She was sixteen when her brother died, nineteen when her sister died, twenty-three when her first husband died, twenty-six when her father died, twenty-seven when another sister died, forty-three when her second husband died, fifty when her mother died, sixty-five when her last sister died, and ninety-five when her last brother died.

I messaged one of the users who’d helped create the diarist’s page. She wrote back, and I’ve been corresponding with her since. Her husband is a distant cousin to the diarist. She and some other relatives are genealogy hobbyists. I sent them the scan I’d made of the diary—almost four hundred pages long—and, recently, copies of my book. They confirmed what I’d been inclined to believe—the diarist had only one child, a daughter, and because that daughter had no children of her own, the diarist’s immediate family line ended when her daughter died in the late 1990s.

As these revelations accumulated, and as the prospect of my book’s publication became more concrete, a strange shift began to take place in my mind. I expect it’s the case for most authors—having labored in private so long—to feel a sudden, disorienting distance from their creation as it becomes a tangible object in the world. But in my case this distance was doubled—I felt more and more removed from the book I’d made, but I also felt that its source—the diary, its author—was shapeshifting, becoming something other than what it had been in my mind.

I’ve been struggling to write this essay for months. Recently I realized my resistance was coming in part from this: central to the story is a disappointment in its fulfillment. At any point in the fifteen years I’ve owned the diary, I could’ve visited the diarist’s town—she’d written her address on the front page beneath her name, and the town was less than an hour from where my parents lived—but I hadn’t. I didn’t want to know where she’d lived. I didn’t want to look for her grave in the cemetery. Now, though, I’ve seen it on my computer and—on a cold, sunny day this past March—in person. The project of Aug 9—Fog has always been about death, yet that didn’t prepare me for the somber, sobering encounter with the diarist’s mortality.

The more that’s revealed to me about her life, the less I feel this ownership, this kinship—or maybe it’s that I feel there are two diarists now: the private one I created and the real one with whom I am now confronted. As the real woman expands in detail, the private one shrinks. Presented with the stark, unequivocal details of the real woman’s life and death, the private one undergoes a death of her own.

I am glad to have found the diarist’s relatives, glad to be able to share the diary and Fog with them. But the price of this is a puncture, a deflation of the reality—or unreality—I’d made. It feels like an origin story in reverse: in finding the woman, I’ve lost the woman. Face to face with a photo of the diarist’s grave, I was forced to realize I was not, in fact, her—was not now, had never been. It had been me all along.

Kathryn Scanlan‘s work has appeared in NOON, Fence, Granta, and Egress.Her book Aug 9-Fog was published by MCD x FSG. Her debut collection of stories, The Dominant Animal, is forthcoming from FSG Originals in 2020. She lives in Los Angeles.

from The Paris Review http://bit.ly/2XFyACb

Comments

Post a Comment