The first time Jack Kerouac’s name appeared in the press was August 17, 1944, when he and William Burroughs were arrested as material witnesses to murder. While the headlines were consumed that day with news of the Allies’ successful landing on the southern coast of France, the murder was sensational enough to make the front page of the New York Times: “Columbia Student Kills Friend and Sinks Body in Hudson River.”

With noirish drama, the newspaper called the murder “a fantastic story of homicide”: a nineteen-year-old undergraduate had stabbed his older companion several times with his Boy Scout knife in the early morning hours in Riverside Park on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “Working with frantic haste in the darkness, unaware of whether anyone had seen him,” the article related, “the college student gathered together as many small rocks and stones as he could quickly find and shoved them into [the victim’s] pockets and inside his clothing. Then he pushed the body into the swift-flowing water.”

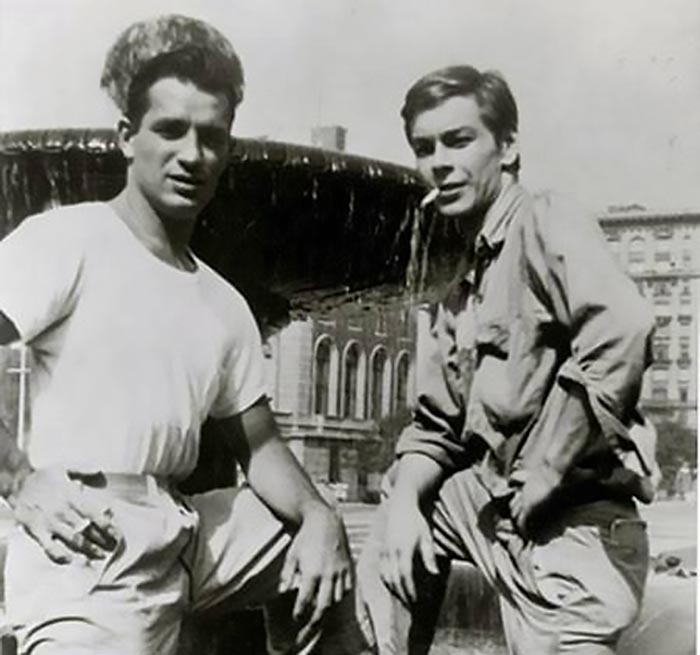

The student was the St. Louis native Lucien Carr, who possessed a mixture of delinquency, good looks, and intellectual charm. His victim was the thirty-one-year-old David Kammerer, a tall lanky man with dark-red hair and a high-pitched voice who was a friend of William Burroughs. The two lived near each other in Greenwich Village, where Kammerer worked as a building janitor. Months prior to the murder, through his friendship with Kammerer and Burroughs, Carr had met Kerouac and fellow Columbia student Allen Ginsberg.

Carr would later tell police he had visited both Kerouac and Burroughs in the early morning hours after he left Riverside Park, and both were then arrested as material witnesses. Carr said when he showed up at Kerouac’s door, the two walked to Morningside Park to bury Kammerer’s glasses and get rid of the Boy Scout knife by dropping it down a storm drain. They spent the day drinking, visiting the Museum of Modern Art, and going to the movies before Kerouac convinced Carr to go to the police. Carr confessed to the killing even before Kammerer’s body surfaced in the Hudson near Seventy-Second Street.

It would be a few years before Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg would emerge as the leading voices of the Beat generation, but in the summer of 1944, those artistic origins were taking shape—and Kammerer’s murder would be a crucial part of it. At the West End Café, a local bar on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, they would talk of their literary idols and mentors, fostering the myth of the romantic rebel in the tradition of Rimbaud and Baudelaire. When Carr drank, he was known for his unpredictable behavior, chewing glass shards or throwing plates of food onto the floor. It was at the West End Café that Carr and Kammerer drank and talked late into that August night, before they ambled a few blocks over to Riverside Park.

*

Kammerer and Carr had met in St. Louis at a summer camp for boys, where Kammerer was an instructor and Carr a student. From a middle-class family, Kammerer earned a Ph.D. in English, and had taught literature and physical education at Washington University. What started as an infatuation turned into a decade-long attraction. He followed the young Carr across the country, from Andover, to the University of Chicago, to Bowdoin College in Maine, before moving to New York City when Carr entered Columbia University. The Burroughs biographer Ted Morgan related that while many believed these moves reflected Carr’s attempt to “get away from Kammerer,” others were dubious, for “when you saw them together, they seemed to be the best of friends, drinking and horsing around.” In his police confession, Carr claimed that over the years of their acquaintance, Kammerer had several times “made improper advances to him, but that he had always rebuffed the older man.”

The phrase improper advances was not new to crime stories in the forties. Since the late nineteenth century, such terms were common in the press to describe verbal and physical assaults on women. They connoted criminal actions that simmered with sexual abuses too shocking to make explicit. While the terms improper advance or indecent advance appeared in queer crime stories in the thirties, it was in the post–World War II years when such terms used in the press and the courtroom came to embody the perceived threats of homosexuals on the home front.

Initially, Assistant District Attorney Jacob Grumet had doubts about Carr’s confession, telling the New York Times he “was uncertain whether he was dealing with a slayer or a lunatic.” Determining whether the crime was the work of a vulnerable teenager or a crazed, psychopathic queer lover would become the compelling question for detectives and journalists alike. Solving this mystery depended on solving the riddle of Carr’s sexuality.

Initial press accounts described Carr with a myriad of unmanly attributes, including “a pale slender youth,” “refined,” and “a frail blond youth,” “whose frail build and earnest expression might easily arouse sympathy.” The New York tabloids presented the teen as a helpless victim of a psychotic homosexual attack. The Daily Mirror called the crime a “twisted sex murder.” The New York Daily News described Carr’s stabbing as an “honor slaying.” The Daily News contrasted the “mild” expression on Carr’s “young face” against the “33 year old former English teacher” who, Carr claimed, was “a homosexual.” In drawing this contrast between youthful innocence and sexual deviance, it was often difficult to discern who was the real victim of the crime.

By September, when Carr entered a guilty plea of first-degree manslaughter, the Assistant District Attorney believed that Carr “had not intended to kill Kammerer, a homosexual, but that Kammerer for more than five years had persisted in making advances to Carr, which always were repulsed. Kammerer’s persistence,” the prosecutor added, “had made young Carr ‘emotionally unstable.’ ” In her testimony, Mrs. Carr described Kammerer as a “veritable Iago” who had corrupted her son “purely for the love of evil.”

*

Unlike the initial press accounts of Carr, Jack Kerouac’s sexuality was never in question; nearly every article noted that the handsome Kerouac was soon to be married. While he was still being held as a material witness, the New York Times noted, “the police escorted Kerouac to the Municipal Building on Tuesday to witness his marriage to Miss Edith Parker of Detroit and then took him back to Bronx prison.” Such public displays of heterosexuality countered suspicions the prosecution and the detectives might have had about Carr’s defense.

In fact, the twenty-two-year-old Kerouac, according to the biographer Ellis Amburn, was struggling with his own sexual desires that summer, torn between his feeling for Lucien Carr and pressure to marry the wealthy Edie Parker. Kammerer had become intensely jealous when both Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg competed for Carr’s affection. Ultimately, Kerouac and Carr formed a close relationship. Kerouac affectionately called Lucien “Lou,” and Carr returned such affections with his usual impertinence, calling Jack his “has-been queen.”

Such playfulness underscored Kerouac’s conflicted feelings about his own queer desires—what Amburn terms Kerouac’s “homophobic homoeroticism.” In his 1958 novella The Subterraneans, the Kerouac character encounters a sexual solicitation by a man in Riverside Park, the same park where Kammerer had been murdered. “How you hung,” the man asks, to which Kerouac replies, “By the neck, I hope.” The novel also includes a well-known tryst between Kerouac and the young writer Gore Vidal in the Chelsea Hotel. In the novel, Kerouac portrays the encounter with decidedly vague descriptions, casting his protagonist in the position of rough trade—a role that accommodated queer sexual forays while not threatening his essential heterosexuality.

Years later, Vidal would recount his version of the incident in his memoir Palimpsest. In August 1953, Vidal was drinking with Kerouac and Burroughs at the San Remo bar in Greenwich Village. After Burroughs left, Kerouac suggested the two get a room at the Chelsea Hotel. Vidal described the hotel encounter as “classic trade meets classic trade,” prompting an awkwardness about “who will do what.” While the term trade referenced working-class men who have sex with other men for pay (often assuming the active role in sex), it also embodied a queer hypermasculinity against more effeminate gay men. In Vidal’s retelling, Kerouac submits to Vidal’s more aggressive play. “Jack raised his head from the pillow to look at me over his left shoulder,” Vidal writes. “He stared at me for a moment—I see this part very clearly now, forehead half covered with sweaty dark curls—then he sighed as his head dropped back onto the pillow.” While just a few months after this encounter Kerouac referred to Vidal as a “little fag” in a letter to the literary critic Malcolm Cowley, the night at the Chelsea Hotel would exemplify the unease that Kerouac felt toward his sexuality throughout his life.

*

This unease was not only a private matter but also one for the detectives in 1944. When police arrested Kerouac as a material witness, they held him in the Bronx jail. “During liberty period,” according to the biographer Amburn, young, good-looking “Mafia hit men went to Jack’s cell and attempted to seduce him. A friendly plainclothesman had already warned Jack that the ‘stoolies’ had been promised fifty years off 199-year sentences if they could prove that Jack was gay.” This experience would remain vivid for Kerouac over two decades later when he wrote his fictional autobiography Vanity of Duluoz: An Adventurous Education, 1935–46 in the late sixties. In one scene, as he and Claude (named for Carr) are waiting for the arraignment hearing, Claude whispers “out of the corner of his mouth: ‘Heterosexuality all the way down the line.’ ” This pledge becomes a refrain for the two as they sit in front of the detectives investigating the crime. In a conversation with the lead detective, Kerouac portrays the interrogation as chiefly an exploration of his sexual preferences:

Me and O’Toole go in the other room, he says: “Sitdown, smoke?,” cigarette, I light, look out the window at the pigeons and the head and suddenly O’Toole (a big Irishman with a gat on his chest under the coat): “What would you do if a queer made a grab at your cock?”

“Why I’d k-nork him,” I answered staightaway looking right at him because suddenly that’s what I thought he was going to do. But anyway O’Toole immediately takes me back to the D.A.’s office and the D.A. says “Well?” and O’Toole yawns and says “O he’s okay, he’s a swordsman.”

At the end of Vanity of Duluoz, Kerouac upholds the commitment he made with Carr in 1944: heterosexuality all the way. “Claude was a nineteen-year-old boy,” Kerouac writes, “who had been subject to an attempt at degrading by an older man who was a pederast, and that he had dispatched him off to an older lover called the river, as a matter of record, to put it bluntly and truthfully, and that was that.” The term pederast illustrated the anxious distinction between tough masculinity Kerouac valorized and the effect of the unmanly homosexual, who inflicted both physical and psychological harm on normal men, that he saw in Kammerer. This was the cornerstone of Carr’s defense, as his psychological trauma became a strong mitigating factor in the court’s decision. “He has gone through a terrible experience,” Carr’s attorney stated, “but medical experts say he can be rehabilitated.” The judge agreed and sentenced Carr to eighteen months in the Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York.

Carr’s form of homosexual panic not only became a powerful story about the Beats in those early years; it also pointed to an increasingly convincing defense for the murders of queer men in the many decades to follow. Whatever the motive for Carr’s violence, the story of Kammerer’s murder encapsulated a compelling and troubling idea in the popular imagination that took root in the forties and grew in the years after: assertions of heterosexual masculinity were defined by violent reactions against queer men.

*

In his journals, composed a few days after the murder, Allen Ginsberg wrote: “The libertine circle is destroyed with the death of Kammerer.” On one page, he pasted the New York Times article reporting on Carr’s indictment for murder, placing it among a series of entries about dreams he was having about his lonely outings in the city, each haunted by Kammerer’s death. He also recorded notes for a novella he wrote for his creative writing class—a work that shocked many faculty in the English department for its queer content. In one section entitled “Death Scene,” Ginsberg transmuted the violence into an erotically charged moment caught between murder and sex: “Choose to present me with your pecker or your knife,” Kammerer whispers to Carr in the darkness of the park. In response, Carr’s eyes “maddened in conflicting ecstasies of fear and desire.” While Ginsberg’s retelling may have been part of his own infatuation with Carr, it illustrates the nervous tensions between embracing and repulsing homosexual desires.

Just months after Carr’s sentencing, Kerouac and Burroughs began their own fictionalized account of the event in a novel that alternated narrators, each writer composing different parts of the story. Entitled And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, the book was finished in the spring of 1945 and was sent off to the publisher Simon and Schuster. Rendered in the matter-of-fact style of detective fiction, the novel focuses on two characters modeled on Carr and Kerouac who are trying to get a post on a merchant marine ship and sail off to France. The murder is moved from the river bank of a park frequented by queer men to a warehouse in Greenwich Village. After breaking into the warehouse, Phillip and Al (the character names for Carr and Kammerer) find a hatchet and start breaking windows. On the rooftop, Al confesses that he wants to ship out with Phillip and “do things you do.” He then tries to put his arm around Phillip. “I still had the hatchet in my hand,” Phillip confesses later, “so I hit him on the forehead. He fell down. He was dead.”

The Burroughs character provides Phillip an alibi for the murder. “Do you know what happened to you, Phil?” he says after hearing the confession. “You were attacked. Al attacked you. He tried to rape you. You lost your head. Everything went black. You hit him. He stumbled back and fell off the roof. You were in a panic.” Later, the Kerouac character gives Phillip a more precise defense: “Al was queer. He chased you over continents. He screwed up your life. The police will understand that.” And indeed, the police do believe his story of panic. The court sentences him to a few months in a mental hospital—a judgment that gives everyone around Phillip a bit of relief as the characters move on with their lives amid the heat of the New York summer.

“What will happen, I don’t know,” Kerouac wrote to his sister after sending off the manuscript to the publisher, adding, “For the kind of book it is—a portrait of the ‘lost’ segment of our generation, hardboiled, honest, and sensationally real—it is good, but we don’t know if those kinds of books are much in demand now.” Simon and Schuster passed on the manuscript, and Kerouac and Burroughs never did find a publisher for the book. The novel nonetheless betrays what the crime pages made certain—that claims of improper advances were often made up, and that the story of a queer man’s death was always partially his own fault.

The contrasting motives between these two retellings is notable. Ginsberg’s story reveals Carr’s homosexual panic, his repulsion at his own latent homosexual desires, as motivating the violent stabbing. For Kerouac and Burroughs, Carr’s defense is a consciously constructed fabrication for a seemingly motiveless crime.

What actually prompted Carr’s stabbing in Riverside Park that August remains a mystery. Once he completed his stay in Elmira, Carr kept his distance from the Beat circle and never talked publicly about the crime again. Perhaps Kammerer did accost Carr. Perhaps Carr, drunk and lacking self-control, had in fact finally exploded in a heat of anger and violence. Perhaps Carr’s violence was a repulsion against his own homosexual desires. “Like the rest of the University world, we are completely mystified at what happened,” the editors of the Columbia University student newspaper had written soon after the murder, adding, “There is a complexity to the background of the case that will defy ordinary police and legal investigations. The search for a motive will dig deep into the more hidden areas of the intellectual world.”

James Polchin has taught at the Princeton Writing Program, the Parsons School of Design, the New School for Public Engagement, and the Creative Nonfiction Foundation. A clinical professor at New York University, he lives in New York City with his husband, the photographer Greg Salvatori. Indecent Advances is his first book.

Adapted from Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall, by James Polchin. Used with permission from Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2019 by James Polchin.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ZTAkIS

Comments

Post a Comment