In the late seventies, well into his career as a writer and illustrator, Maurice Sendak began designing sets and costumes for the stage, including productions of The Magic Flute, The Nutcracker, and an opera adaptation of Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. Storyboards, sketches, and more from this relatively unheralded portion of his oeuvre comprise the exhibition “Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet,” which is on display at The Morgan Library and Museum through October 6. Fans of Sendak’s books will recognize in his theater designs the distinctive creatures and critters that haunt all his work, the unnerving but delightful processions they form, the mischief and wonder—and wildness—alive in their eyes. A selection of images from the show appears below.

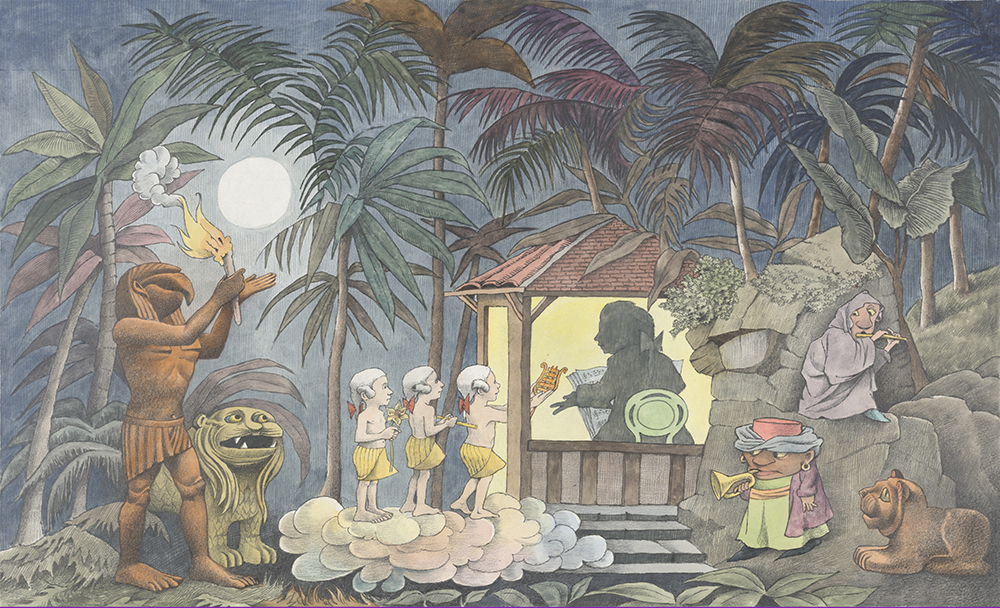

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Design for show scrim (The Magic Flute), 1979–1980, watercolor and graphite pencil on paper on board. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.104:120. Photo: Janny Chiu.

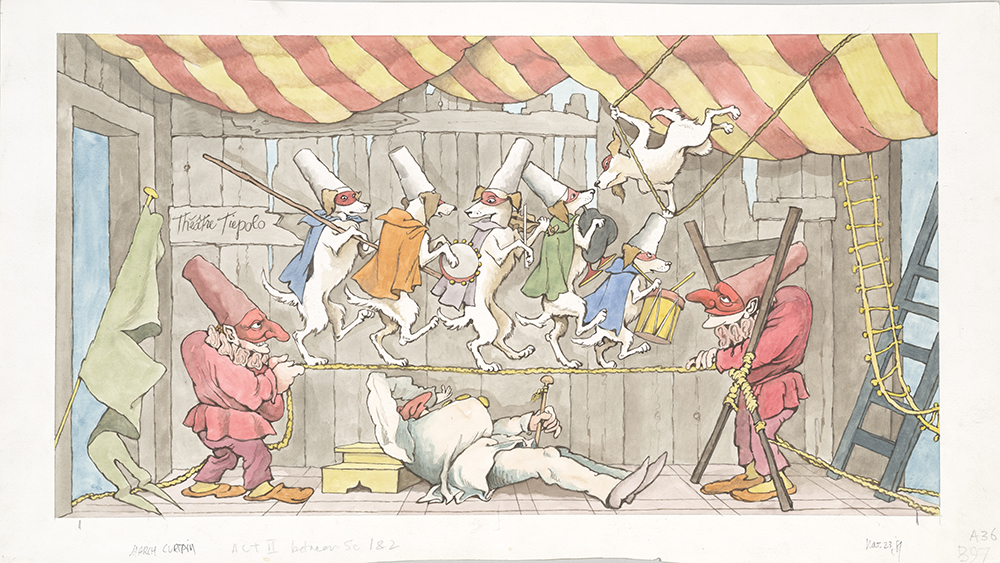

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Design for March curtain, Act II (The Love for Three Oranges), 1981, watercolor and graphite pencil on paper. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.106:166. Photo: Janny Chiu.

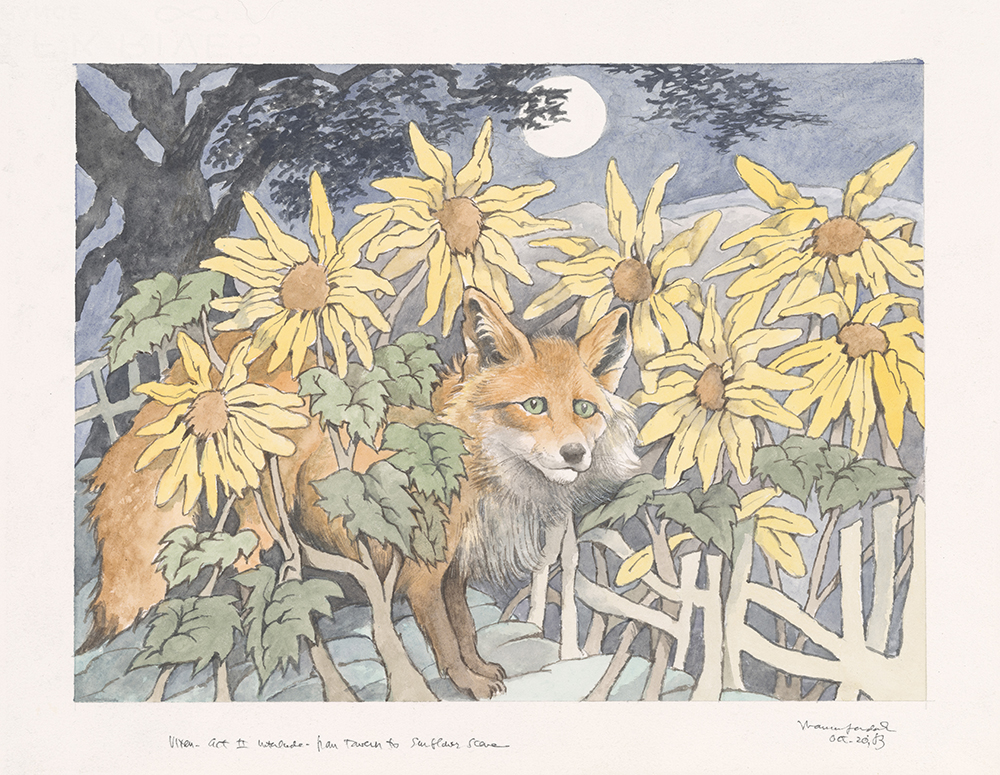

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), The Edge of the Forest, interlude between Act II, scenes 2 and 3, for PBS broadcast (The Cunning Little Vixen), 1983, watercolor and graphite pencil on paper. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.105:102. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Design for battle scene, Act I (Nutcracker), 1982–1983, gouache and graphite pencil on paper. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.107:262. Photo: Janny Chiu.

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), 5 Playing cards (The Love for Three Oranges), 1982, watercolor and pen and ink on laminated paperboard. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. Collection of Justin G. Schiller. Photo: Graham S. Haber, 2018.

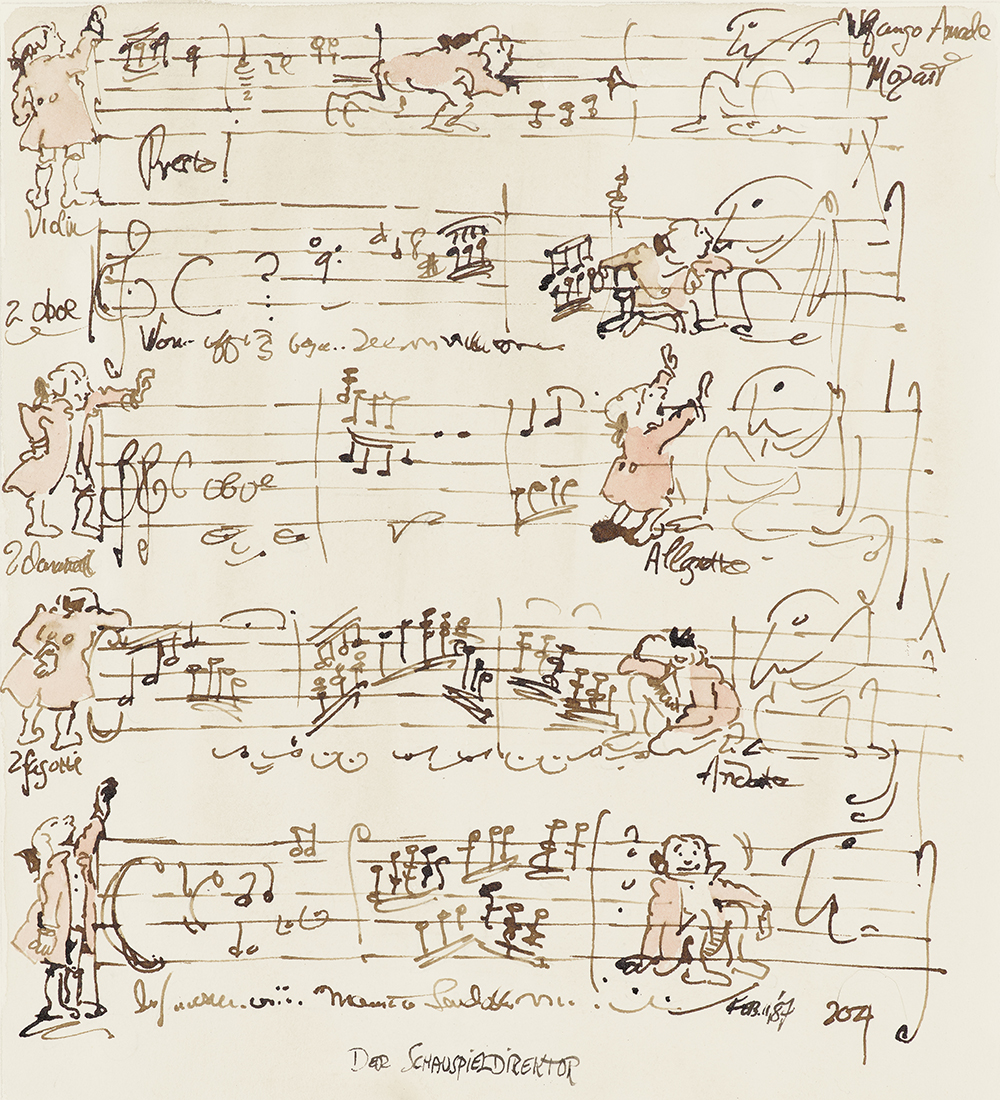

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Fantasy Sketch (Mozart, Der Schauspieldirektor), 1987, ink and watercolor on paper. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. Collection of the Maurice Sendak Foundation, Digital image courtesy of The Morgan Library and Museum. Photo: Graham S. Haber.

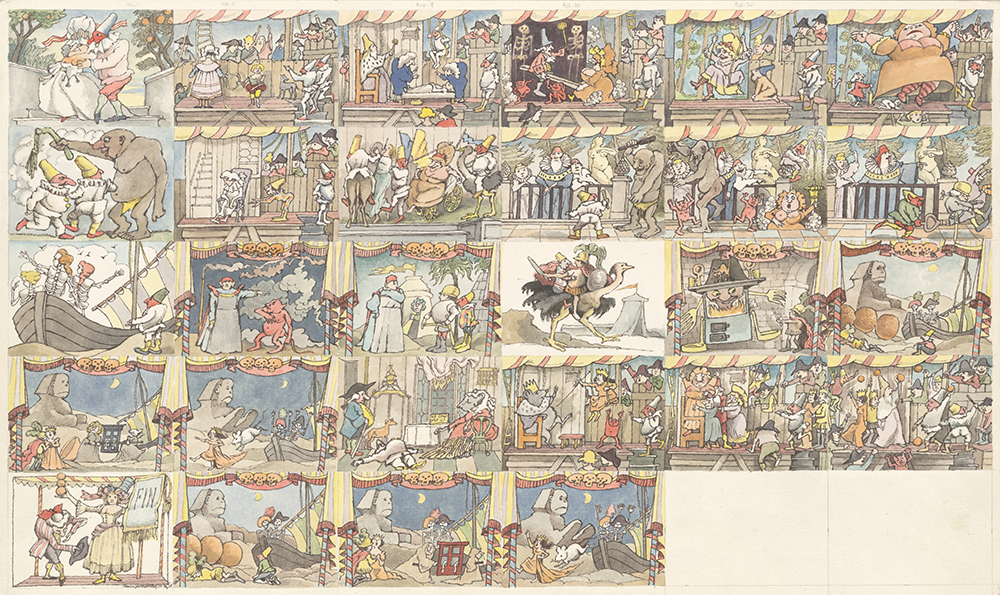

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Storyboard (The Love for Three Oranges), 1981–1982, watercolor, ink, and graphite pencil on board. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.106:169. Photo: Janny Chiu.

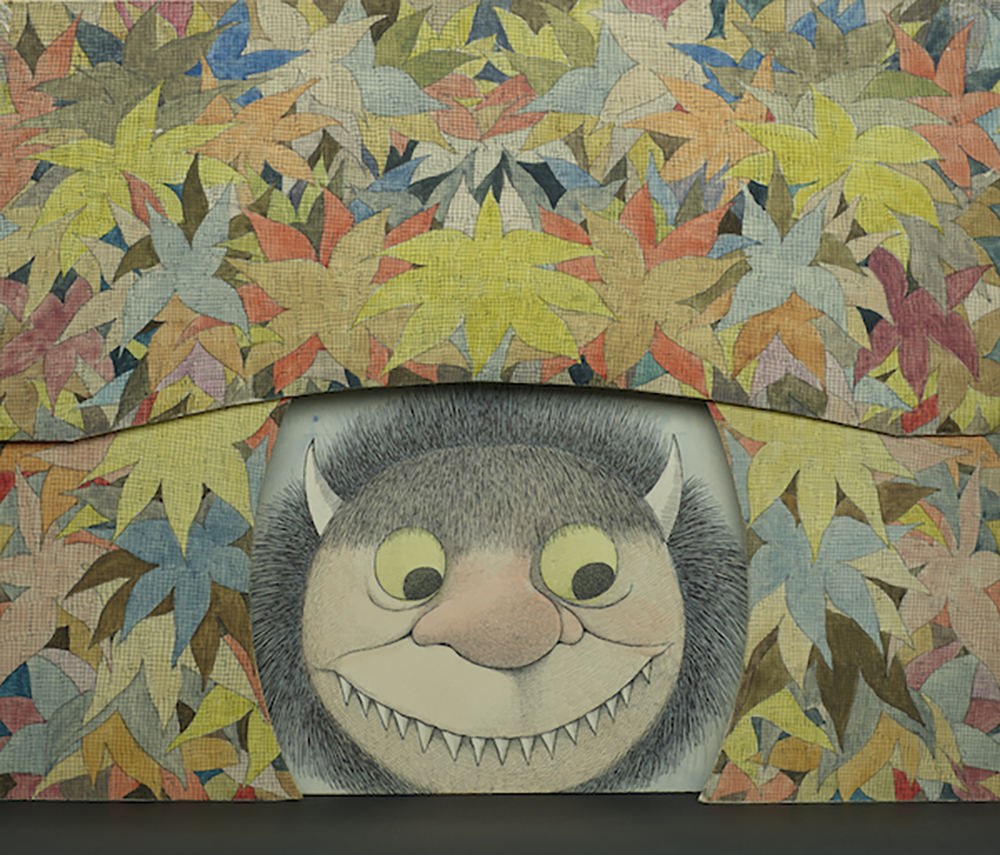

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012), Diorama of Moishe scrim and flower proscenium (Where the Wild Things Are), 1979–1983, watercolor, pen and ink, and graphite pencil on laminated paperboard. © The Maurice Sendak Foundation. The Morgan Library and Museum, Bequest of Maurice Sendak, 2013.103:69, 70, 71. Photo: Graham Haber, 2018.

“Drawing the Curtain: Maurice Sendak’s Designs for Opera and Ballet” is on view at The Morgan Library and Museum through October 6.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2MqE154

Comments

Post a Comment