Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

The Paris Review meets The New York Review of Books: our summer subscription deal continues! To celebrate, we’re taking a dive into both of our archives for this week’s Redux. Read on for Toni Morrison’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with her 2001 essay “On ‘The Radiance of the King’ ”; Mary McCarthy’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with her 1972 essay “A Guide to Exiles, Expatriates, and Internal Emigrés”; and Ernest Hemingway’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with George Plimpton’s 1980 speech reminiscing about this interview.

If you enjoy these free interviews and essays, why not subscribe to both magazines? From now through the end of August, you’ll pay just $99—35% off—to receive a yearlong subscription to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books, as well as complete access to their respective archives. And if you’re already a Paris Review subscriber, never fear—this deal will extend your current subscription, and your new subscription to The New York Review will begin immediately.

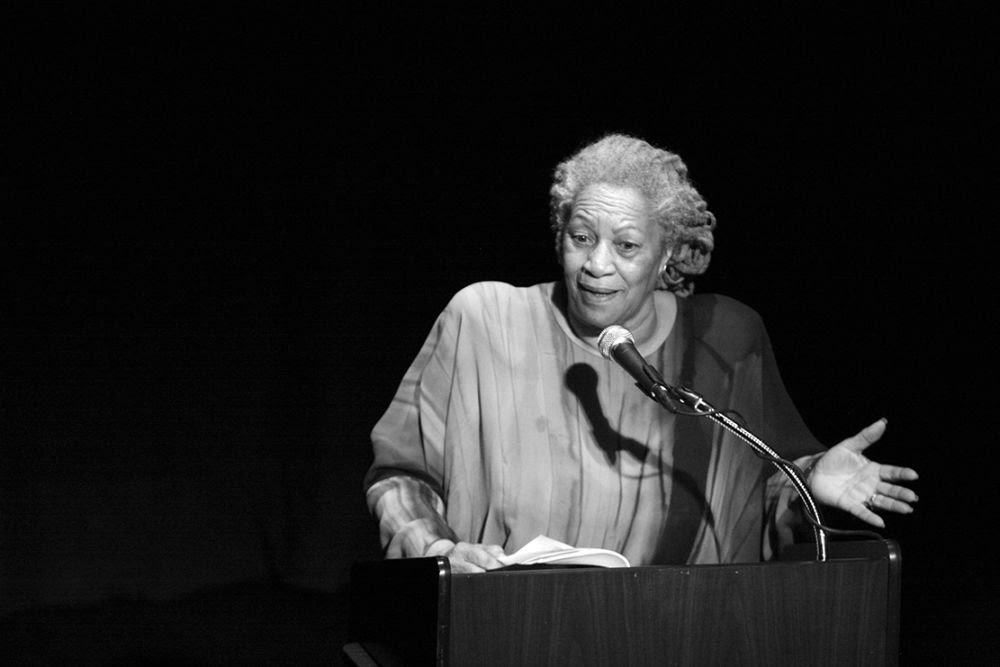

Toni Morrison, The Art of Fiction No. 134

The Paris Review, issue no. 128 (Fall 1993)

I don’t trust my writing that is not written, although I work very hard in subsequent revisions to remove the writerly-ness from it, to give it a combination of lyrical, standard, and colloquial language. To pull all these things together into something that I think is much more alive and representative. But I don’t trust something that occurs to me and then is spoken and transferred immediately to the page.

On ‘The Radiance of the King’

By Toni Morrison

The New York Review of Books, volume 48, no. 13 (August 9, 2001)

World War II was over before I sampled fiction set in Africa. Often brilliant, always fascinating, these narratives elaborated on the very mythology that accompanied those velvet plates floating between the pews.

Mary McCarthy, The Art of Fiction No. 27

The Paris Review, issue no. 27 (Winter–Spring 1962)

I’ve never liked the conventional conception of “style.” What’s confusing is that style usually means some form of fancy writing—when people say, oh yes, so and so’s such a “wonderful stylist.” But if one means by style the voice, the irreducible and always recognizable and alive thing, then of course style is really everything.

A Guide to Exiles, Expatriates, and Internal Emigrés

By Mary McCarthy

The New York Review of Books, volume 18, no. 4 (March 9, 1972)

More than anybody (except lovers), exiles are dependent on mail. A Greek writer friend in Paris was the only person I knew to suffer real pain during the events of May, 1968, when the mail was cut off. In the absence of news from Greece, i.e., political news, he was wasting away, somebody deprived of sustenance. They are also great readers of newspapers and collectors of clippings.

Ernest Hemingway, The Art of Fiction No. 21

The Paris Review, issue no. 18 (Spring 1958)

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write.

A Clean Well-Lighted Place

By George Plimpton

The New York Review of Books, volume 27, no. 20 (December 18, 1980)

Hemingway didn’t enjoy talking about writing. He felt it was a sort of draining operation, like drawing water from a well that wasn’t replenished that easily. So whenever I asked him a question about writing it was always with a faint wince that perhaps the response would be physical rather than verbal. It was like waving a match near the fuse of a bomb.

If you like what you read, subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2SRdAqn

Comments

Post a Comment