Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

The Paris Review meets The New York Review of Books: our summer subscription deal is here! To celebrate, we’re taking a dive into both our archives for this week’s Redux. Read on for Elizabeth Hardwick’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with her 1969 essay “Reflections on Fiction”; Susan Sontag’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with her essay on Simone Weil; and James Baldwin’s Art of Fiction interview, paired with his 1970 letter to Angela Davis.

If you enjoy these free interviews and essays, why not subscribe to both magazines? From now through the end of August, you’ll pay just $99—that’s 35% off—to receive a yearlong subscription to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books, as well as complete access to their respective archives. And if you’re already a Paris Review subscriber, never fear—this deal will extend your current subscription, and your new subscription to The New York Review will begin immediately.

Elizabeth Hardwick, The Art of Fiction No. 87

The Paris Review, issue no. 96 (Summer 1985)

I’m not sure I understand the process of writing. There is, I’m sure, something strange about imaginative concentration. The brain slowly begins to function in a different way, to make mysterious connections. Say, it is Monday, and you write a very bad draft, but if you keep trying, on Friday, words, phrases, appear almost unexpectedly. I don’t know why you can’t do it on Monday, or why I can’t. I’m the same person, no smarter, I have nothing more at hand.

Reflections on Fiction

By Elizabeth Hardwick

The New York Review of Books, volume 12, no. 3 (February 13, 1969)

The length of a novel, the abundance of detail have a disturbing and exciting effect on the imagination; in a sense one reads on to find out “what happens” and yet what happens is exactly the most quickly forgotten, the most elusive.

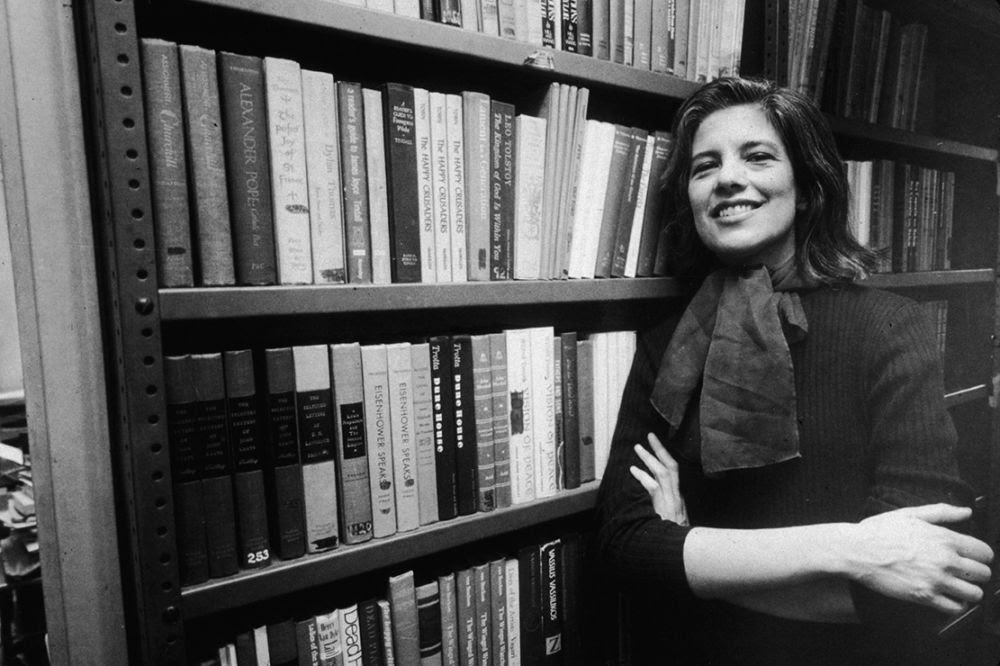

Susan Sontag, The Art of Fiction No. 143

The Paris Review, issue no. 137 (Winter 1995)

I wouldn’t be the person I am, I wouldn’t understand what I understand, were it not for certain books. I’m thinking of the great question of nineteenth-century Russian literature: how should one live? A novel worth reading is an education of the heart. It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.

Simone Weil

By Susan Sontag

The New York Review of Books, volume 1, no. 1 (February 1, 1963)

Ours is an age which consciously pursues health, and yet only believes in the reality of sickness. The truths we respect are those born of affliction. We measure truth in terms of the cost to the writer in suffering—rather than by the standard of an objective truth to which a writer’s words correspond. Each of our truths must have a martyr.

James Baldwin, The Art of Fiction No. 78

The Paris Review, issue no. 91 (Spring 1984)

When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway.

An Open Letter to My Sister, Miss Angela Davis

By James Baldwin

The New York Review of Books, volume 15, no. 12 (January 7, 1971)

One way of gauging a nation’s health, or of discerning what it really considers to be its interests—or to what extent it can be considered as a nation as distinguished from a coalition of special interests—is to examine those people it elects to represent or protect it.

If you like what you read, subscribe to both The Paris Review and The New York Review of Books for just $99.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2S901Cn

Comments

Post a Comment