In the summer of 1913, at 33 Fitzroy Square in London, the ornate Georgian house where the Pre-Raphaelites once gathered became the venue for another visionary artistic enterprise. Founded by the Bloomsbury painter and art critic Roger Fry, the Omega Workshops Ltd. was an interior decor and furniture company that sought to provide struggling artists with a regular income. “There is a certain social-class feeling, a vague idea that a man can still remain a gentleman if he paints bad pictures,” Fry observed, “but must forfeit the conventional right to his Esquire, if he makes good pots or serviceable furniture.” At the Omega, the distinction between fine and applied arts was dismissed. In the upstairs studio, fine artists designed colorful and original furniture, ceramics, textiles, and rugs, while downstairs two showrooms were open to the public, who could browse and purchase the wares. Fry, who coined the term post-Impressionism, wanted to energize fusty British homes with the French art movement’s vibrancy and brio. “It is time that the spirit of fun was introduced into furniture and into fabrics,” he declared. “We have suffered too long from the dull and the stupidly serious.”

At the Omega, Fry’s codirectors were two fellow Bloomsbury-ites, the artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. The trio were close friends and Bell, Virginia Woolf’s older, steelier sister, was romantically involved with Fry (typically for her circle, she had an open marriage). With her confident aesthetic judgement and dedication to personal freedom, Bell embodied the Omega ethos. Planning the launch party, she wrote to Fry: “We should get all your disreputable and some of your aristocratic friends to come and after dinner we should repair to Fitzroy Sq. where would be seen decorated furniture, painted walls etc. There we should all get drunk and dance and kiss. Orders would flow in and aristocrats would feel sure they were really in the thick of things.”

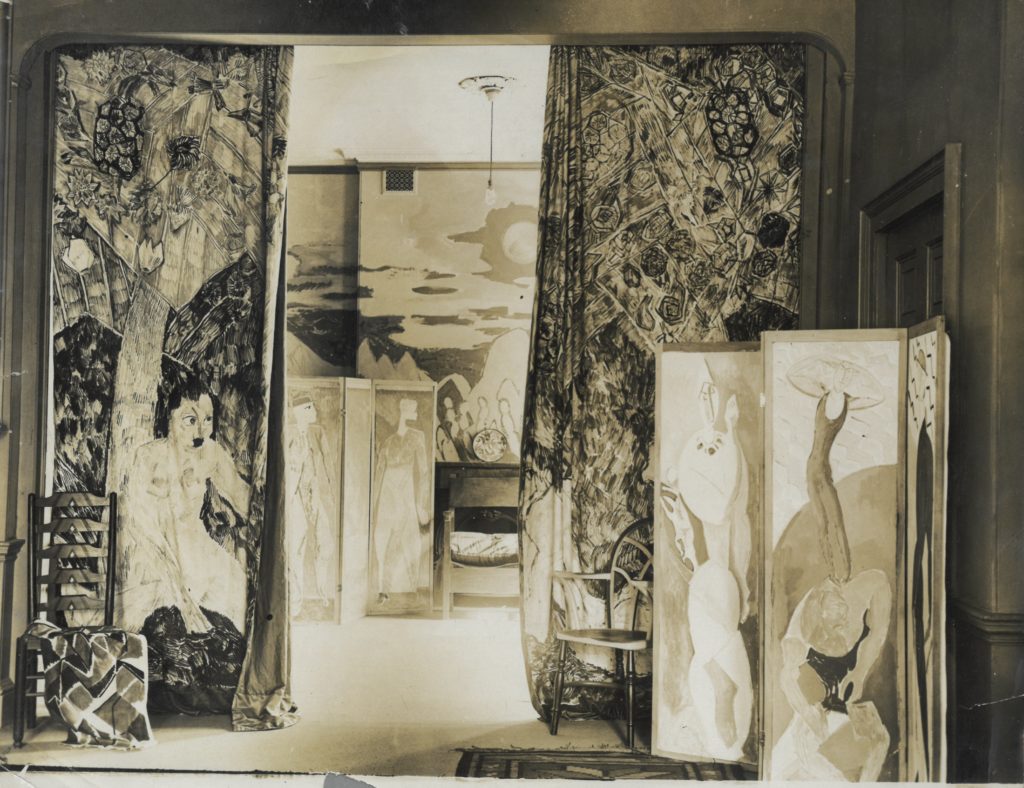

Design for Lalla Vandervelde’s Flat, 1916, Roger Fry. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The Omega had little trouble attracting upper-class women eager to revamp their homes in daring style. Clients included Princess Mechtilde Lichnowsky, the German Ambassadress with an eye for modern art, and the prolific hostess Lady Ottoline Morrell. Lady Ottoline, who was played by Tilda Swinton in the biopic Wittgenstein, was Fry’s lover for a time. He had to share her, alas, with Bertrand Russell and the painter Henry Lamb, not to mention her politician husband. “I was always a magnet for egotists,” she lamented. Another gregarious aristocrat, Lady Ian Hamilton, commissioned the Omega to help decorate several rooms in her home at Hyde Park Gardens. For a “Chinese room,” Fry designed a curved writing desk inlaid with marquetry birds, a matching stool, and a painted armchair. Bell was assigned a floral mosaic on the entrance hall floor, to be complemented by four original rugs and two stained-glass windows. The Hamiltons’ home was photographed for the weekly Sketch, which said: “the mistress of the house has mostly been her own designer and decorator and 1 Hyde Park Gardens is unique.”

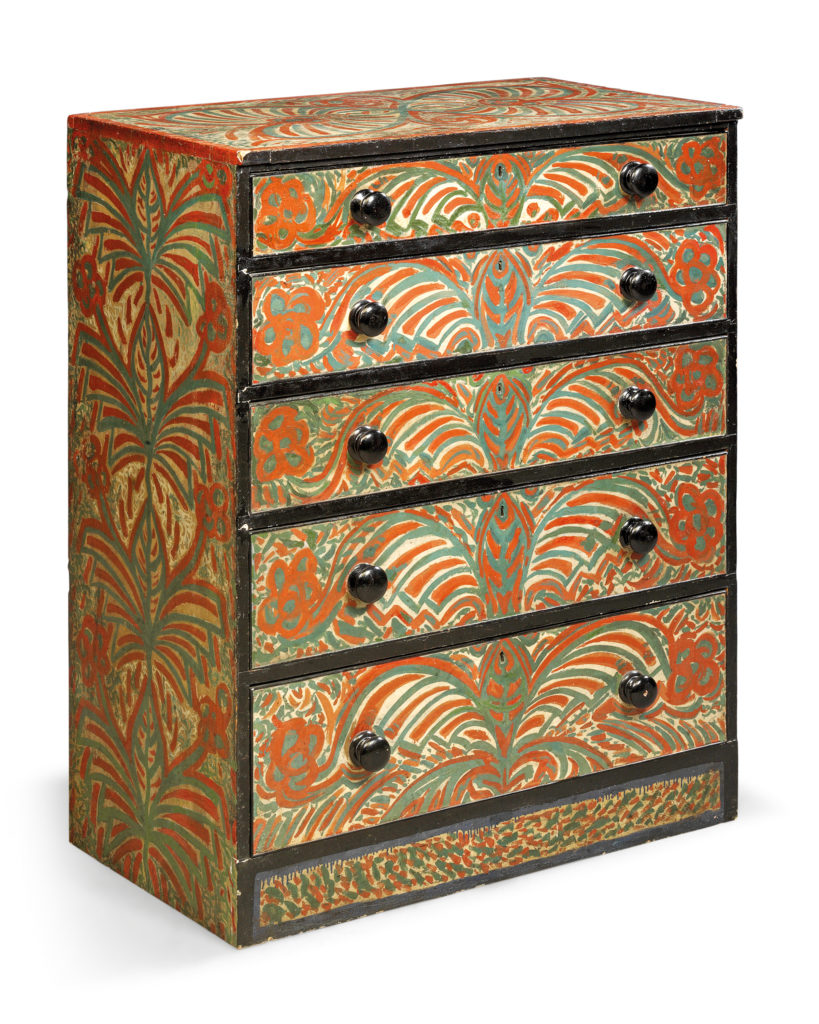

Chest of drawers, Roger Fry, c. 1919. Private Collection. Image © Christie’s Images and Bridgeman Images.

One of the rugs designed by Bell for Lady Hamilton, in pale wool with a striking triple-panel pattern of dark geometric lines, wouldn’t seem out of place in the most modern of twenty-first-century homes. It forms part of a fascinating exhibition that brings together an array of Omega objects—trays, screens, decorative boxes, lamps, textiles, and children’s toys—with design blueprints and paintings by (and of) Omega participants. Post-Impressionist Living: The Omega Workshops runs until January 19, 2020, at Charleston in East Sussex, the Bloomsbury Group’s storied country retreat. Alongside the galleries, the original sixteenth-century farmhouse is preserved just as it was during Bell and Grant’s residence. In the dining room, red-painted wood and cane chairs by Fry surround the lily pond table, Grant’s creation and one of the Omega’s most popular designs.

When the Omega opened, a Times reporter wrote that “what pleases us most about all the work of these artists is its gaiety. They seemed to have worked, not sadly or conscientiously upon some artistic principle, but because they enjoyed doing so.” The beautifully curated new show captures precisely this all-too-rare quality in design. Walking around the two large gallery spaces, you are struck by the sheer joy and levity infused into everything, from a round wooden tray inlaid with a cubist rendering of a woman riding an elephant, to a chest of drawers painted in a sea-green and orange art deco pattern of fanning curves and flowers. For the Omega artists, everything was a canvas and a chance to rebel against Edwardian formality. Fire screens are embroidered or painted with scenes evoking hotter climates, nude figures adorn plates, and fabrics are printed with vivid, post-Impressionist abstract designs. The exhibition’s immersive effect is less like stepping back a century than stepping out of time altogether, into a charmed realm of playfulness and heightened imagination.

While the design and decoration of many exhibits is credited to Fry, Bell, Grant, or other Omega artists such as Winifred Gill and Nina Hamnett, some are of uncertain or unknown attribution. Fry decreed that Omega work should be carried out anonymously, so that an atmosphere of communality was upheld and no individual artist attracted more attention,. Instead of being signed by the designer, the works bore the company insignia: the Greek letter Ω (Omega). Customers, Fry reasoned, would thus make unbiased decisions based on their own taste, rather than the artist’s renown. To ensure ample time for an artist’s own work, a maximum of three and a half days at the Omega was permitted. Hopeful employees often dropped by with portfolio in hand, but few were successful. Fry’s gentle formula of rejection was that a person’s work didn’t “interest” him. Courtesy was intrinsic to his personality, according to the art historian Kenneth Clark: “He never squashed or snubbed and would listen to the most preposterous suggestions with grave attention, ‘Oh, do you really think so?’”

Lampstands with geometric decoration, designed and made by the Omega Workshops, 1913-1919. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In the studio, young women—the “cropheads,” as Woolf called bob-haired art school graduates—tended to be saddled with more menial tasks, such as painting table legs and candlesticks. “When I remember Nina Hamnett at work,” Gill said, “it is always a candlestick she has in her hand.” Fry nevertheless praised his “lady artists” to a journalist, marveling that “many of them have very original and charming ideas.” And after Word War I began, their presence was more vital than ever. In October 1915, a photo feature in the Illustrated Sunday Herald showed Hamnett and Gill at work in “the futurist factory,” sewing, painting, and modeling Omega’s new line of bohemian floor-length dresses under the headline: “Women Who Do The Most Original War Work Of All.” The fashion department, led by Bell, succeeded in an otherwise lean time. “I confess I am surprised that people are still willing to spend money on things which one can’t call necessaries,” Fry wrote to his mother, “tho’ I’m glad enough for the sake of those who depend on the Omega.”

Plate with overglaze painted sailing boat design, Duncan Grant, 1913-14. © The Estate of Duncan Grant. All rights reserved. DACS 2019. The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The company survived the war, but only just. In June 1919, a closing-down sale was held, and everything was offered at half price. The event was immortalized by Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead Revisited; Charles Ryder decorates his room at Oxford with “a screen, painted by Roger Fry with a Provençal landscape, which I had bought inexpensively when the Omega Workshops were sold up.” By then, Bell and Grant were no longer involved in day-to-day operations. They had set up home at Charleston and, though Grant was mostly gay, had a child together. Yet for them both, as for many others, the Omega Workshops marked an epochal chapter. As an elderly man, Grant looked back on it as simply “the best period of my life.” Bell’s biographer Frances Spalding writes that working for the Omega “broadened Vanessa’s attitude towards painting … Shape, line and color now tumbled over the most ordinary object, weaving pattern and decoration into everyday life, releasing creative exuberance.”

Soon after the Omega closed, Fry went off to Provence, where he painted furiously and visited the former home of his patron saint, Cézanne. Woolf wrote to say that “the whole neighborhood of Fitzroy Square sounds a little bit dull and hollow, when that enormous vibration—your presence—is removed.” It would be another ninety years before one of English Heritage’s blue plaques, honoring Fry and the Omega Workshops, went up at 33 Fitzroy Square. Today, the house is available for hire as an event and meeting space, its rooms decorated and furnished with tasteful, chilly, neutral minimalism—a far cry indeed from when even the stately facade was graced with brightly colored canvases of dancing figures. “Marjorie Strachey thinks them hideous and that we shall be stopped by police,” Bell wrote to Fry as she worked on one, “but I can’t see what she means.”

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Lapham’s Quarterly Roundtable, Longreads, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, The Awl, Words without Borders, and other publications. Read her Feminize Your Canon column for The Paris Review Daily here.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2lvGS1S

Comments

Post a Comment