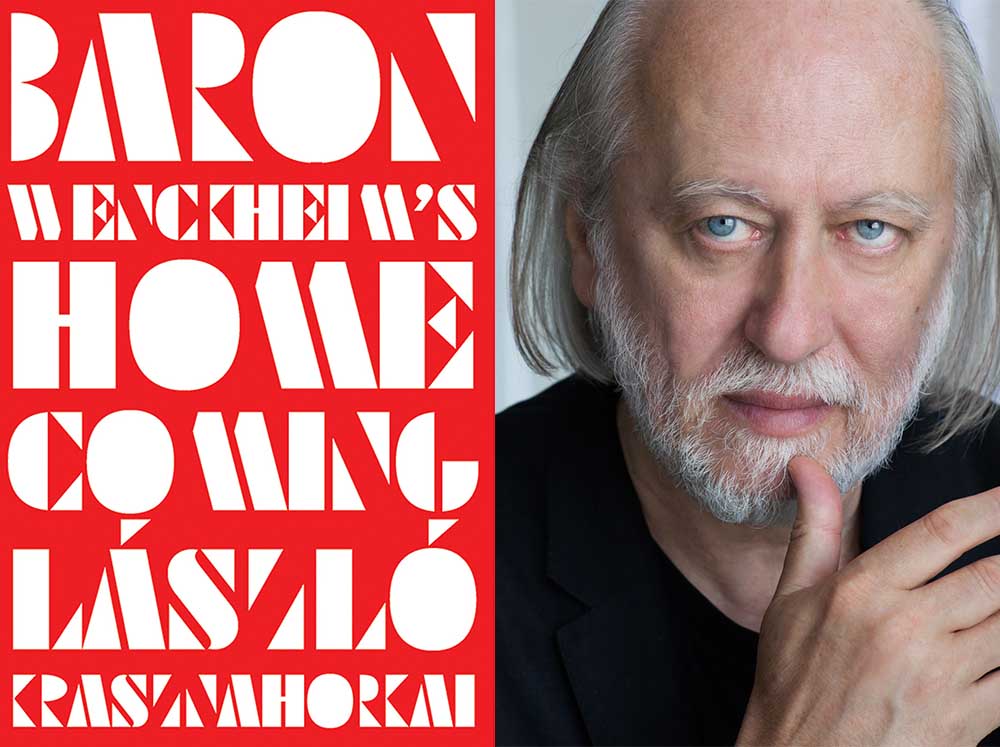

Read our Art of Fiction interview with László Krasznahorkai in the Summer 2018 issue

The playful, pessimistic fictions of the Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai emit a recognizably entropic music. His novels—equal parts artful attenuation and digressive deluge—suggest a Beckettian impulse overwhelmed by obsessive proclivities. The epic length of a Krasznahorkai sentence slowly erodes its own reality, clause by scouring clause, until at last it releases the terrible darkness harbored at its core. Many of his literary signatures—compulsive monologue, apocalyptic egress, terminal gloom—are recognizably Late Modern. But the extravagant disintegration and sly mischief of the work make him difficult to mistake for anyone else. There are the sudden, demonic accelerations; the extraordinary leaps in intensity; the gorgeous derangements of consciousness; the muddy villages of Mitteleuropa; the abyssal laughter; the pervasive sense of a choleric god waiting patiently just offstage. Here is fiction that collapses into minute strangeness and explodes into vast cosmology. It is, as Michael Hofmann says of Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, “more world than product,” a planetary concretion of energy and motion, and subject to its own eventual heat death.

Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming is the latest Krasznahorkai novel to reach English readers, in a typically extraordinary translation from Ottilie Mulzet. It represents, as the author recently told The Paris Review in his Art of Fiction interview, the conclusion of a tetralogy:

I’ve said it a thousand times that I always wanted to write just one book. I wasn’t satisfied with the first, and that’s why I wrote the second. I wasn’t satisfied with the second, so I wrote the third, and so on. Now, with Baron, I can close this story. With this novel I can prove that I really wrote just one book in my life. This is the book—Satantango, Melancholy, War and War, and Baron. This is my one book.

Four books that make up one book, then; a kind of purgatorial gestalt. Baron Wenckheim absorbs energies from these other novels. (It is there in the title, the child Estike having poisoned herself on the grounds of Wenckheim Castle in Satantango.) The eponymous protagonist is the latest in Krasznahorkai’s long line of Myshkin-like innocents, beings of great purity who nonetheless hasten death and destruction. The baron returns to the small Hungarian town of his birth, fleeing enormous gambling debts accrued in Argentina. Learning of his imminent arrival, the hamlet’s inhabitants plan a welcome parade, hoping to extract from him whatever wealth remains. Bureaucrats and dignitaries scheme alongside criminal bikers and con men. But the Baron—shy, retiring, unremittingly terrified—seeks only Marika, the teenage sweetheart who spurned him decades prior. Meanwhile, across town, in an abandoned hut, a hermit known only as the Professor (the world’s foremost expert on mosses, incidentally) proceeds with the exercises he believes will forever eradicate thought from his mind.

Ascribing Krasznahorkai’s allure to plot is rarely fruitful; at best, the events are an armature over which the thickened material of consciousness can drape and flow. (Another of Krasznahorkai’s translators, the poet George Szirtes, has described his work as “a vast black river of type.”) The great paradox of his fiction is that the speed and intensity of its sentences suggests a seething, maximalist vision—something like the untrammeled surplus of Thomas Bernhard, or the aesthetic excess of José Lezama Lima—though what actually happens is quite modest in terms of developed incident. The novel’s momentum is circumscribed by chaotic inwardness. Characters generate and exhaust meaning in lush pauses. A mysterious sense of contingency reigns. Krasznahorkai’s conception of inner life seems, finally, a form of negative witness. The communicable becomes as mysterious—as elusive—as divinity itself.

Mental or spiritual unraveling often precedes apocalyptic action in Krasznahorkai. The Professor, on the lam after shooting one of the biker gang’s lieutenants in self-defense, fakes his own death and flees town. Before disappearing entirely from the novel, he delivers a final frenzied monologue, the exit music of madness. “In vain is the endeavor to annihilate thought,” he says, “the consistent, dreadful, awful, the rigorous attention with which we must continuously prevent ourselves from arriving at some result in thinking.” The wonderful paradox of his thought-killing exercises is that they in fact produce endless waves of foaming cognition. In just a few pages, he touches on the concept of the infinite, fear as the birth of culture, the cowardice of atheism, and the pervasiveness of human illusion. “The world is nothing more than an event, lunacy, a lunacy of billions and billions of events,” he continues, “and nothing is fixed, nothing is confined, nothing graspable, everything slips away if we want to clutch onto it.” Eventually he alights on a fragment from the Hungarian poet Attila József: “Like a pile of hewn timber / the world lies heaped upon itself.” Its aphoristic elegance fascinates the Professor and provides, at last, a moment of exquisite cooling amid the molten flow of his thoughts.

Meanwhile, the Baron’s long-awaited homecoming is spoiled not by the obsequious avarice of the townspeople but by the corrosions of memory: “Nothing remained from the world that had been here … these were not the same train stations, main roads, hospitals, castles, or chateaus, they just happened to stand in exactly the same spot where the old ones used to be.” He refuses social obligations, embarrasses himself in front Marika (whom he doesn’t seem to recognize), and finally undergoes a kind of spiritual trial—should he live or destroy himself?—during a moonlit walk along a forest railway:

It wasn’t the weight—because what kind of weight could a question like this have before the Good Lord, who was so, but so pestered by other questions—but that there wasn’t even any question, or that his question was completely meaningless, because his questions—why did he have to live, and so forth—simply wasn’t a question, but was itself the answer, this was the answer to his question, thought the Baron, his question was the answer.

Something of Dostoyevsky surfaces here, a writer Krasznahorkai admires. The baron achieves, in his final moments, the ragged grandeur of a Karamazov, vexed, plangent, at odds with fate. His accidental destruction sets in motion the novel’s apocalyptic finale, in which a figure who may or may not be the Antichrist conjures a holocaust of cleansing flame, incinerating the town and its sordid inhabitants.

This summary still leaves out a great deal: the bumbling mayor, the vicious and sentimental leader, poor Marika, the con artist Dante, the Professor’s engaging Little Mutt, a cameo from the Pope, The Real World (season two), and the mysterious Idiot Child, to say nothing of the town’s beggars, horses, priests, and speckled deer. (A nearly complete list of every person, object, and animal missing or destroyed is provided in an index.) This overabundance is symptomatic of the rarely discussed generosity of Krasznahorkai’s vision. His fiction’s recursive darkness can obscure its ambiguous grace. It makes space for everything human, which is to say even—and perhaps especially—the inhuman and the frankly monstrous. This is not hysterical realism but the triumph of excess in all its startling, gravid particularity.

Baron Wenkcheim’s Homecoming is a fitting capstone to Krasznahorkai’s tetralogy, one of the supreme achievements of contemporary literature. Now seems as good a time as any to name him among our greatest living novelists. “What is worthwhile to deal with,” the Professor says, “is this: the yeses, with the demonstrables, with positive declarations, designations, expansions, displacement, reflection, meaning-amplification, and transference.” Affirmation is embedded in every negation. A Krasznahorkai novel may be an abyss, but the depths are brimming.

Read our Art of Fiction interview with László Krasznahorkai in the Summer 2018 issue

Dustin Illingworth is a writer in Southern California.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/34VaeZ0

Comments

Post a Comment