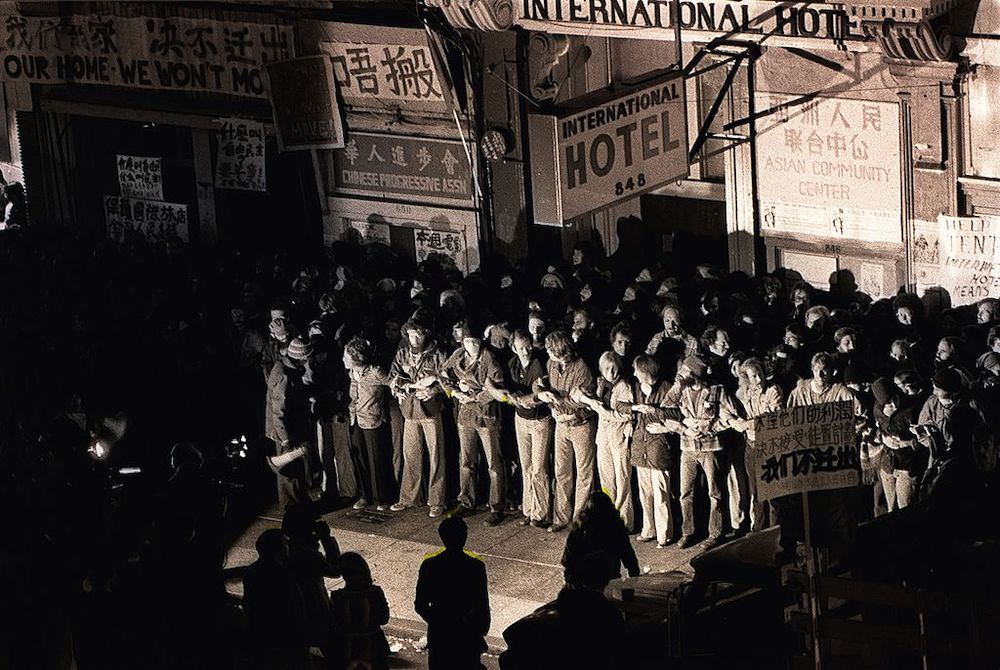

Protesters link arms in front of the International Hotel in San Francisco in an attempt to prevent the police from evicting elderly tenants on August 4, 1977. Photo: Nancy Wong. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Imagine that you’re a sullen, sheltered kid from Manila who thinks she knows everything there is to know about the United States of America. But as soon as you and your broken family land in San Francisco, life slaps you hard in the face. Did you emigrate or immigrate? You don’t know. Are you mestiza or brown? You don’t know. In fact, you realize you don’t know anything.

Your first year in America, John F. Kennedy is assassinated. Five years later, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. War rages in Vietnam and on television. You are reminded of the Philippines every time you see footage of Vietnam in flames. The universe is shrinking right before your very eyes. Marvin Gaye croons “What’s Going On” and breaks your heart.

Mother, mother

There’s too many of you crying

Brother, brother, brother

There’s far too many of you dying

KSOL! KSAN! KJAZ! It’s funky glorious scary druggy 1972. Martial law has been declared in the Philippines, Angela Davis has finally been released from prison, and Salvador Allende has not yet been assassinated in Chile.

Who and what and where are your people?

You dance to the Temptations singing “Ball of Confusion.”

People movin’ out

People movin’ in

Why, because of the color of their skin

Run, run, run, but you sure can’t hide

It’s the perfect theme song for the fall of the International Hotel, for the brutal eviction of the elderly Filipino and Chinese tenants who lived there, and for what eventually happened to San Francisco, a place once hailed as the City of Poets.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

In funky glorious scary druggy 1972, you encounter a Filipino activist-shaman-poet with twinkly eyes and an intense way of talking named Al Robles.

Poetry workshop happenin’ in the basement of the I-Hotel, Sister! And it’s free! Come to Manilatown, write poems, drink wine, eat some adobo and rice!

The I-Hotel? Manilatown? What Manilatown?

Right there on Kearny Street, in the shadow of Chinatown.

You are speechless. Al is stunned by your ignorance.

Sister, you mean you been here since 1963 and don’t know nothin’ ’bout Manilatown or Kearny Street Workshop or the I-Hotel?

So off you went, in search of poetry and self.

*

I for international, I for intellectual. I for the eternal hungry i. I for Tino’s Barbershop, I for Benny’s Cigar Store. I for Bataan Drugstore, Bataan Pool Hall, Bataan Restaurant. I for Mike’s Pool Hall. Santa Maria Restaurant. I for Manilatown Manongs. Kearny Street. Jackson Street. Chinatown. Sam Wo Restaurant. Edsel Ford Fung. No booze, no jive, no fortune cookies. Portsmouth Square. Not enough money, not enough sun. SRO. Fluorescent lights. Too much life piled into closet-size rooms. I-Hotel. Home, baby.

*

Karen Tei Yamashita’s I Hotel is a big, bold beast of a book. Genre-defying, trippy, brilliant. With a lot to say about the Bay Area in the tumultuous seventies and a lot to say about political movements, community building, activism, and art. Originally published in 2010 by Coffee House Press, I Hotel was critically lauded and nominated for the National Book Award in fiction. But “fiction” doesn’t quite cut it. Call it a meta meta metaphor, part fiction and part fact, an immersive theatrical experience, a space-jazz-rock-funk opera, or all of the above. I Hotel’s pleasures and provocations are abundant. Gritty cartoons, deliberately corny puns, manifestos, transcripts, dossiers, history, philosophy, audio transcripts, poetry, song lyrics, aphorisms, excerpted film scripts, and play scripts make up this playful, meticulously researched and constructed literary work. Narrators shift from the lonesome I to the inclusive we in a heartbeat. Black Power. Black Panther. Brown Power. Yellow Power. Red Power. Red Guard. Makibaka! Huwag matakot. Kalayaan. Freedom now. Coalitions. Movements galore. Third World dis and Third World dat. Identity. Community. Communiqué. Who am I? And what, exactly, does it mean to be Asian American? Karen Tei Yamashita explores these questions and conflicts with verve and a keen sense of the theatrical and the absurd.

I Hotel begins and ends with tragedy. It opens on Lunar New Year in 1968 with the Tet Offensive happening. In San Francisco, the father of a teenage boy suddenly collapses and dies on a street in Chinatown. Crackle and pop of incessant firecrackers. The smell of smoke. The mood is festive and violent. The end comes in the early morning hours of August 4, 1977. Three hundred cops in full riot gear beat back thousands of protesters and get busy evicting the fifty remaining tenants—many frail and in their eighties—from the International Hotel. Overkill, for sure.

Fast forward to 2019. The New York Times gloats: “Thousands of New Millionaires [Are] About to Eat San Francisco Alive.” Another headline, a few weeks later: “In San Francisco, Making a Living From Your Billionaire Neighbor’s Trash.” The full-time trash picker is a military veteran named Jake Orta. The billionaire neighbor is Mark Zuckerberg.

Because of its scope and ambition as well as the decade it chronicles, I Hotel makes me think of dazzling, adventurous works from the sixties and seventies: Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics, Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch, and the percussionist-composer Stomu Yamash’ta’s Red Buddha Theatre production of The Man from the East.

In these dark times of planetary crisis, sinister algorithms, and yammering despots, Karen Tei Yamashita’s mythic I Hotel seems more relevant than ever. Mabuhay to Coffee House Press for reissuing this book.

Jessica Hagedorn was born and raised in the Philippines and came to the United States in her early teens. Her novels include Toxicology, Dream Jungle, The Gangster of Love, and Dogeaters, winner of the American Book Award and a finalist for the National Book Award. Hagedorn is also the author of Danger and Beauty, a collection of poetry and prose, and the editor of three anthologies. She is working on a musical play about the pioneering all-female rock band Fanny.

Used by permission from I Hotel (Coffee House Press, 2019). Copyright © 2019 by Jessica Hagedorn.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2qlWCWZ

Comments

Post a Comment