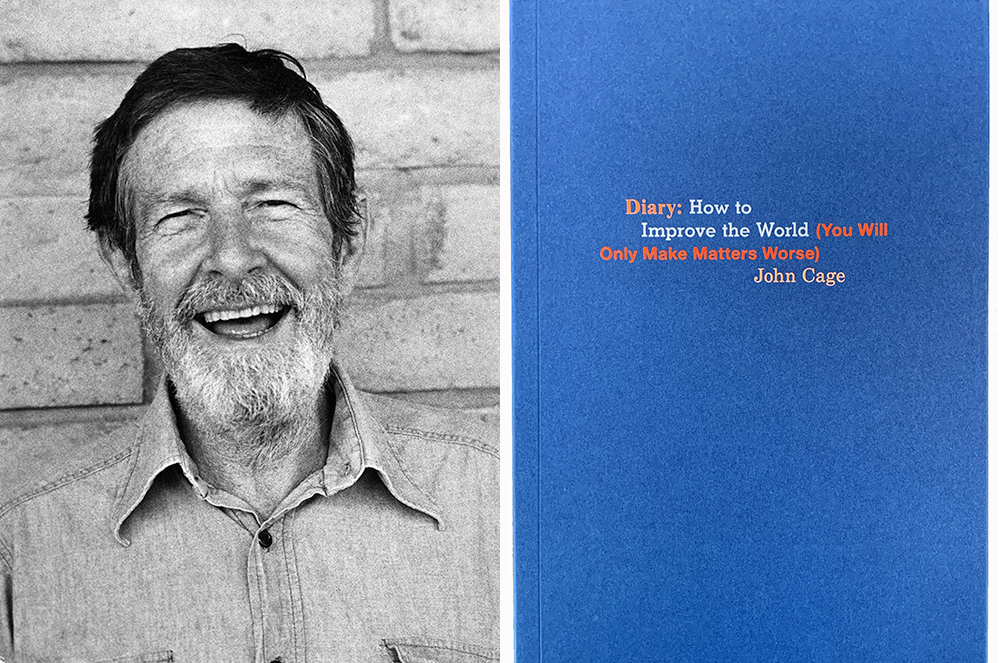

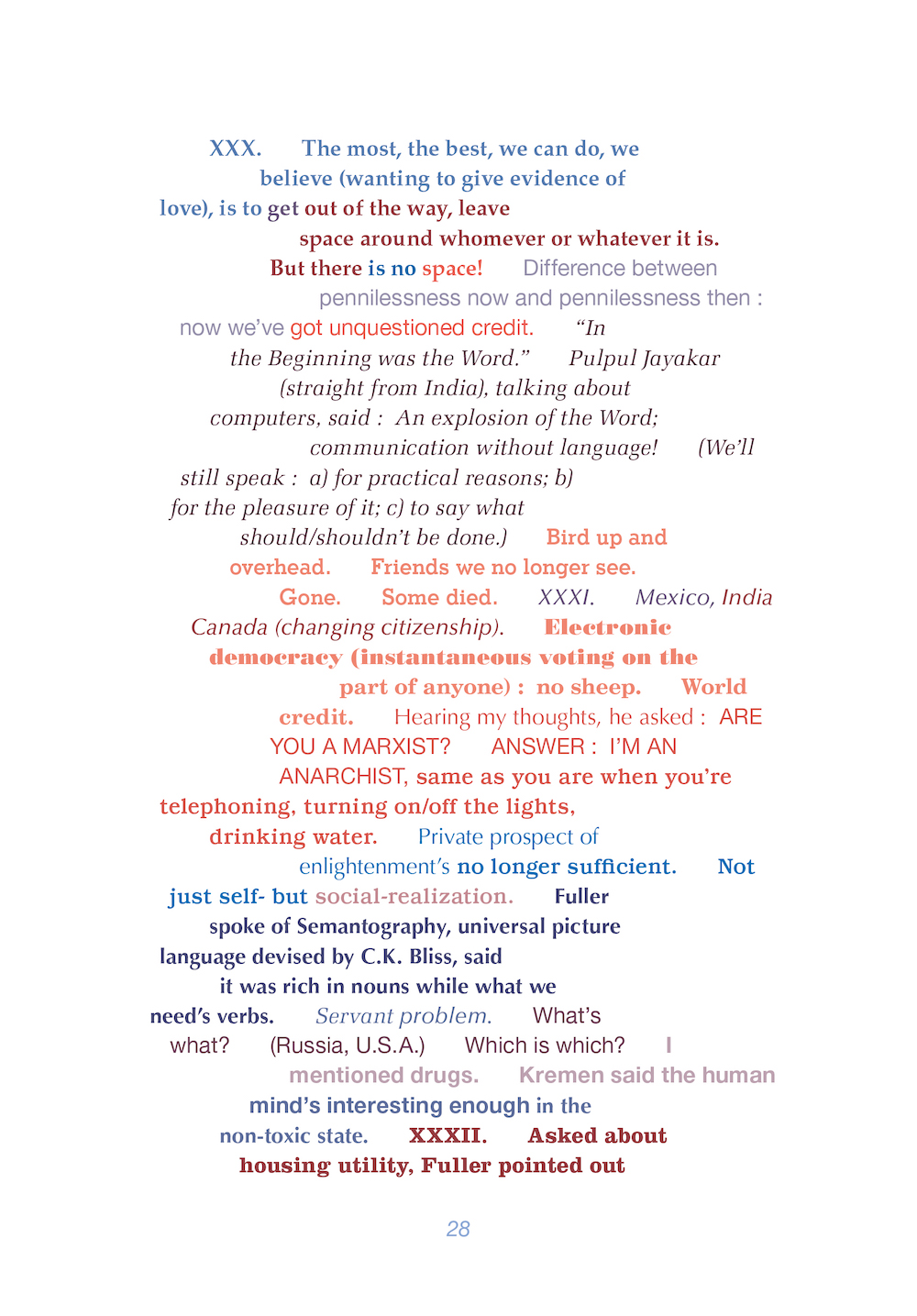

To put it mildly, John Cage’s Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) is no ordinary account of days gone by; a plain record of events would be too simple for such a daring and meticulous artist. The product of thirty years, Diary allows us a glimpse of the late twentieth century through Cage’s eyes. His insights and observations reveal a generous, openhearted view of the world in tumult. In keeping with this openness is the book’s methodology: using a number generator based on the I Ching, Cage would allow chance to determine each entry’s word count, left margination, and typeface. Like much of Cage’s oeuvre, the complexity of this process melts away in the experience of the work. Here, for instance, is the first page of Part II, which was originally published in the Winter–Spring 1967 issue of The Paris Review:

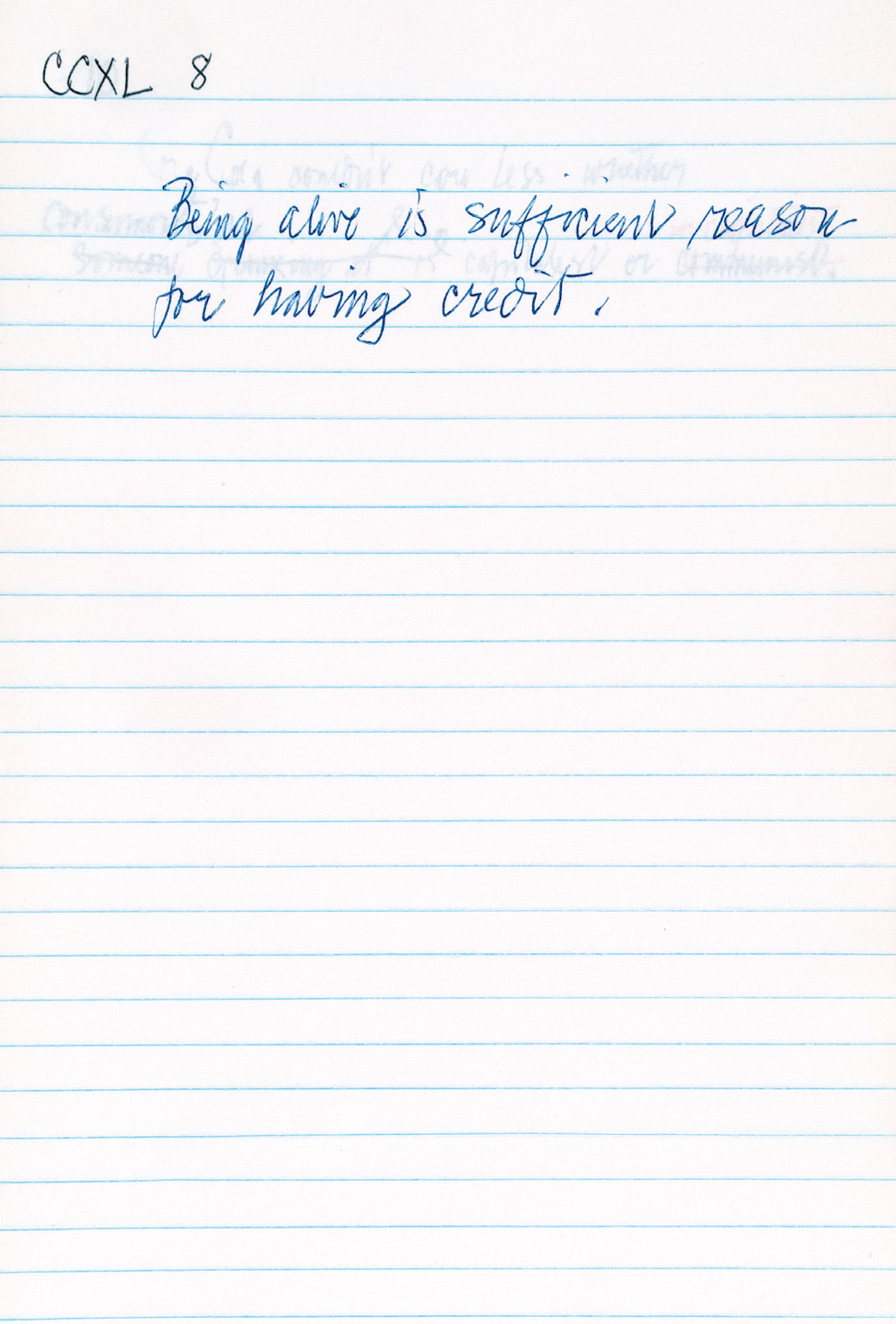

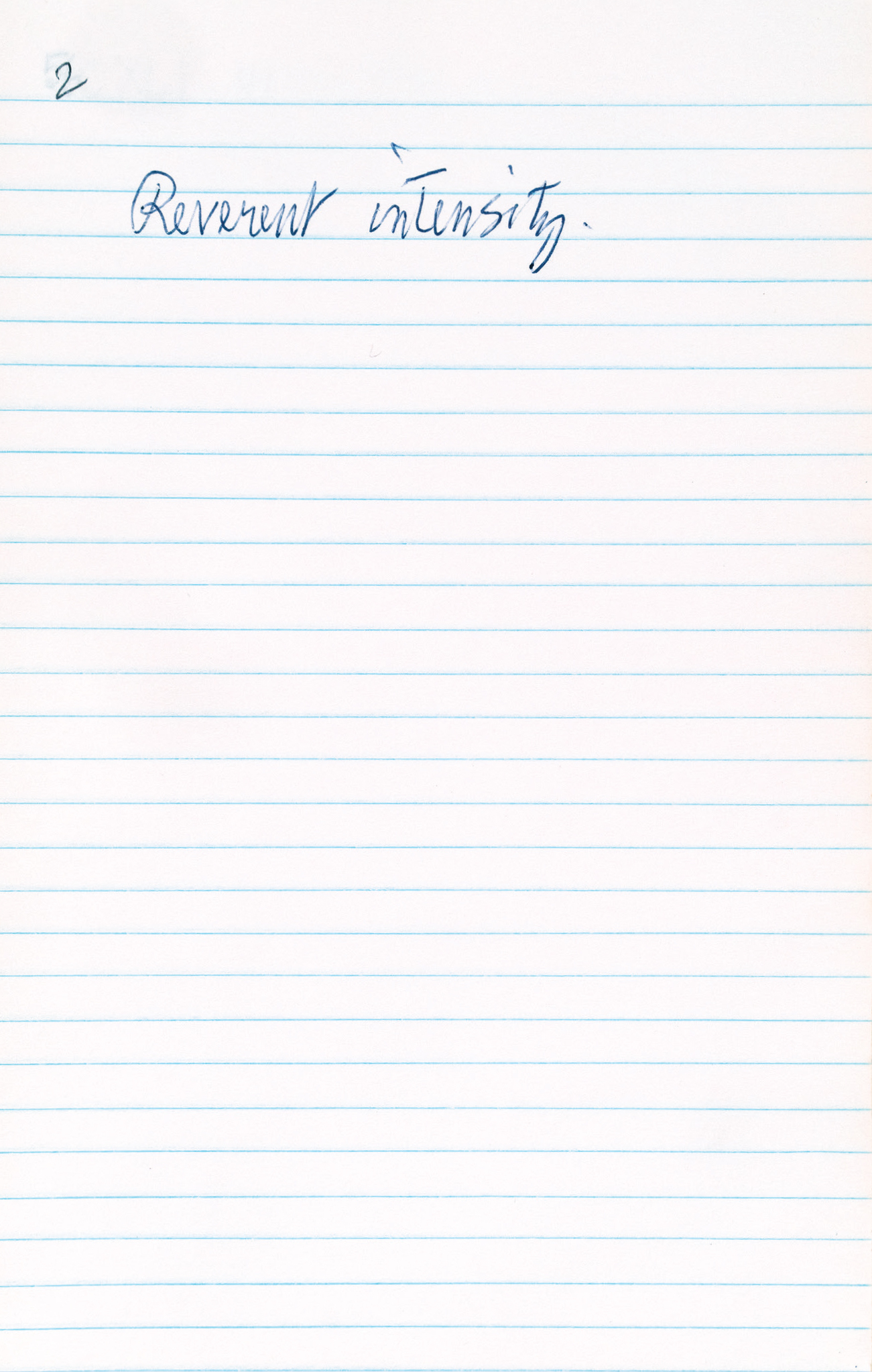

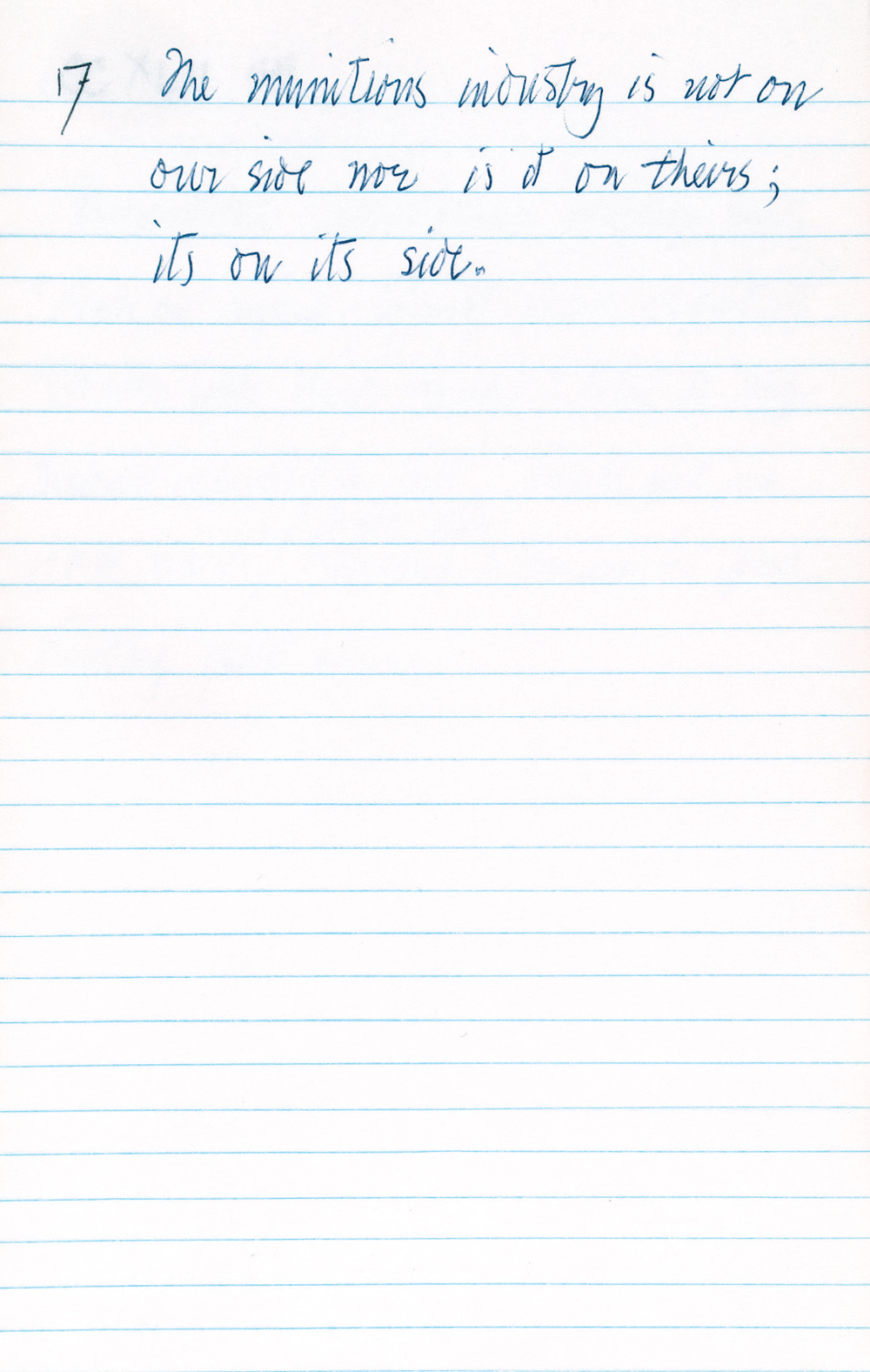

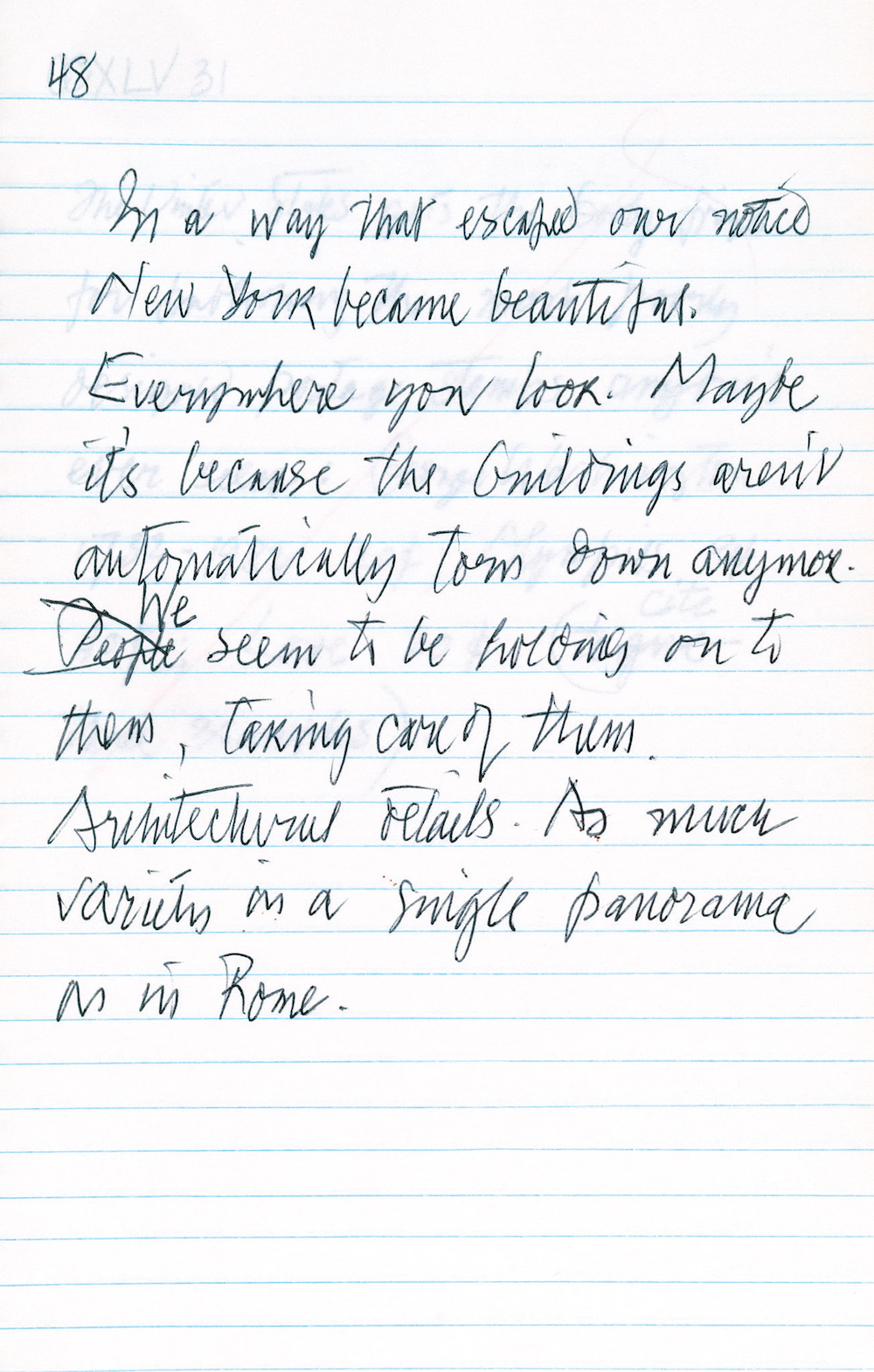

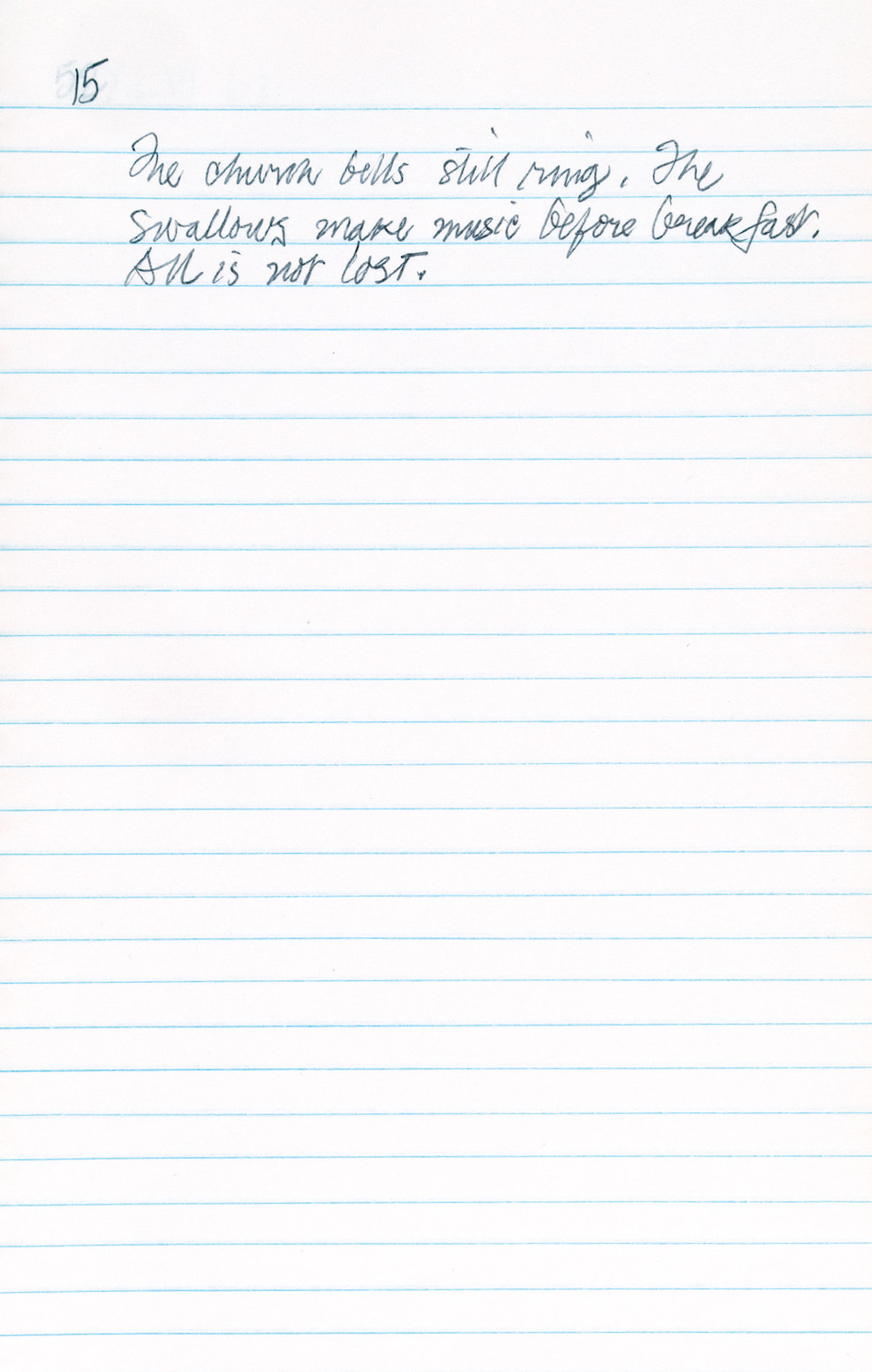

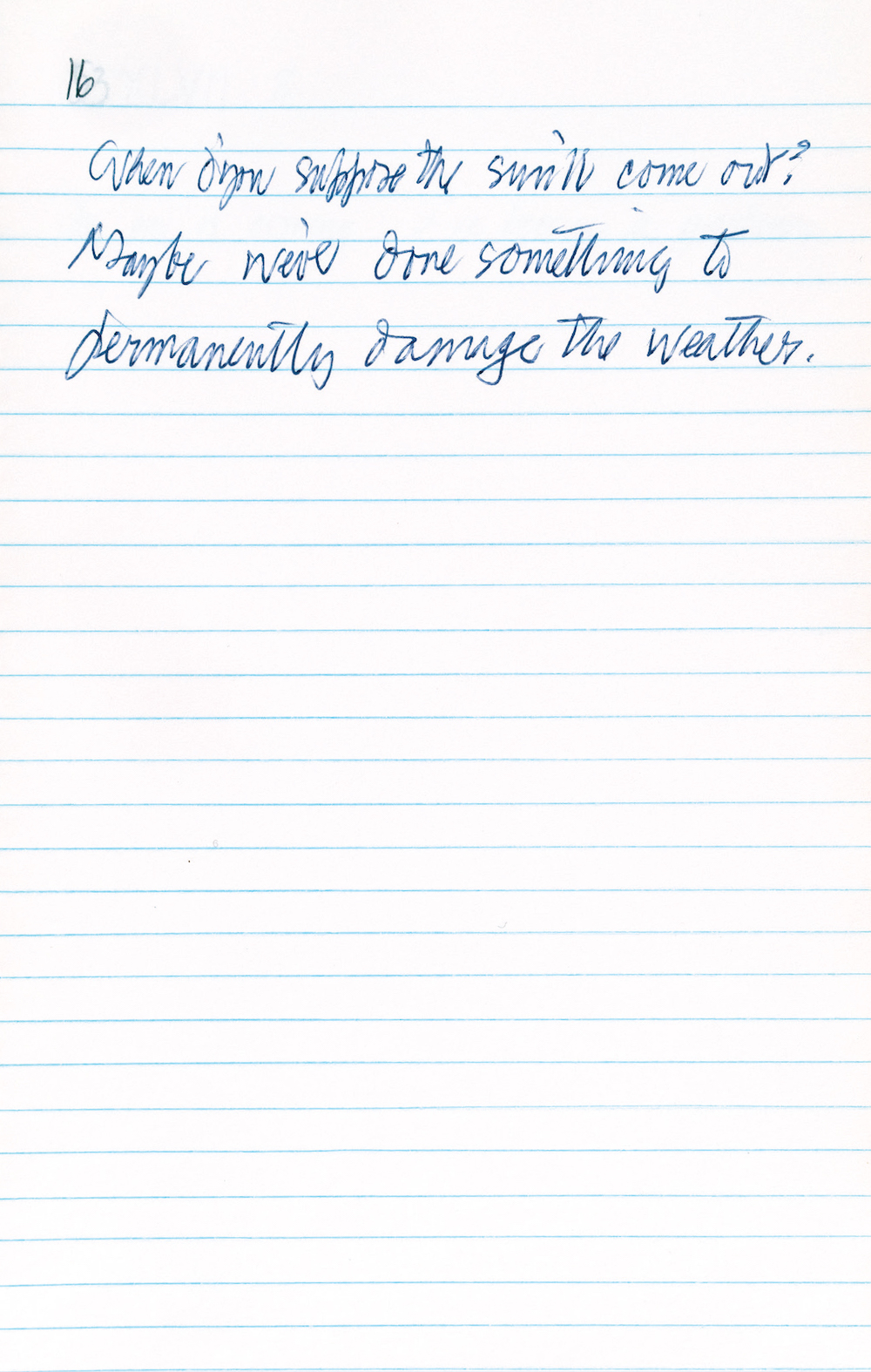

At first glance, it scans as chaos. In practice, it reads like poetry, though the typographical pyrotechnics lend it a unique tactility, as though the letters are swelling off the page. In 2015, Diary appeared in a single volume for the first time, published by Siglio Press. A new paperback version has just been released, now with a selection of pages from the unpublished ninth installment in Cage’s project (he had planned ten parts in all but completed only eight by the time of his death, in 1992). Six facsimile pages from Cage’s notebooks appear below.

All images from Diary: How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse), by John Cage, published by Siglio Press.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2WxVMT9

Comments

Post a Comment