Nick Tosches, music writer and biographer, died at the age of sixty-nine on Sunday.

I spent an awful lot of time around Nick Tosches in the late seventies. We’d wind up in the same places, we were published in the same crummy magazines, and we’d stumble into each other at St. Mark’s Bookshop or the Bells of Hell or Gem Spa. It was always midnight, and he almost always had a book in his pocket, maybe The Twelve Caesars or Ovid, and a wrestling magazine.

I lost touch with him, but kept up with his writing, or tried to. After Hellfire and Dino and a few other astonishing books, his prose got overheated, but somehow undercooked. He’d throw a handful of twenty-dollar words and twenty-five-cent ideas up in the air, sort of hoping they’d take wing, but if they didn’t, he’d get bored and just watch them tumble to the ground, stare at them sadly, kick a few over to see if they were still breathing, then wander off to get a smoke.

Though he wrote some of the best and most evocative books on music, his real gift was for rooting around the back rooms, the hustles, the shadows and the half-truths that make up the underbelly of show business. If the devil was in the details, he was perfectly happy to dig through the devil’s briefcase and read the fine print of the love letters and girlie magazines he found inside. He was part accountant, part private eye, part stumblebum, but his passion was contagious, and he always listened to the B-sides.

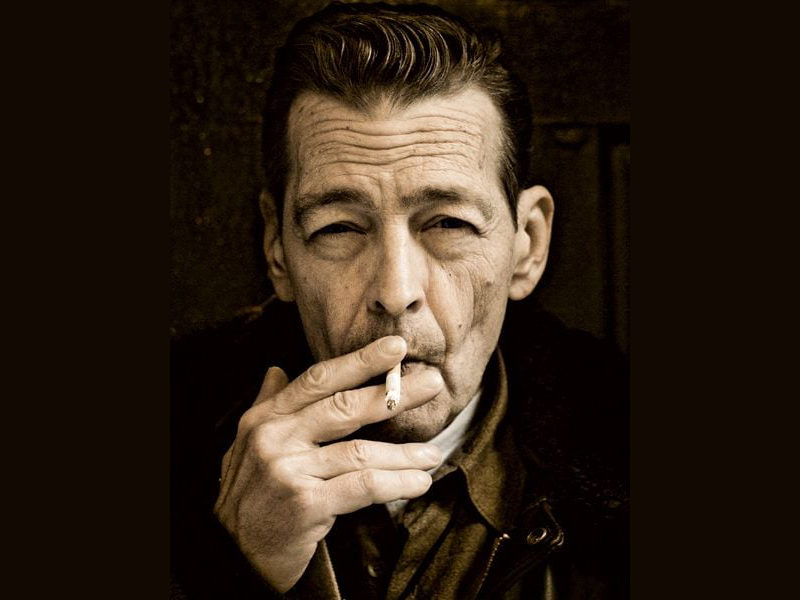

Last I saw him, he seemed fragile, a shadow of himself, but once he smiled, he was back. He was more than back. He seemed pleased to see me, and there was a kindness in his eyes I hadn’t noticed before. I was looking forward to watching him grow old and cranky.

I ran into him outside a small luggage shop on Bedford Street, near his favorite bookshop. He was wearing a trench coat the color of wet sand. The belt was hanging loose, and his hands were deep in the pockets. He nodded, as if we were already in the middle of a conversation.

“A lot of room in these pockets. You’d be surprised. I could pack a Beretta in here,” he said.

“Or a picture of one. In one of those little bedside frames you get at Woolworth’s,” I replied.

“Don’t forget. I’m from Newark.” He tilted his head and narrowed his eyes. “I know where to get …” He left the thought hanging. It hung for a little too long.

“Guns?” I suggested.

“Frames. Really nice frames.”

Brian Cullman is a writer and musician living in New York City.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/35OBTLL

Comments

Post a Comment