Jack Gilbert’s masterful “The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart” ends with lines that remind us of the very limits of language: “What we feel most has / no name but amber, archers, cinnamon, horses, and birds.” Hard Damage, Aria Aber’s debut poetry collection, pushes against those same limits, asking a great deal from the reader—emotional work as well as intellectual—but also allowing for understanding, comprehension, and, ultimately, meaning. Aber’s work here is often about the very notion of what language can do when faced with a shifting geography that requires us to describe both the self and the world: Berlin, Afghanistan, Wisconsin, the gods of Olympus, the guitarist John Frusciante, the German language, the mujahideen, and, during a particularly striking section, Rainer Maria Rilke. Aber is not afraid of erudition or the hard labor of crafting poems that peel open in layers; at times, reading her work reminded me of poets who have worked across similarly broad, deep linguistic topographies: Carolyn Forché, Frank Bidart, Paul Celan, Sylvia Plath, Wallace Stevens, and others. Aber’s work here is hardly derivative of those masters. She is her own poet, her own voice, and her debut is my favorite volume of poetry this year. —Christian Kiefer

I always feel terrifically small in SoHo—all those fashionable people and fancy stores and imperious cast-iron buildings. Last night I followed the long and lonely streets to the Drawing Center to see “The Pencil Is a Key: Drawings by Incarcerated Artists” and to focus, I hoped, on something larger than myself. The show highlights the drawings of incarcerated artists around the world and throughout history—from Gustave Courbet, imprisoned during the Paris Commune, to Valentino Dixon, who was released from Attica in 2018—with a particular emphasis on how these artists have “used the pencil to envision their freedom.” While this freedom takes many forms, I was particularly struck by pieces that imagined it architecturally: Herman Wallace’s drawings of his dream home, Henry Fukuhara’s rendering of a vast and colorful hydroelectric dam, and a hand-lettered and hand-illustrated manuscript titled “Yemen Milk & Honey Farms Limited Feasibility Report.” Drafted by Mansoor Adayfi, Abdualmalik Abud, Saeed, and Khalid Qasim—then detainees at Guantánamo—the manuscript envisions a sheep-farming business, including detailed diagrams for facilities that could house up to five thousand animals. Their vision is thorough and impressive. I could only hope to imagine, when subjected to such severe confinement, a built environment so expansive and full of purpose. —Noor Qasim

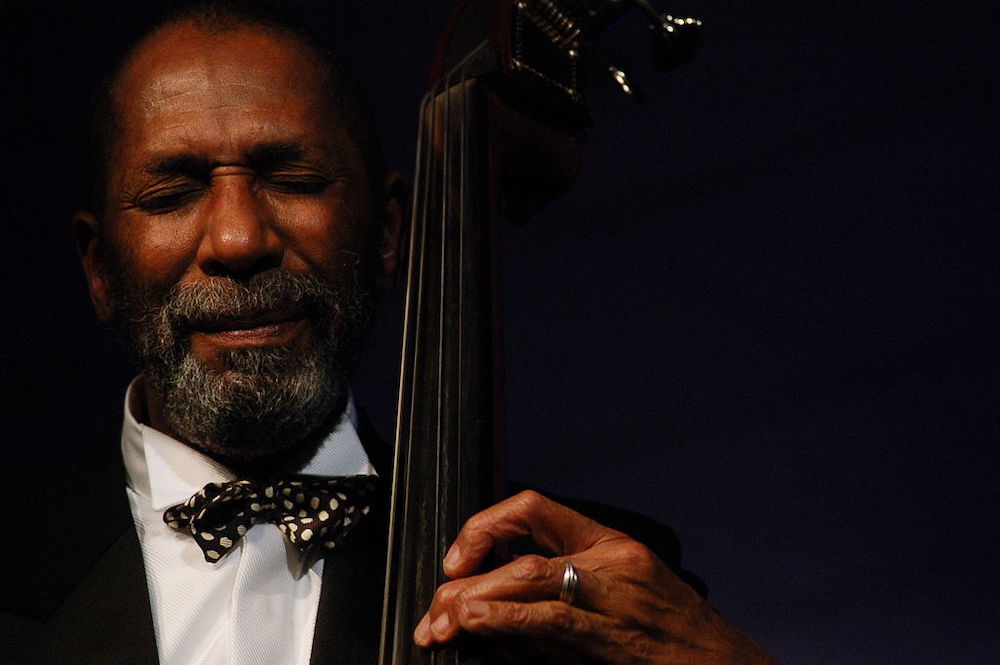

Ron Carter performing at the 2007 European Jazz Expo. Photo: Laura Manchinu (CC BY 2.0 (https://ift.tt/2HnEhxc). Via Wikimedia Commons.

This month, I did something I never do: go to Times Square twice in a week. My usual commute, social calendar, and low-grade agoraphobia have me spending more time on the edges of this island, but I braved the slow-walking crowds and the glaring billboards to make my way to Birdland. You see, October is Ron Carter month at the iconic jazz club, and Carter, a bassist with something like two thousand albums in his discography, which dates back to the early sixties and his time with the Miles Davis Quintet, is a living legend. My first visit, a Saturday night, was for the last of a string of performances by Carter’s big band. I’ll step into traffic for a good saxophone solo, and Carter’s group had great ensemble work along with standout soloists. In this configuration and others, Carter has an unparalleled ability to be both the star of the show and a generous collaborator, providing the backbone—and backbeat—for the ensemble. I went back a second time for the Golden Striker trio, with the pianist Daniel Vega and the incomparable guitarist Russell Malone: brilliant again. For ninety minutes, I forgot drums exist (sorry, drummer friends). Carter’s four-week residency continues this weekend with a quartet featuring the saxophonist Jimmy Greene; next week, he’ll round out the month with his nonet, which includes, inexplicably and excitingly, four damn cellos. Run, don’t walk. Or at least walk as quickly as the Times Square crowds will allow—Ron Carter is worth it. —Emily Nemens

Binaries snag at Saul Adler, the protagonist of Deborah Levy’s latest novel, The Man Who Saw Everything: East versus West, male versus female, bourgeois versus proletarian. Saul, a twenty-eight-year-old historian on his way to study male tyranny in 1988 East Berlin at the beginning of the novel, is a peculiar, slippery character himself, a male muse who chafes under the gaze of his photographer girlfriend; he falls in love with his translator, Walter, and inadvertently betrays him to the Stasi. These may sound like spoilers, but they’re not, not really; halfway through the novel, time folds in on itself, and 1988 East Berlin suddenly becomes 2016 London, post–Brexit vote. I’ve very much enjoyed many of Levy’s previous works, both fiction and nonfiction, but there’s something about The Man Who Saw Everything that captures the enormity of history, the frailty of time, and the question of Europe in a way that’s hard to describe. The word specter comes up frequently in the novel, as in the specter invoked by Marx and Engels and also Saul himself, but Levy shows us that for even those of us born after the Wall fell—and I am a member of that generation—the specter of history, of war, of borders and their ensuing binaries, still haunts us. —Rhian Sasseen

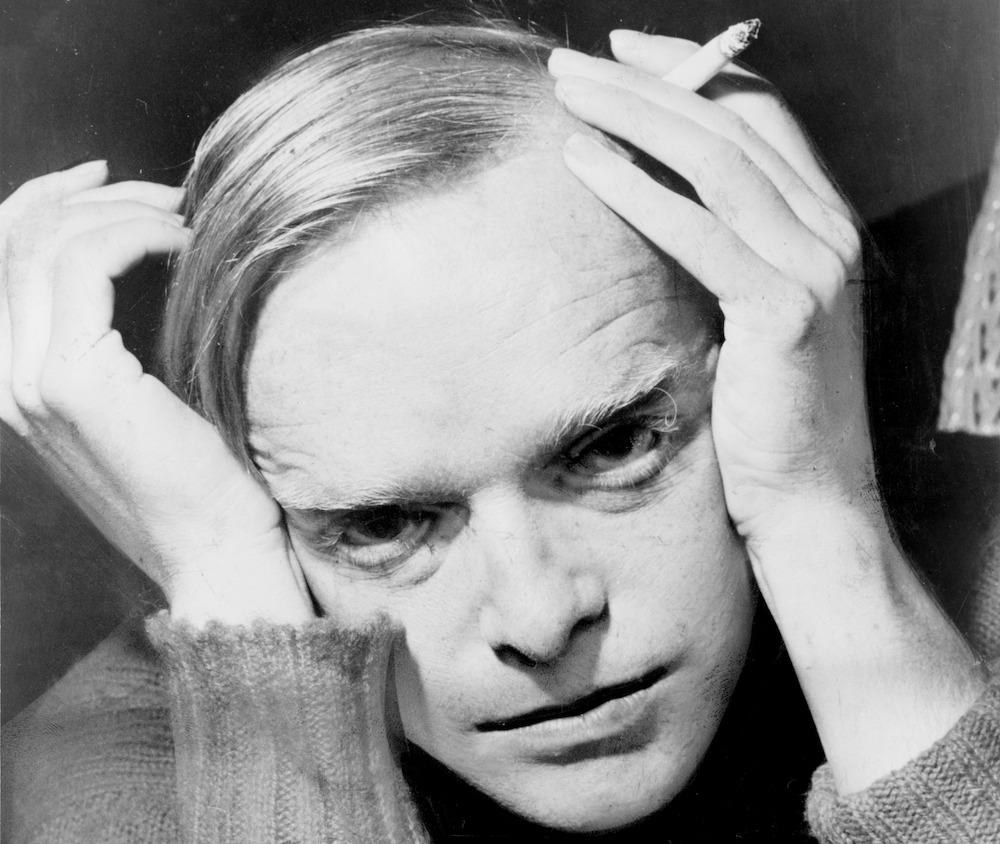

This past weekend I saw the U.S. premiere of Ebs Burnough’s documentary The Capote Tapes at the Hamptons International Film Festival. The film, which explores the life and lore of the late writer, is constructed around a series of reel-to-reel recordings made by George Plimpton in the nineties—interviews that were eventually compiled into the brilliantly subtitled oral history Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career. Those interviewed include Norman Mailer, Dick Cavett, André Leon Talley, and Capote’s close friend Dotson Rader, who offers a peerless impersonation of Capote’s toddlerish voice and states, with complete humorlessness, that Truman never believed anyone loved him. Particularly memorable for me is the footage of Capote wandering the desolate back roads of Kansas, hands clasped politely behind his back, while reporting In Cold Blood. There is something mesmerizing and lonely-looking about his small frame against that vast landscape. Much of the film confirmed dimensions of Capote’s identity I was already familiar with—Capote the literary legend, the eccentric, the raconteur—but these clips felt revealing of a different, more private side of his character: Capote the journalist, the addict, the self-isolating storyteller. While the film does discuss Capote’s celebrity and suicide, it’s not salacious. There are no big reveals. Rather, like a dinner party where a group of (very eloquent) people discuss an old friend, The Capote Tapes offers a collaborative portrait of the famed artist—one cobbled together from the voices of those who knew and loved him. —Cornelia Channing

Truman Capote. Photo: Roger Higgins for the New York World-Telegram and Sun. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/33FGZYX

Comments

Post a Comment