Novelist Lucy Ellmann’s perennial and revolutionary subtext is that women should enjoy pleasure.

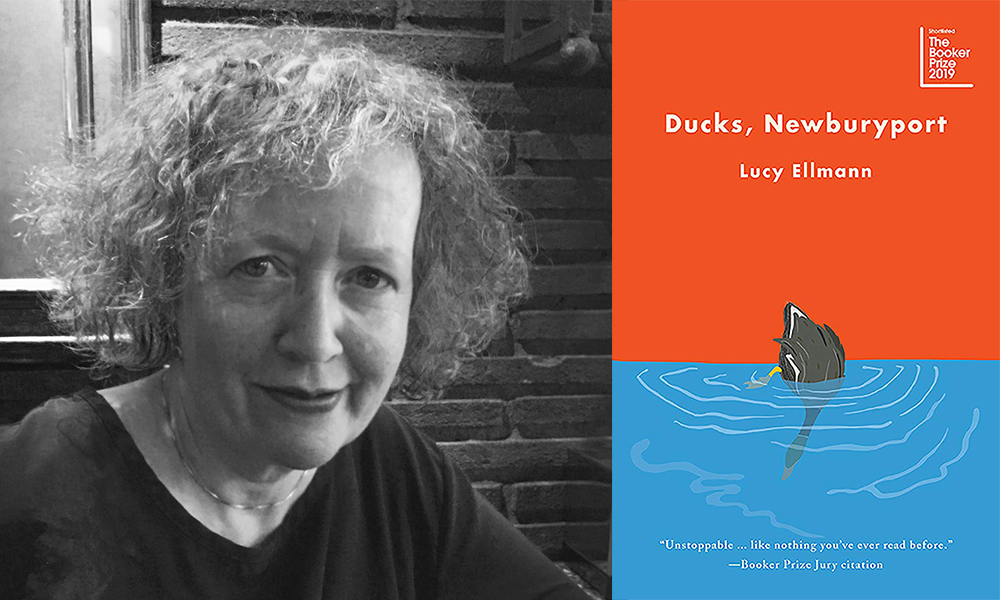

Lucy Ellmann’s great theme is the grim impossibility of proportion: emotional, moral, cosmic. Her Man or Mango (1998) begins with a disbelieving lament that the world kept turning after the Holocaust, instead of spinning faster to “fling us from the trees…hurl us into outer space.” And yet, who among us is capable of measuring personal preoccupations against the barometer of grand-scale tragedy? Ellmann’s latest novel, the Booker-shortlisted Ducks, Newburyport, is a sublime literary enactment of how guilt, grief, rage, regret, compassion, and every other emotion swirls and ebbs in unbalanced defiance of rational logic. Remembering a beloved parent’s drawn-out death clenches the heart of the unnamed narrator, but so does the plight of a two-year-old rhino rescued from the El Niño monsoons: “she must have been so frightened, poor little rhino, first the floods and then being manhandled.”

The very form of Ducks, Newburyport is, perhaps, the ultimate expression of life’s absurd disproportionality. The novel comprises a single, occasionally interrupted sentence, stretching over about a thousand pages, emanating from the fretful, intelligent, roving mind of a woman in Ohio, a professional baker and mother in her early forties. For Ellmann, such bold experimentation is nothing new. Her previous six books all eschewed the tried-and-tested approaches to novel-writing, sometimes to critical bemusement. Among other literary foibles, Ellmann is fond of lists, historical and scientific digressions, newspaper snippets, and—her most divisive habit—sentences that lapse into INDIGNANT ALL CAPS. Her 1988 debut, the semi-autobiographical Sweet Desserts, has an index, likely the funniest ever compiled: “Aloofness, see inhabitants of the British Isles, Aplomb, my total lack of social, 103…Penis, not the only mention of a, 37.” In Varying Degrees of Hopelessness (1991), a razor-sharp comedy of manners set in a superannuated London art school, some chapters contain only single sentence paragraphs. This captures, to unexpected and droll effect, the tense, covetous, fastidious personality of the main protagonist, thirty-something virgin Isabel. Here’s one of Isabel’s many crochety reflections:

It is amazing what people will settle for.

I saw a couple on a train once.

The woman looked much older than the man.

His name seemed to be Gavin.

Gavin had long hair in a ponytail.

Gavin had long hair and the responsibility of going for the sandwiches when they were traveling.

Truly pathetic: she, too old for him, crouching over her magazine, while he, merely too hairy, stalking off in search of British Rail sandwiches.

American critics have often credited Ellmann’s writerly eccentricities to the Illinois native’s longstanding residence in the UK, where she moved as a teenager. Reviewing Man or Mango in the New York Times Book Review, the novelist Lisa Zeidner mused that England “is currently far more hospitable to her brand of literary experimentation than the United States.” But Ellmann’s comedic brilliance is sui generis on any continent, as are her prickly, perceptive heroines, though they have much in common with each other. Disappointed by others but desperate for meaningful connection, Ellmann’s women are so uncompliant with conventional feminine decorum, so exhilaratingly pissed off at the world, that most other fictional characters seem like insipid, crowd-pleasing conformists by comparison. In Doctors and Nurses (2006), murderous healthcare worker Jen is a woman of “immodest” hatreds living in a “rural backwater” of England. The targets of her hatred range from the general—the nation, her species, everyone she’s ever met—to the specific: Nigella Lawson, Neighborhood Watch Schemes, synesthetes. “What do they MEAN green is the color of Wednesday? What the hell are they TALKING about and why do we let them get AWAY with it?”

What Jen “secretly loves” rather than hates is “her CUNT…She’s charmed by its quiet steadfastness, how level it stays as she walks.” Alas, Jen’s cunt “has been left to lie fallow for long periods,” despite her roiling libido. “In the ABSENCE of adulation, she wanks.” As an unabashed chronicler of female sexual frustration, Ellmann has no parallel, living or dead. Man or Mango’s Eloise, lovelorn and six years celibate, contemplates the dildo-esque potential of vegetables. “Her main worry: that some day a male nipple under a taut shirt would so entrance her she’d make a grab for it before she knew what she was doing.” Chastity-burdened Isabel wears Janet Reger knickers, obsessively reads romance novels, and seeks a deserving recipient for the “precious gift” of her virginity. Even the narrator of Ducks, Newburyport, who is happily married to an academic named Leo, often wishes she had more sex. But many obstacles stand in the way, not least “the fact that when I do have any excess energy, I like to spend it being regretful and embarrassed.”

Ellmann’s perennial and revolutionary subtext is that women should enjoy pleasure. “Food is an immediate source of satisfaction,” she told the Irish Times in 1998, bemoaning the cult of skinniness. “And sex would be, but it’s harder to arrange.” Her 2013 novel, Mimi, is an ode to sensuous joy in which a cosmetic surgeon falls in love, to his surprise, with a plump menopausal epicurean and quits his job. “What women need is less scrutiny of how they look,” Mimi schools him, “not more nose jobs.” Mimi’s amatriciana recipe, included alongside ones for her eggnog and “Mom’s jam,” instructs: “Kiss me. Chop two-inch hunk of guanciale (smoked) into large half-inch-thick pieces. Kiss me again.” The narrator of Ducks, Newburyport, who makes and sells tartes tatin, sour cherry pies, cinnamon rolls, and lemon drizzle cake, is deprived, ironically, of the bliss her baking gives others. “I’m always thinking about recipes and all, but I forget to eat, the fact that it’s hard to cook if you’re full, so I just got out of the habit.” It’s a resonant metaphor for the condition of motherhood, and womanhood in general.

In a broader sense, Ducks, Newburyport’s epic portrait of one woman’s limitless polyphonic thoughts is an apt representation of emotional labor. While ruminating over spree shootings, the reign of Trump, Kondo-ing, industrial pollution, beauty YouTubers, the fiasco of American healthcare, and quite literally everything else of significance in our contemporary culture, she is worrying about and taking care of her four children, making and delivering baked goods, calculating financial outgoings, anticipating future tasks and demands, and itemizing her regrets, failings, and sorrows.

…a chick for Jake, that fact that where is Jake, hake, cake, bake, wake, make, fake, take, lake, lake effect snow, the Great Lakes, the great unwashed, why am I, the fact that, for Pete’s sake, everybody, why are there so many wet towels on the bathroom floor, Stacy, Stacy at five, the fact that an abused dog named Pumpkin now has a home, lost button, the fact that I really gotta do the grouting, The Staggering Cost of Alzheimer Care, the fact that where could that button be from…

The free-associative stream accumulates into a work of great formal beauty, whose distinctive linguistic rhythms and patterns envelop the reader like music or poetry. Equally, it forms a damning indictment on capitalist patriarchy that, in an extraordinary feat from a writer at the height of her powers, never veers within a mile of sanctimony or self-righteousness. If art is measured by how skillfully it holds a mirror up to society, then Ellmann has surely written the most important novel of this era. And with an off-the-cuff remark, she also happens to have given us the slogan of the era. At a finalists ceremony for the Man Booker at the Southbank Centre in London, Ellmann was asked to elaborate on an earlier assertion that the length of Ducks, Newburyport has only been criticized because she’s female. She replied, “Essentially, I think it’s time for men to shut up completely.”

Emma Garman has written about books and culture for Lapham’s Quarterly Roundtable, Longreads, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Salon, The Awl, Words without Borders, and other publications. Read her Feminize Your Canon column for The Paris Review Daily here.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2JeONcj

Comments

Post a Comment