John Vincler’s column Brush Strokes examines what is it that we can find in paintings in our increasingly digital world.

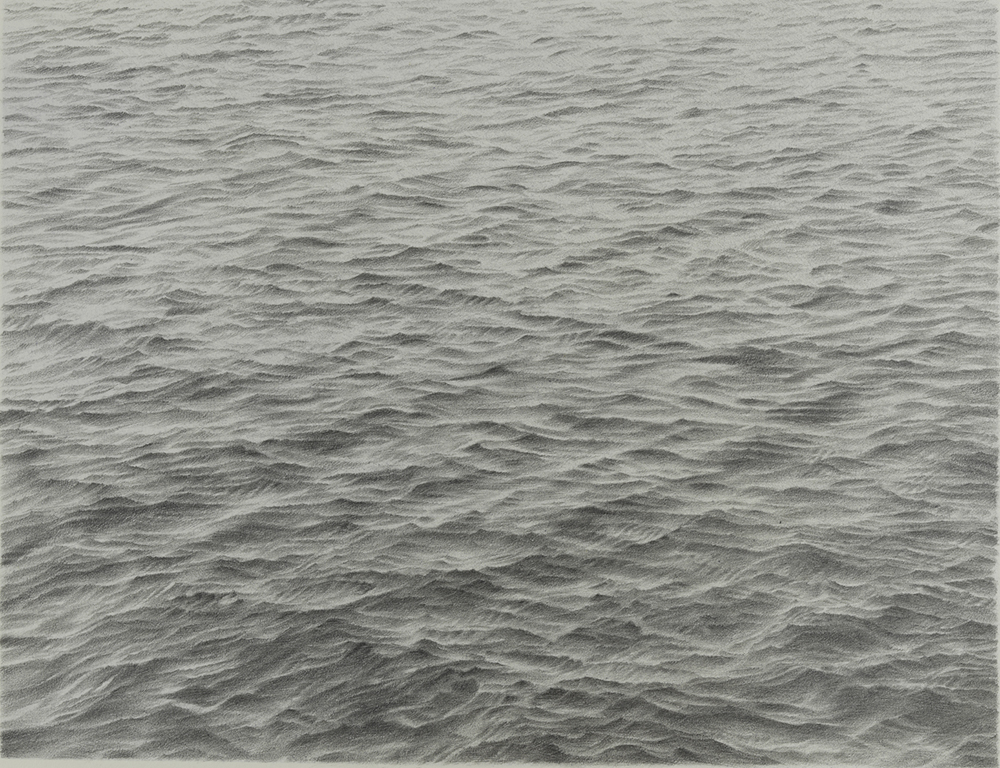

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Ocean), 1973. Collection of Aaron I. Fleischman © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

Open sea water seen from above. Star-filled skies. Stones. Gray after gray: from the graphite of pencils, charcoal on paper and its erasure, oil paint in layer after layer of deep, smooth near-black. Forays into ochre and midnight blues, the earthen tones of sand and stone, then returning seemingly always to gray. Before seeing the objects, works on paper, and paintings gathered together at the Met Breuer for the immense Vija Celmins’s retrospective, “To Fix the Image in Memory,” I had previously witnessed the gnostic perfection of the later paintings of ocean waves and night skies. The Breuer exhibition was the first time I was able to trace in person the artist’s development from the early paintings of objects and appliances in her studio (a hot plate, a fan, a lamp) to her distinctive late work. What I didn’t anticipate from this exhibition was the suggestion of utter desolation.

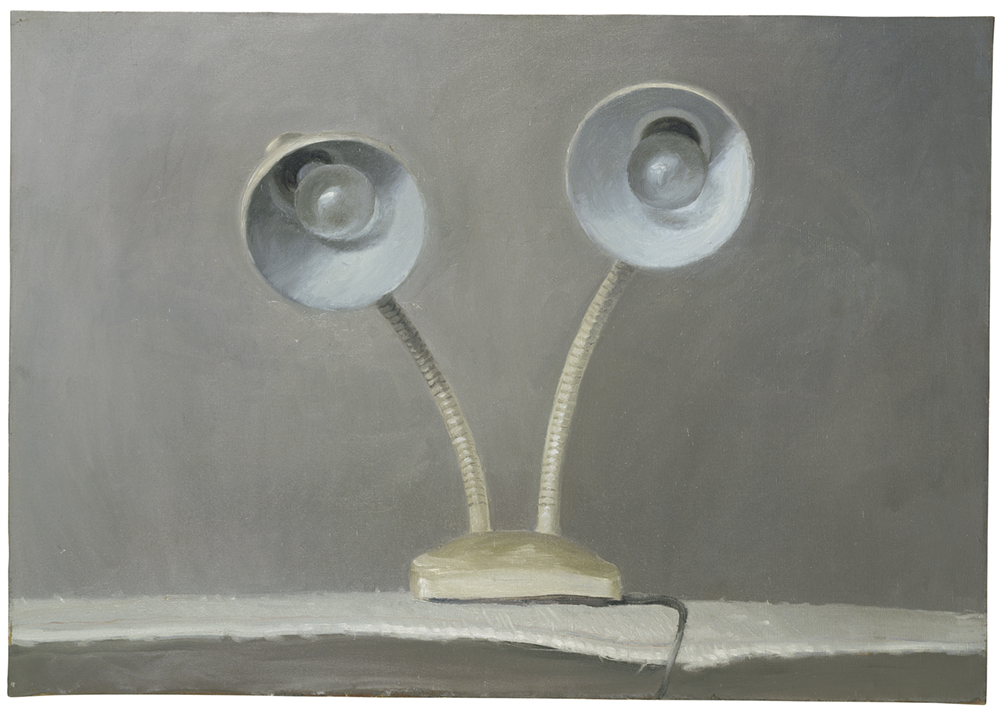

I should say that Vija Celmins paintings are not about this sense of foreboding. The artist has said, “I am not interested in telling stories.” And yet art exhibitions, career retrospectives in particular, do engage in storytelling. What is an exhibition but an essay written with objects in three dimensional space? Celmins’s biography and the sequence and development of her work proceed in an ordered and coherent fashion across two floors of the Breuer. Vija Celmins was born in Riga, Latvia, in 1938, two years before the Soviet occupation. A decade after her birth, her family moved to the United States where they settled in Indiana. Clemens drew animals in her notebook in the back of the classroom while the teacher spoke in a still-unfamiliar foreign language, English. After earning her B.F.A. in Indiana, she headed to California as an art student in the M.F.A. program at University of California, Los Angeles, where she would find a studio near the beach outside of downtown Venice. Here the studio interior itself became her object of study, particularly the functional objects within it. The resulting paintings read more like portraits of inanimate objects than still lives. A lamp stares back at the viewer with its two bulbs, the orange coils of the heater and hot plate in two separate paintings glow with an almost palpable animal heat from their gray perches on the floor and a shelf respectively.

Vija Celmins, (American, b. 1938, Riga, Latvia) Lamp #1, 1964. Collection of the artist, courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Photo: Sarah Wells

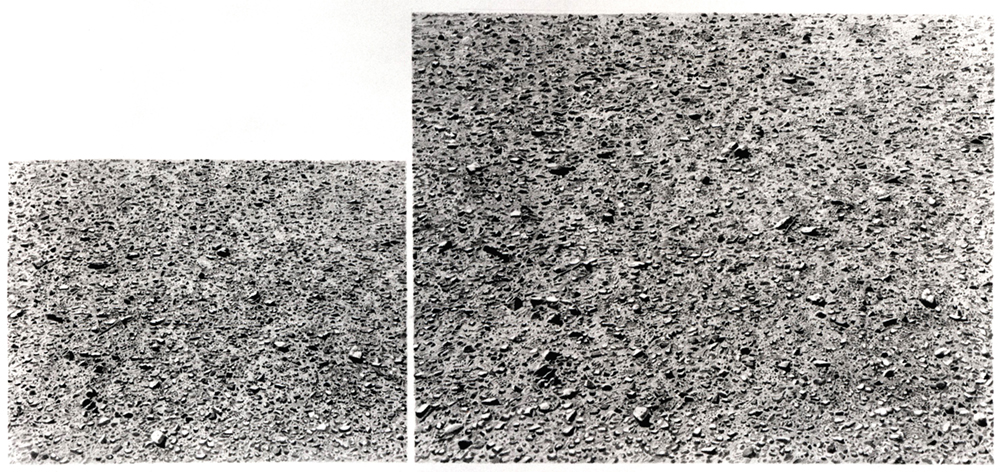

Celmins was an LA artist before that was fashionable and once it was fashionable her work never read as very LA (again, all that gray). She is either detached from the New York art world, or in dialogue with it from what seems like a vast distance away, with the message changed beyond recognition along the way. In the sixties, she moved away from painting into making sculptures of oversize objects—a hyper-realistic pencil, scaled to the length of a person; oversize erasers—which relate conceptually to pop art but are of a strikingly different character. Celmins’s sculptures remain inward-looking, a new avenue for obsessively documenting the tools and objects found in the studio and used by the artist. They also foreshadow a move, gradual at first, toward meticulous drawings made with pencil on paper prepared with an acrylic ground. For a time, magazine clippings provided her subjects: warplanes, an explosion at sea, a floating zeppelin, and, in 1968, her first moonscape. An early drawing of the open sea, sourced from her own photograph, was also completed in 1968. (There are striking affinities between Celmins and Gerhard Richter’s work from this period, although they were not aware of one another.) By the seventies, she had all but abandoned painting for works made with pencil (without the use of an eraser). The narrative, as it is spun, both in the exhibition itself and in the many reviews, leads us to the arrival of Celmins’s almost transcendental subjects: mostly the open seas and starry skies, but also spider webs, desert floors, clouds, and, again, the surface of the moon. Instead of objects, in this late work she paints or draws expanses.

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Double Desert), 1974. Collection of Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery

Vija Celmins paintings and drawings feel at once mystical and philosophical. Through all of their insistent gray, they hum with an inherent melancholy, that somehow doesn’t deaden their sense of life and activity. Her works are wondrous and vibrant while also paradoxically stilled (the undulating surface of the sea stopped in a moment) and delimited (the expanse of space contained in a small rectangle)—alive, yet rarely enlivened by anything as distracting as color. Mystical because they often conjure the unknown. Her great subject might be the abyss, depicted through the known and recognizable: the sea, outer space. Philosophical because Celmins returns to first principles. A return to painting as representation, or more than this, art that reassembles truth. The title of the exhibition, “To Fix the Image in Memory,” takes its name from a sort of artistic-philosophical game she played, a game that brought her back to painting by the end of the seventies, before her move to New York in the eighties. Celmins collected stones from the beach or desert, took them home, and then made bronze casts of them. Each individual cast was then painted as a twin facsimile of an original, both were then set before a viewer to see if any difference could be discerned between, in her words, one “found” and one “invented.” Celmins’s work is not simply about obtaining a likeness. It is about seeing and process and working the materials so as to render something that is not only an object of artistic labor, but the result of great and, ultimately, mysterious contemplation.

Vija Celmins, To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI, 1977–82. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Edward R. Broida in honor of David and Renee McKee © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

In an interview, she describes her process of composing the star-field paintings. Of painting and then sanding the surface smooth again and then repainting, repeating this process as many as a dozen times. Is this layered yet anonymous quality (there are no discernible brush strokes), what gives the images their depth and presence? In an almost offhand comment she describes these as “a lame attempt to make something that can remain … like the end of art history, and this my answer to it.” “Lame” perhaps because she recognizes that the work is doomed, as every made thing is doomed. Whatever their fate, while they remain, these works should be treasured, shown, seen, and contemplated.

*

We of course bring our own stories to the art we see. In the weeks before seeing the Celmins show at the Met Breuer it seemed every conversation I had included quips about climate change, the discomfort bubbling to the surface for everyone. “If there is a future, when we’re old,” someone I met for the first time said, as I was holding my child. “Sailing will be a useful skill, after farming, in the decades ahead,” said a friend about to head to Iceland to write about climate change, uncertain if she’d return to New York. I read that the Upper Peninsula in Michigan, where I just spent a few weeks, may be one of the best-suited geographic sites for surviving a climate crisis in the contiguous United States. This relates to the futurity I sensed in Celmins’s work, which I failed to see when I saw her recent paintings at Matthew Marks Gallery in 2017. It occurred to me that Vija Celmins could be described as a painter of geological time. That much of her later subject matter consists of what will remain when and if human beings are no longer: the sea, the solar system, rock and sand, stones and sky. Will clouds remain? Spider webs? These are the questions her work has left me asking as I encounter it in 2019.

Vija Celmins, Falling Star, 2016. Private collection © Vija Celmins, courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery Photo: Ron Amstutz courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Celmins’s paintings and drawings made me think anew about of one of my favorite novels, David Markson’s Wittgenstein’s Mistress. The central and sole character, Kate, appears to be the last living person on earth after some unnamed cataclysmic event. She occupies a house on the beach, or rather a series of them, when she is not spending her winters living in the world’s great museums (the Metropolitan Museum and the Louvre, among others), where “she burned artifacts and certain other objects” for warmth. Once, after leaving her cooking to urinate on the beach, she turned back to see that the house was burning. So, after watching her house become consumed by fire, she simply moved on to another. But she would still see the other house sometimes on her walks down the beach. “One is still prone to think of a house as a house, however, even if there is not remarkably much left of it.” After leaving Celmins’s exhibition, I thought to myself that in one of those otherwise emptied out museums, Celmins’s work would seem almost singularly prescient. Yes, like an answer to the end of art history. Painting for the Anthropocene. Nature painting wholly divorced from romance. But maybe this is too much. I look at the news. Multiple wild fires are burning across California with names like Kincadefire, Tickfire, Skyfire, and Gettyfire. Hundreds of thousands evacuated from their homes. Nearly a million people without power. Prisoners conscripted as firefighters. The Getty Museum campus, with its store of invaluable art objects, is in its namesake fire’s path, protected only by fire retardant dropped from airplanes and its own fire-resistant design. What might we discern of our future in Vija Celmins’s ashen yet beatific grays? What will remain after everything burns?

To Fix The Image in Memory will be on view at the Met Breuer in New York City until January 12.

Read earlier installments of Brush Strokes here

John Vincler is a writer, visual artist, and has worked for a decade as a rare book librarian. He is editor for visual culture at Music & Literature and is at work on a book-length project on cloth as subject and medium in art.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2Ok85jo

Comments

Post a Comment