Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re thinking about travel—by train, plane, car, or bus. Read on for Jack Kerouac’s Art of Fiction interview, W. S. Merwin’s essay “Flight Home,” and Paulé Bártón’s poem “The Sleep Bus.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door.

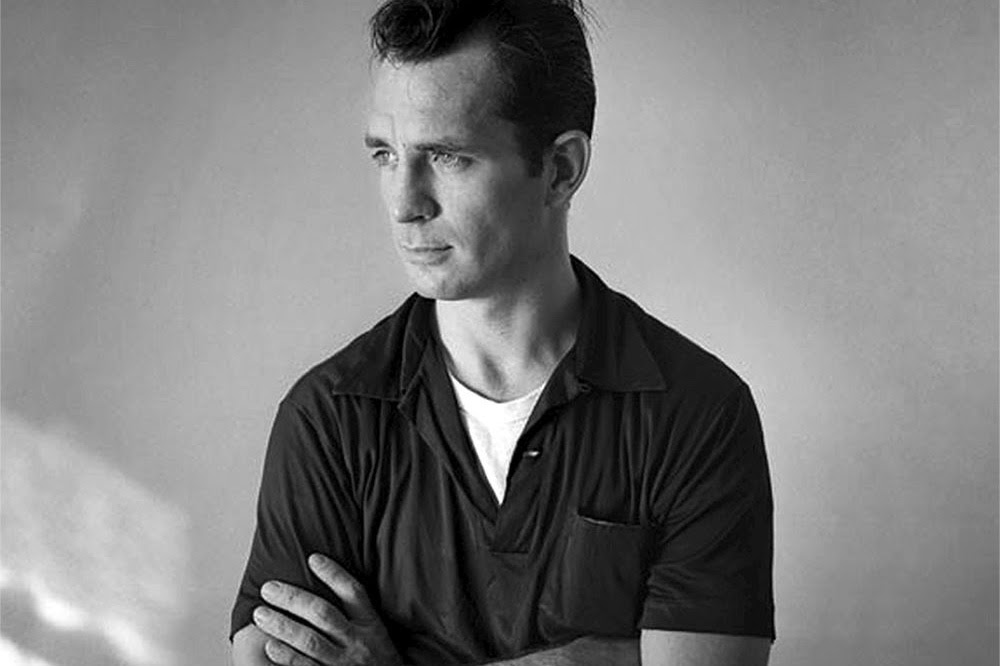

Jack Kerouac, The Art of Fiction No. 41

Issue no. 43 (Summer 1968)

I spent my entire youth writing slowly with revisions and endless rehashing speculation and deleting and got so I was writing one sentence a day and the sentence had no FEELING. Goddamn it, FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings.

Flight Home

By W. S. Merwin

Issue no. 17 (Autumn–Winter 1957)

They say that after seven years every cell in your body has changed. You are a different person.

I wish I could remember what day it was, in July 1949, that I landed in Genoa. Or the day (one or two days before?) when we first came in sight of the Spanish coast.

Strange, now I am going back, to think that I have been in Europe without a break, ever since I was a minor. Ever since I was twenty-one.

The Sleep Bus

By Paulé Bártón

Issue no. 70 (Summer 1977)

I get on

the racket bus,

and see one empty seat

next to a burlap-face

mongoose

in a cage …

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/34oyJ0i

Comments

Post a Comment