In his column “Line Readings,” Ivan Brunetti begins with a close read of a single comics unit—a panel, a page, or a spread—and expands outward to encompass the history of comics, and the world as a whole.

Comics are often likened to short stories and novels, or (more improbably) animated films, but in a sense they are also a kind of poetry, an incantation beckoning us to enter their world. The simplicity of their superficial concision can reveal surprising density, layers, and multivalence. In a poem, lines might form and fill a stanza, which literally means “room”; and so it is with comics, where panels could likewise be thought of as stanzas. Rows, columns, and/or stair-steps of panels, in turn, structure a page (or an entire story) of comics and give it its particular cadence. Even the simplest grid tattoos its rhythmic structure onto the page.

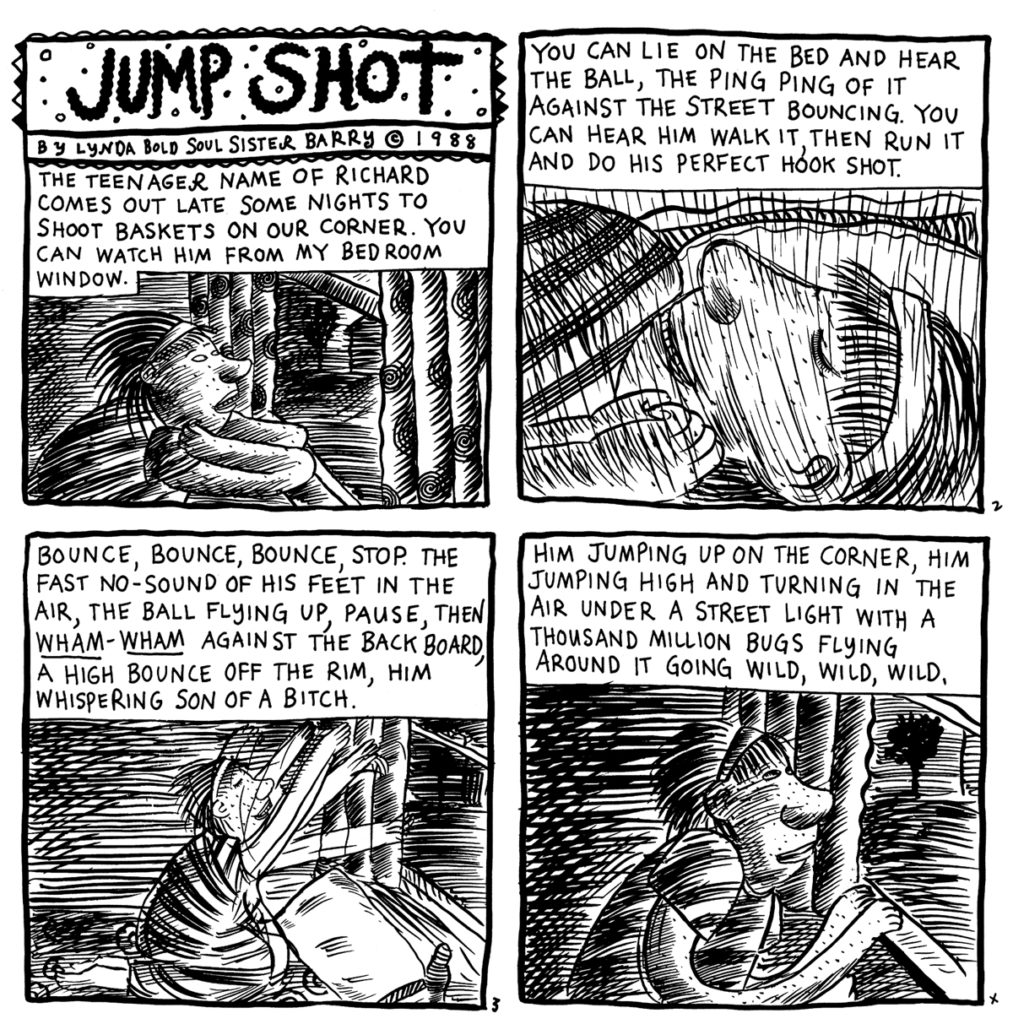

The one-page story “Jump Shot” by Lynda Barry (1988), an installment of her comic strip series Ernie Pook’s Comeek, comprises, to put it into the simplest, crudest terms, a large square box subdivided into four smaller square boxes. Inside each box is a view into one room, containing just one character, a young girl, in successive moments. This is as elemental as comics get: one character in one space, in one continuous action, spanning just a few panels, all housed within an evenly sectioned grid. However, even an element contains vast inner spaces and subatomic particles elusively whizzing and whirring within it, and this seemingly simple strip is, in fact, quite complex and nuanced. While the name of the young girl is not mentioned here, we nonetheless are invited to see what she sees, imagine what she imagines, and feel what she feels. And amazingly, we do.

How is this accomplished in just four panels? Before we begin reading the strip, we visually absorb the entire story as a whole, and there isn’t much in the way of action: two somewhat static panels, one close-up, and only one panel showing movement. At first glance, it all appears very… small. But is it?

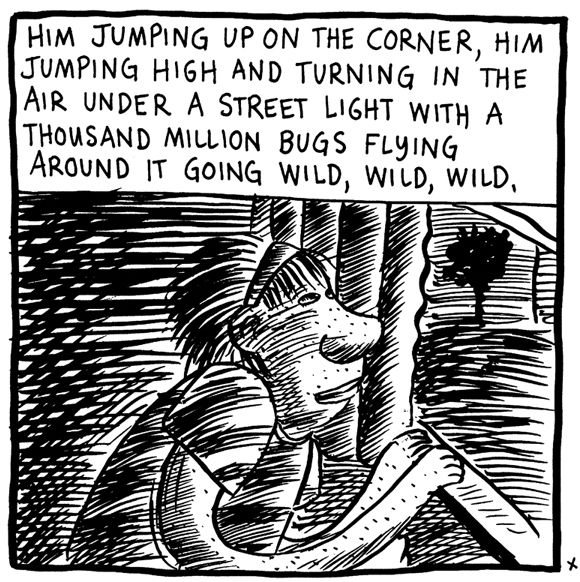

Panel 1: We see a girl looking out a window, indicated with the gestural drawing of curtains, sash, and sill; we also see a hint of a tree and a house in the distance, and the dense hatches suggest that it is night. From the girl’s pose, we can discern that she is rapt with attention, and we readers are likewise tantalized: we, too, want to see what is outside that window. The girl faces to the right, mirroring the direction in which we are reading the strip, and so our eyes effortlessly follow her eyes. We connect the caption box with the character (it hovers above her head, like a thought) and as we read it, we understand that the narrator is the young girl. We are whooshed into the scene.

Breaking it down: “The teenager name of Richard” is in kid-speak, implying that the narrator is a kid younger than a teenager. We know exactly the who, what, when, and where: the girl is in her bedroom, observing Richard, late at night, shooting baskets alone on the corner, specifically, “our” corner. This is how kids would refer to their own block, but the “our” also suggests—gently, conspiratorially—that we readers are also kids living on this same block. The use of the second person (“you can watch”) is a further invitation to the reader to be a direct participant in the story, not a mere spectator. Note that we “can” watch him, another invitation; we are not actually forced to watch, as he does not exist as a drawing in the story. The words and the girl’s body language are what allow us to imagine that we, with her, are watching Richard. This first panel jam-packs an impressive amount of narrative detail: the setting, characters, and point of view are established with economy, authenticity, subtlety, originality, and grace.

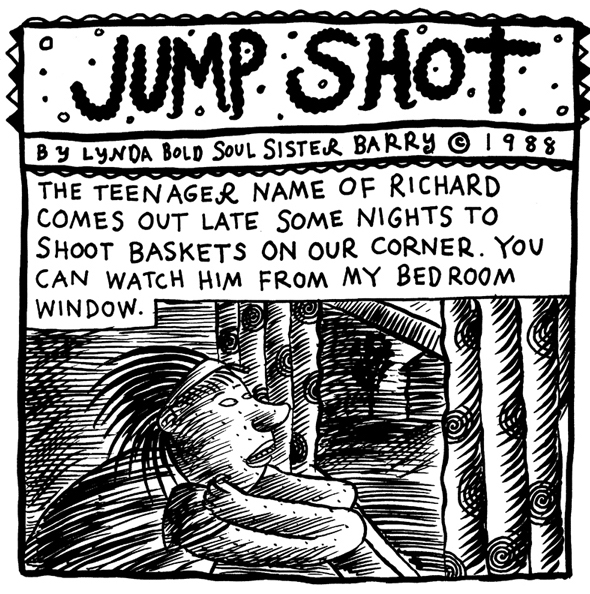

Panel 2: Having clearly established the scene, the artist is able to shift and vary the visuals in this panel, which differs from the others in several respects: it offers a close-up view of the character lying down, she faces up and not left, and her eyes are closed; she and we are going inward. Moreover, this is the lightest panel, the other panels getting darker and darker as the night progresses, indicated with ever-heavier hatching in the final two panels. The thinnest lines appear here in panel 2, cascading in a soft, enveloping glissando of hatches, the overall effect being that this is the most “internal” of the four panels, the girl lost in revelry. The language becomes more poetic as well, with onomatopoeia (“ping ping”) and the synaesthetic blending of movement and sound (we “hear” the walking, running, and throwing). A stunning choice by the artist: the girl, and we readers, never see this “perfect hook shot” but are left to imagine it. The words do not illustrate the picture; rather, they create empathy by merging our mind’s eye with the girl’s.

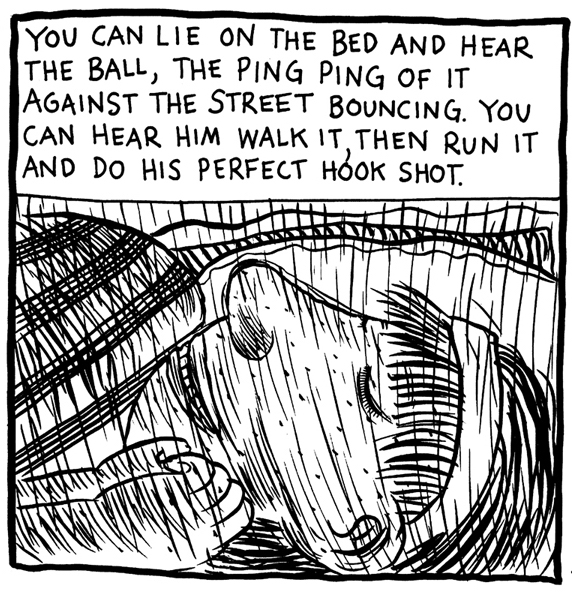

Panel 3: Now our eye has to shift diagonally down and to the left. Some sleight-of-hand occurs during that brief transition: the word “you” disappears from the narration. The dividing wall between reader and narrative has disappeared. We have been transported and are “there,” fully present, experiencing this specific moment, with this character, in this room. The rush of expressive verbs in the caption is ideally suited to this, the most active panel. The girl’s arms flail wildly, imitatively trying to keep pace with the quickly moving Richard. Again, we do not need to see Richard, because both the energetic hatches and playful words sketch him in for us: for example, the sequence/block of words “bounce, bounce, bounce, stop” even resembles, e.e. cummings-style, the very action it describes. Indeed, this caption is a torrent of pure poetry, rendered in the rich, unpredictable language of children: “the fast no-sound,” the insertion of the word “pause,” the underlined “wham-wham,” the funny whispered swear at the end.

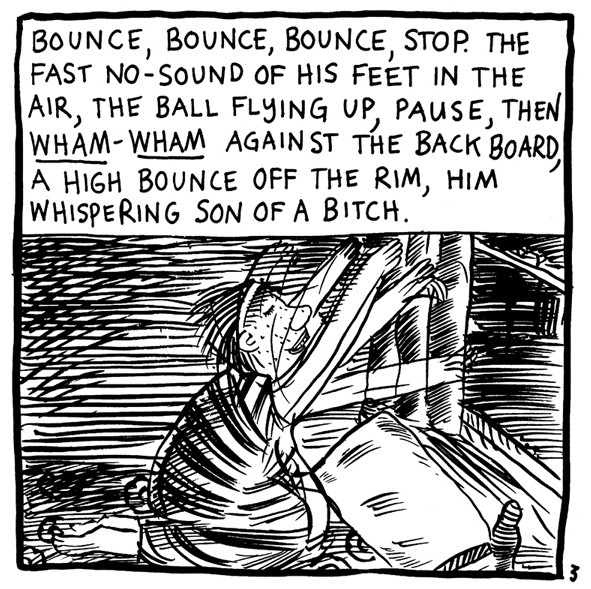

Panel 4: This final panel in some ways recalls the first: a mid-shot of the character looking out the window, this time with hands instead of arms perched on the sill, but the reader is slightly closer to her. The unusual objective-case–gerundive construction (I don’t pretend to be a grammarian) continues: “him whispering” from the previous panel is followed by “him jumping” and then builds to “him jumping high and turning.” We conclude with some charmingly hyperbolic math (“a thousand million bugs”) and the ecstatic repetition of “wild, wild, wild.” This panel feels silent, otherworldly: Richard has transformed into a being of swirling energy, at one with nature.

In this self-contained short comic, the girl is under Richard’s spell, and we are under Lynda Barry’s spell. We need not have lived this exact moment, we have likely had similar moments of immersive intensity burned into our memory. The artist conjures, with humor and without fuss, a heightened awareness, an internal response to the external world, and a shared experience. Moreover, the drawing hand is always visible, in its movement, so the linework is never neutral, not even in the panel borders, reinforcing a sense of intimacy and vulnerability.

The byline is listed as 1988, but the action could be taking place in 1968 or 1998, yesterday or tomorrow, or at the very moment of reading. Drawings are time-consuming to produce and thus inevitably show us a form of “then,” but through the ineffable magic of cartooning (or, more effably put, through drawings arranged in a deliberate sequence), the audience is lured in and transported to a “now.” The specificity of language, mood, and sensation leads us to assume that this comic might be a re-created memory, or at least partially rooted in a memory, an adult convincingly tapping into their childhood while simultaneously allowing us to tap into ours. Part of Barry’s genius is that she found the porous center wall between autobiography and fiction (what she has humorously but accurately termed “autobiofictionagraphy”). One might roughly imagine a Venn diagram with “literature” as the overlap between two larger twin circles, i.e., autobiography and fiction. Now imagine two eggs, over easy, and a fork joyfully breaking them up, letting the yolks run where they may, until we have a gooey, delicious mess: Barry’s process is the swipe of toast that soaks it all up.

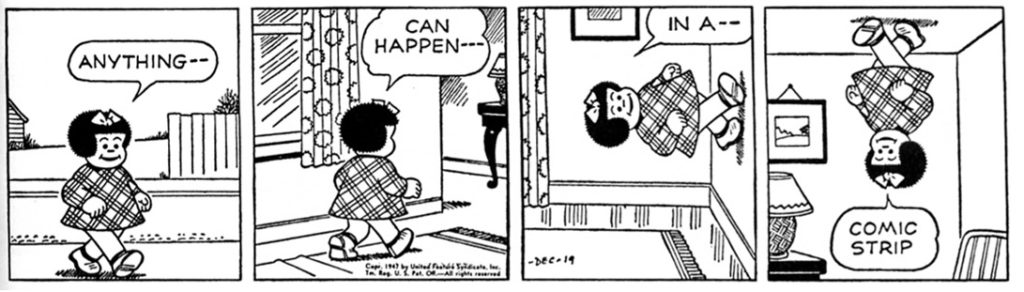

The four-panel strip is the classic format of daily funnies, employed countless times to the point of generic-ness: ubiquitous, invisible. Setup, development, repetition, then punch-line. Bounce, bounce, bounce, stop. All the better if the stop is somewhere unexpected. Someone like Ernie Bushmiller (artist of Nancy), the quintessential comics technician, precisionist supreme, could wring something surreal from this basic formula by revealing the strangeness latent within mundanity. We are grounded by rigidity, repetition, and predictability, and then we are just as quickly disarmed. Charles Schulz eventually modified this formula with his strip Peanuts, forging a more complex variation: set-up, development, punch-line, and in the final panel, a lingering existential continuation, essentially serving as a second (if sometimes melancholy) punch line. The strip from September 1, 1960 exemplifies how much story, characterization, and emotion can be uncoiled from the cartoon shorthand of doodle, balloon, and squiggle.

Ernie Pook’s Comeek was drawn by Barry from 1979-2008, and at its peak appeared in 70 alternative (typically weekly) newspapers nationwide. Along the way, the strip has been collected into books (The Greatest of Marlys is an essential volume, reissued in 2016 by Drawn & Quarterly, who is now publishing Barry’s ouvre, including her newest work). It’s impossible to list here Barry’s multitude of projects, which span memoir, graphic novel, regular ol’ novel, playwriting, radio, public speaking, creative workshops, teaching, and several innovative drawn-written-collaged pedagogical guides. She was deservedly awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2019.

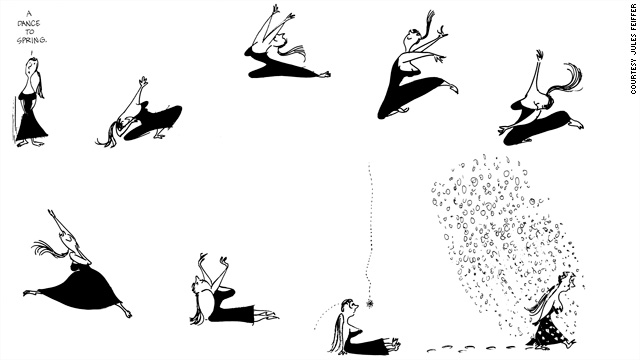

In the early part of the previous century, comic strips were one of the main selling points of newspapers. At mid-century, weekly/alternative papers allowed cartoonists to address adult concerns more directly and frankly. In 1956, Jules Feiffer began his hugely influential satirical strip (Feiffer) for the Village Voice, the first book collection of which, Sick Sick Sick has a wonderfully rhythmic title. Feiffer dispensed with drawing panel borders, simply implying the grid’s presence; no small feat, as the phantom grid structure is always clear. Lynda Barry’s work often appeared alongside that of her friend and contemporary, Matt Groening, who might use one panel, nine, or 50, alternating between minimalism and maximalism. The constraints of working within a finite space (paper also being a finite resource) could be liberating: cartoonists such as Mark Alan Stamaty condensed and concentrated content while experimenting riotously with structure.

Alas, many newspapers, including weekly papers, have disappeared, and others have largely (and pragmatically) migrated online. Comics may once have been rabbit holes located on finite, tactile newsprint pages, but today we spend most of our time peering through black holes anyway: infinitely deep, interlinked screens. Will print-based static compositions eventually become a quaint thing of the past? Will a new form emerge in their wake?

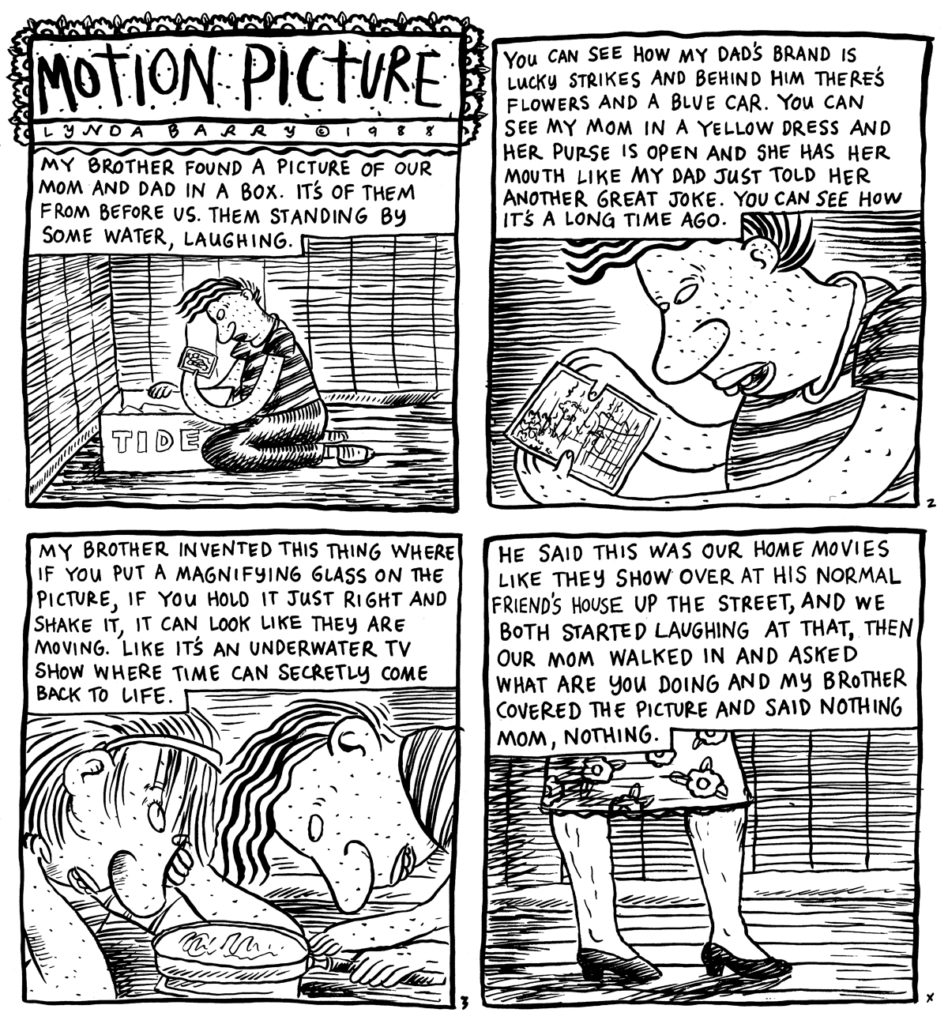

Barry has often cited Bil Keane’s comic strip The Family Circus as a refuge, beacon, and inspiration. As a child, she could escape into its small, circular, ink-on-paper world, where there existed a more functional, stable existence, a welcoming place to belong and perhaps feel a little less weird, less judged. Barry’s bestows upon all of us, readers and artists alike, a similar gift. This is from her most recent book, Making Comics: “Stories that lend themselves to comics can be found in a certain kind of remembering I sometimes call an image. It’s a sort of living snapshot, the kind of memory you can turn around in.” I am reminded of her strip “Motion Picture” (also from 1988, also worthy of an article), wherein a magnifying glass lightly shaken over an old photo creates an undulating picture, and “time can secretly come back to life.”

Ivan Brunetti is a professor at Columbia College Chicago, the author of Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice and Comics: Easy as ABC, and the editor of both volumes of An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories. His drawings occasionally appear in the New Yorker, among other publications.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/38Jf398

Comments

Post a Comment