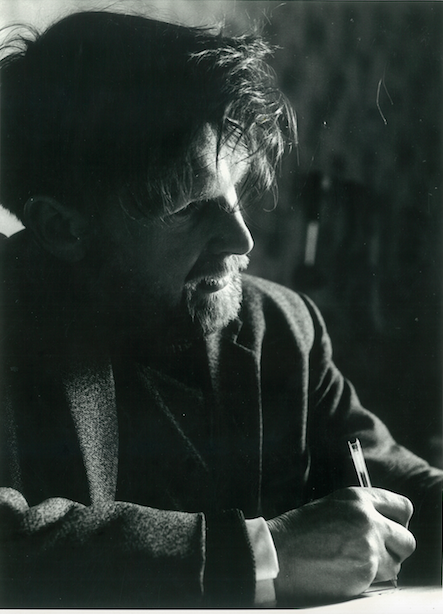

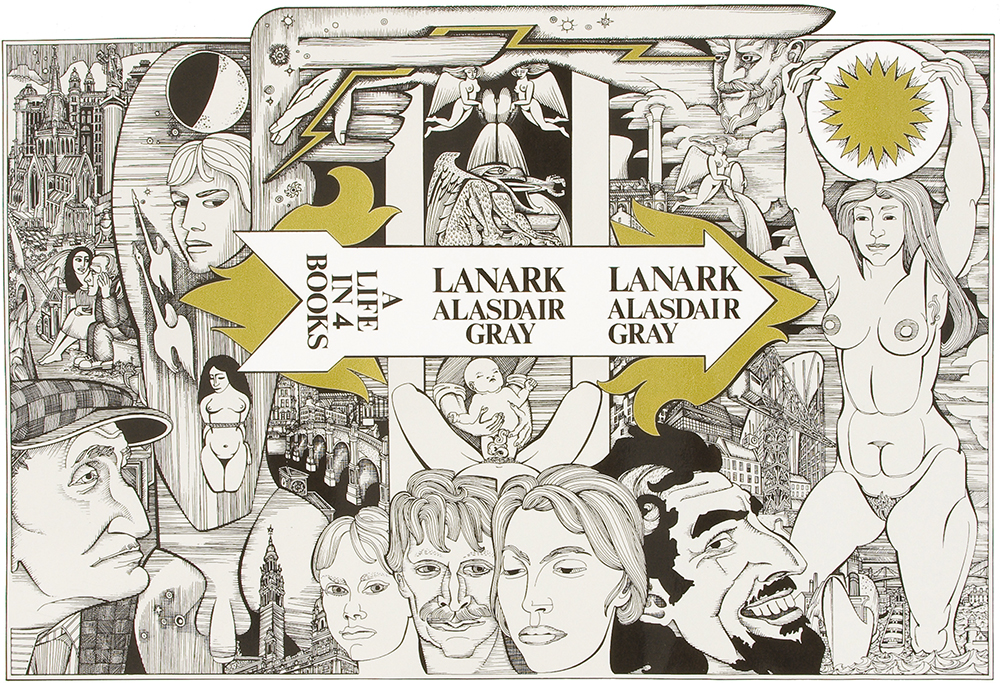

The Scottish writer Alasdair Gray died on December 29th, at the age of eighty-five, four years after a fall from the outside steps of his house left him with a spinal injury that confined him to a wheelchair, and almost three years after I went to Glasgow to conduct an Art of Fiction interview with him for The Paris Review. Gray was a Whitbread Award–winning author, best known for the weird speculative work, Lanark, an autobiographical tale in four out-of-order books (two of them non-realist), and several volumes of short stories, but also for his painting, for illustrating his own work, and for cutting a wide and eccentric swath in the Glasgow arts scene. He was a socialist, an advocate for Scottish independence, a fierce proponent of friends’ work, and a tireless critic of the craven or pompous. Re-reading my interview with him now, on the occasion of his death, I’m amazed by how cool and professional it is, and how much it leaves out, as I suppose it had to, of what Gray was really like, and what he meant to me.

I’ve written before that I believe favorite books are about wish-fulfillment; a book becomes a favorite because something in you wants to live that life or have that adventure. A favorite author is something different, however. We choose them—or at least I choose mine—not just because of the work, but because the person behind the work seems to understand something secret and essential and foundational about ourselves. In this sense, Alasdair Gray became one of my favorite authors in a scene about forty pages in to Lanark, in the chapter “Mouths”. Before this moment, the action in the book has concerned a man who remembers neither his name nor his history, who arrives by train in an odd, gloomy, urban landscape from which people keep disappearing. He picks the name Lanark off a wall. During a medical examination that’s part of Lanark’s arrival intake, a doctor discovers a small black spot on his elbow, like a scab, and explains that it’s just a bit of dragon hide, nothing to worry about. As the book progresses, the itchy, scabby spot of dragon hide grows. Lanark, depressed in matters of love, takes to his bed. Then this:

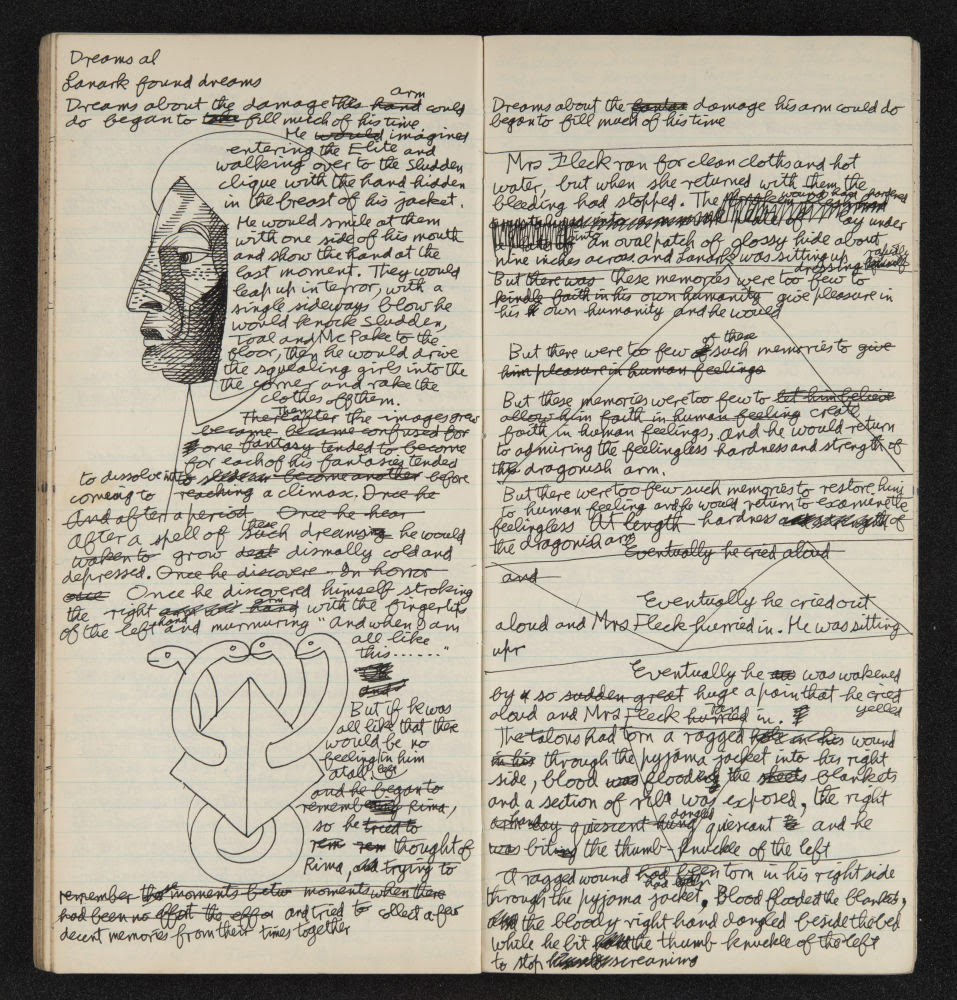

It was a sullen pleasure to remember that the disease spread fastest in sleep. Let it spread! he thought. What else can I cultivate? But when the dragon hide had covered the arm and hand it spread no further, though the length of the limb as a whole increased by six inches. The fingers grew stouter, with a slight web between them, and the nails got longer and more curving. A red point like a rose thorn formed on each knuckle. A similar point, an inch and a half long, grew on the elbow and kept catching the sheets, so he slept with his right arm hanging outside the cover onto the floor. This was no hardship as there was no feeling in it, though it did all he wanted with perfect promptness and sometimes obeyed wishes before he consciously formed them. He would find it holding a glass of water to his lips and only then notice he was thirsty, and on three occasions it hammered the floor until he waked up and Mrs. Fleck came running with a cup of tea. He felt embarrassed and told her to ignore it. She said, “No, no, Lanark my husband had that before he disappeared. You must never ignore it.’”

I read this with a delicious sense of being known. My earliest memory of awareness of my own body is from sitting in the backseat of our family car with my knees up. I must have been wearing shorts or a swimsuit, and when I looked down I saw a pitted and sagging lump of flesh attached to my hip, lolling onto the seat. I was probably 11 or 12. What is that?! I thought something was wrong. It was my own body, but horribly distended, and it had silver stretch-lines in it, like worms. I had to check to see if my other hip looked the same, and when I saw that it did, I realized that I’d gotten fat without noticing it, and that nothing would ever be the same again.

That I wasn’t actually fat, and that fatness equaled doom in my 1980s girlhood milieu is a sad but different story. The part that matters is that my very first memory of knowing I had a body is entwined with a sense of the body’s horrible transformations. The length of the limb as a whole increased by six inches… on three occasions it hammered the floor until he waked up… Somehow, in my heart of hearts, I know just what that feels like. Gray’s understanding has always felt consoling and liberating to me. Our ailments, depicted in his imaginative splendor, became an arena of potential freedom instead of one of doom.

Alasdair Gray, in his own humorous self-description, was a “fat, spectacled, balding, increasingly old Glasgow pedestrian.” I’ll add that he was fair-skinned and not very tall, with small, clear, blue eyes and a crazy nest of hair, ginger in his younger years and then white. I arrived in Glasgow to meet him with a tape recorder (an actual tape recorder, as a backup to my phone) and a list of questions, determined to keep to myself the belief that Gray should love me. The writer as a human being will never be able to satisfy the reader who wants to feel known, and I was old enough to not expect it.

I met him three times at his ground-floor apartment in a beautiful old townhouse in Glasgow’s university district. The flat had two rooms and a kitchen so utilitarian it seemed from a previous generation. We sat in the back, at a table by a window overlooking a garden, in a room that had otherwise been emptied save for a hospital bed outfitted with jaunty nautical sheets. The walls were lined with Gray’s paintings. He wore soft clothing, on one day gray jersey pants, on another a blue sweater, and seemed physically fragile, but he spoke in brilliant and exhausting torrents, leaping from one idea to another. The transcripts in many places are unintelligible to me, including those where he lapsed into old English, or seemed to be quoting from memory. At one point, early on, he exclaimed, “Oh God! I’m afraid you’ve come to confer with a man whose mind is crrrrrrumbling with senility [long rolled rrrrrr]” but that was not true. It was the opposite, as if his long life of reading and writing and painting had placed him within another realm, as brilliantly detailed as the land of Unthank in Lanark, in which he roamed freely, occasionally dragging out treasures for the outsider to enjoy.

It is always a struggle to listen for a long time uninterrupted, and Gray’s discursive fluency was majestic and astounding and ultimately produced feelings of desperation, as I listened intently and waited for small moments to break in. I had hoped, of course, that we’d talk, and we did not—I’m fairly certain he made it through three days without knowing my name—but what happened instead was better. I sat with him through his daily routines, watching while he ate his morning oatmeal, prepared by a nurse. I scrambled on the floor to help find books he wanted to refer to, and pushed the chair and rearranged his feet. My raw transcripts contain endless notes on the voices and intonations in which he said things “[very shrill]…[facetious voice]…[raucous laughter]”, and are peppered with dialogs like this:

VS: Do you want me to move you somewhere?

AG: Oh dear. Brakes on, brakes off? And the brake’s off on that side.

VS: The brake’s on on this side.

AG: How do we push it off?

VS: I have no actual…. I don’t necessarily want to mess with it. It’s probably the other way. Here. It’s that. ta-da.

These were small intimacies. But it felt significant to share a moment of frailty with a man who once wrote that “Diseases identify people more accurately than variable factors like height, weight and hair color.“

Gray’s understanding of our bodies was profound—the dragon hide, the well-chronicled eczema and asthma, the pornographic and sadomasochistic sexual fantasies. But what made him truly great was the humor and humanism and humility with which he approached these things. He was reluctant to discuss his own legacy. When I asked about it, I noted, “He flinched, fine wrinkles fanning out across his forehead, and deflected the conversation.” And yet, his legacy lives on vibrantly.

Read our Art of Fiction interview with Alasdair Gray here

Valerie Stivers is a writer based in New York. In her column for the Paris Review, Eat Your Words, she cooks up recipes drawn from the works of various writers.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/37pSBkx

Comments

Post a Comment