Let me tell you something. The eighteenth century was just straight up not a good time for poetry. Of course, there are exceptions; we’re talking about a hundred years (or, if you’re in graduate school, we’re talking about 160 years). Still, the principle is essentially sound. 1700–1800: bad poetry.

Well, “bad.” Better say unreadable. Some inventive genius could probably set up a pay schedule where the big eighteenth-century poets get their fair share of huffin’-and-puffin’ adjectives. But adjectives aside, the desire to read the stuff is small, vanishingly small.

It wasn’t a bad century for prose. Swift, Fielding, Sterne, Johnson, Gibbon, Boswell. Or zoom in close: Have you ever looked at Elizabeth Carter’s translation of Epictetus? Or Mary Wortley Montagu’s letters? Anybody today’d be damn proud to be compared to any of those cats. Whereas, if somebody compares your poetry to that of Thomas Gray, you are being made fun of.

So why in the world do I read eighteenth-century poetry. Am I a pervert? Do I like things that should not be liked? Answer: I’m no different from you, when it comes to taste. The difference between us is I’m interested in escaping my own perspective as to what’s good and bad in poetry. I want to know what in the world those wigged heads saw in Shenstone, Young, Akenside, Lyttleton…

You don’t care about that. You don’t have a whole lot of time for poetry in the first place, let alone stuff nobody’s read in 150 years. Unless … maybe you’re a little bit like me, after all? Maybe you’re afraid the poetry that you yourself are writing—though esteemed and popular now—will one day be a prompt for baffled speculation. “What in the world did those fapoons in the twenty-first century think poetry was for anyway?”

Perhaps you’ve done your turn as poet laureate, and your thoughts are turning to the long view. Are you Collins? Are you going to be Collins?

*

William Collins—“Poor Collins” to his contemporaries. 1721–59: dead, completely incapacitated and insane, at thirty-seven. Author of two tiny books: Persian Eclogues (1742), and Odes on Several Descriptive and Allegorical Subjects (1746, though dated ’47). Book #1, written before the poet was twenty; book #2, before he was twenty-five.

He could read many languages. He went to Oxford. He had a lot of big plans, all his life. He knew some famous people: David Garrick, the actor; James Thomson, the poet. And Dr. Samuel frickin’ Johnson. But Collins never married, and he never got a taste of his coming immortality. Alas, his stuff was not widely read ’til years after his death.

What is his stuff like. Well … mostly turgid and ucky, allegorical. He loves to get down on his knees and pray to … Peace. Or Simplicity. Or other abstractions. There are almost no people in his poems—not even him, usually. The only, only thing a modern reader can get off on is the froo-froo diction/syntax.

If you have any kind of taste for lines like—

With how sad steps, O moon, thou climb’st the skies…

(Sidney)

or

…that night-wandering, pale, and watery star…

(Marlowe)

or

Not only through the lenient air this change delicious breathes…

(Thomson)

—then you are medically certain to like at least a little bit of Collins. For example, look at a couple choice bits from probably his most famous poem (“Ode to Evening”). Here’s the first line (and then some):

If aught of oaten stop or pastoral song may hope, chaste Eve, to soothe thy modest ear…

(By “Eve” he means evening, not Adam’s girlfriend. “Oaten stop” means, like, a shepherd’s flute or something.)

Now go a little bit further down in the same poem:

For when thy folding star arising shows

His paly circlet, at his warning lamp

The fragrant Hours, and elves

Who slept in flowers the day,

And many a nymph who wreathes her brows with sedge

And sheds the freshening dew, and, lovelier still,

The Pensive Pleasures sweet,

Prepare thy shadowy car.

C’mon, that’s hot. If Collins’s poems were full to bursting with lines like the above, you could bet at least a few weirdos would read him through, from time to time. But the poems are not really like that—not enough. So.

Mainly you get a lot of stuff like this classic anthology piece, Collins’s shortest poem, which I give entire:

Ode, Written in the Beginning of the Year 1746

How sleep the brave, who sink to rest

By all our country’s wishes blest!

When Spring, with dewy fingers cold,

Returns to deck their hallowed mould,

She there shall dress a sweeter sod

Than Fancy’s feet have ever trod.

By fairy hands their knell is rung,

By forms unseen their dirge is sung;

There Honour comes, a pilgrim grey,

To bless the turf that wraps their clay,

And Freedom shall awhile repair

To dwell a weeping hermit there!

Nothing wrong with that. It’s good. “Wraps his clay.” But it’s so emphatically normal—impersonal, marmoreal (if I’m using that word correctly), austere. Maybe kinda Roman? I dunno. Anyhow, I’m saying it’s hard to get excited.

*

Let’s pause and look at a poem by a dead American poet, Karl Shapiro. There’s another reputation upon which the sun has gone down—for reasons that will be obvious in a minute.

The poem is unusual in that it figures people from northern India as guardians of culture—a respectable enough manner of being in the world, but one with which the poet sees himself as having broken.

You Call These Poems?

In Hyderabad, city of blinding marble palaces,

White marble university,

A plaything of the Nazim, I read some poetry

By William Carlos Williams, American.

And the educated and the suave Hindus

And the well-dressed Moslems said,

“You call those things poems?

Are those things poems?”

For years I used to write poems myself

That pleased the Moslems and Hindus of culture,

Telling poems in iambic pentameter,

With a masculine inversion in the second foot,

Frozen poems with an ice-pick at the core,

And lots of allusions from other people’s books.

That’s the whole poem. But see, it’s 2020. By this point, we’re all trained to spot the old trick: let the peoples of the East stand for some standard, ambivalence-causing human trait—in this case, canon mongering and the tyrannies of formal poetry. The objection is obvious: ya don’t have to go to Hyderabad to encounter canon mongering. England, in the eighteenth century, was, emphatically, Shapiro’s India. England was Song Dynasty China … was Babylon the Great … and it still is … and so are we.

On the other hand, the thing I like about Shapiro’s poem is he purposely gives Indians a lot of credit. A frozen poem with an ice pick in the center? That actually sounds pretty cool. And indeed it brings us back to Collins—with him you need a little help seeing the ice pick.

*

Ever heard of Lonsdale—Roger Lonsdale? If you have any investment in eighteenth-century studies, you will have encountered the name. According to Wikipedia, he’s still out there somewhere, chewing bread. Must be in eighties.

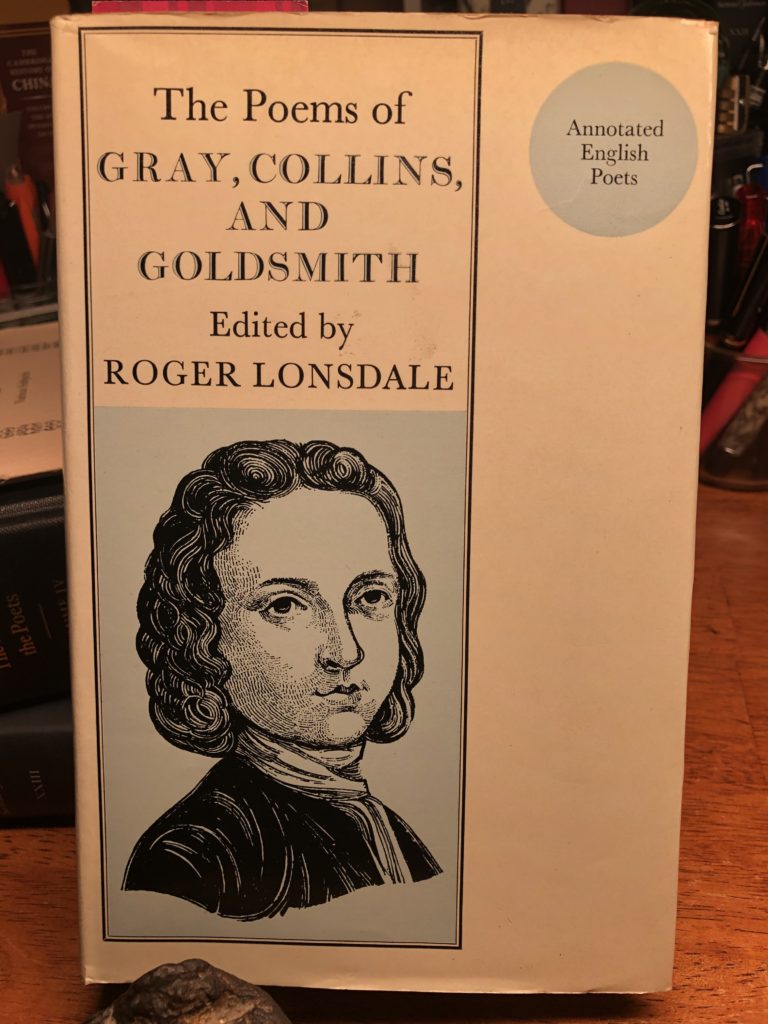

That guy knew more about eighteenth-century poetry than you know about your own life. Witness his supremo-supremo edition of Collins, 1969:

That engraving on the cover is Collins, age fourteen, looking like an illustration out of a 19th-century hygiene pamphlet, warning against the dangers of masturbation.

In the above book, every page is half poetry, half footnotes. For every single line, Lonsdale shows you a-whence Collins pilfered it. Milton’s “Nativity Ode,” Spenser’s Fairie Queene, Pope’s Essay on Man. If Collins lifts a construction, Lonsdale spots it, cites it, explains it—nothing gets by him. And he did it without computers, and he wasn’t even thirty-five when the book came out. I don’t understand how it’s possible for this book to exist.

I remember well, 2002 or 2003, the wild rumor had just reached me and John Maki at the University of Chicago that Lonsdale was about to release an edition of Johnson’s Lives of the Poets in four volumes, from Oxford University Press. Excitement at that level comes but once or twice in a lifetime.

You don’t understand! Lonsdale doing the Lives of the Poets is literally better than the poets themselves coming back to life and explaining their poems. ’Cuz they don’t know what’s important; Lonsdale does.

And yet. To read Collins in the ’69 version, stopping every second like that, is, well, madness. Maybe you have to, once. But if you want to give Collins a fighting chance you need to get a hold of a facsimile of the original Odes and read ’em straight off into a voice recorder. Takes forty minutes; I just did it, this week. Then you play it back when you’re doing your copperplate calligraphy. You start to develop preferences… “Ode on the Passions”—overrated. “The Manners. An Ode”—interesting! And so on.

*

Speaking of Johnson, here’s a notorious paragraph from his “Life of Collins” (1781):

To what I have formerly said of his writings may be added, that his diction was often harsh, unskilfully laboured, and injudiciously selected. He affected the obsolete when it was not worthy of revival; and he puts his words out of the common order, seeming to think, with some later candidates for fame, that not to write prose is certainly to write poetry. His lines commonly are of slow motion, clogged and impeded with clusters of consonants. As men are often esteemed who cannot be loved, so the poetry of Collins may sometimes extort praise when it gives little pleasure.

When Sir Egerton Brydges read that for the first time, as a young man, he shat the bed with rage. Fifty years later he was still so mad he wrote an essay (thirty-one pages in the copy I have), basically saying Johnson had no soul, no feelings, and that Collins compares favorably to virtually every other poet who ever lived, including Aeschylus and Euripides. I’m exaggerating only slightly. The critic really does come off unhinged, reminding me of Walter Bronson’s comment (1898), excusing the ecstasy of one of Collins’s early reviewers: “If this is not criticism, at least it is rapture.”

Just the same, Johnson’s strictures will seem justified to most modern enquirers. He often felt his contemporaries went too far with the decorations, and he was no fan of far-fetched diction like “oaten stop.” In this way, Johnson’s seems like a now-a-go-go mentality; Collins and Egerton seem like fossils. But how can these pre-Romantics seem superannuated, while the Supreme Dictator of Augustan Everything seem like us??

Answer: Because we are everybody, and everybody is us. And this is why we must go on reading forbidding poetry.

We are Hyperboreans: nothing must be forbidden to us.

Anthony Madrid lives in Victoria, Texas. His second book is Try Never. He is a correspondent for the Daily.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/38MzS3q

Comments

Post a Comment