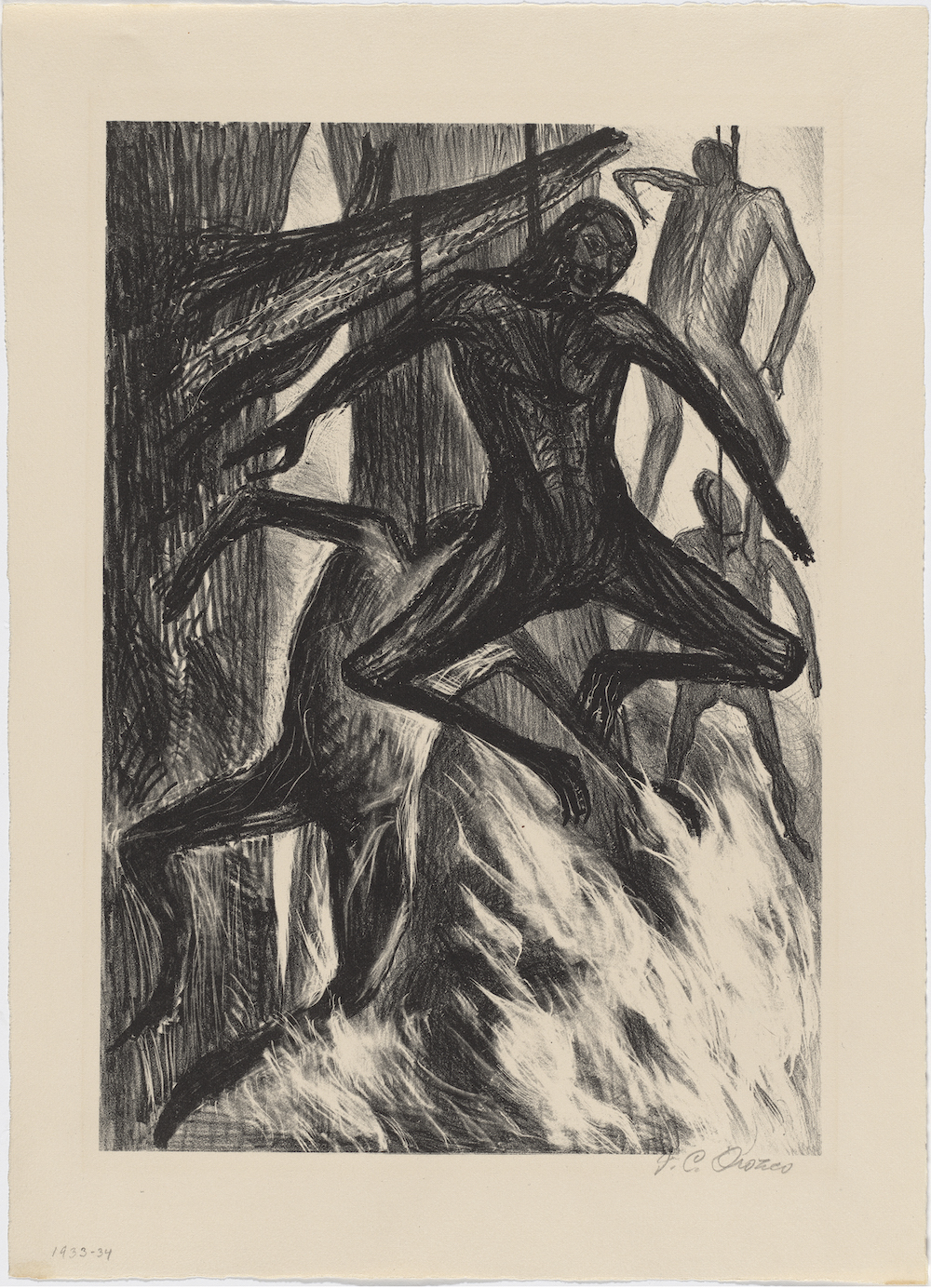

José Clemente Orozco, The Hanged Men from The American Scene, no. 1, 1933–34, published 1935. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SOMAAP, Mexico City.

Who were these bloated neutered monsters hanging in the branches, who become the branches, the forest, barklike limbs, truncated, cut down, howling, angled, parched, rocked by the wind-kicked flames that lick, then tickle, then singe, then engulf?

Why so many here in such disarray of splay? Who is the victor? Who wins when the torture is complete, this death upon death? Who gazes upon the eyeless socket, the seedless groin, the voiceless lips that crack under suspicion? What is this thing born guilty before being proved human? How is it able to possess a supernatural capacity to be lazy, shiftless, yet to rape, be conniving, thieving, uppity, unctuous enough to speak, to yell at, scream at, lash out in frustration at your changing rules, your shifting laws, your erased boundaries? How has it deserved this fate? And why will it not die? How are you unable to kill it to your satisfaction?

Erasure, no time for it—is there a crayon black enough to portray the heart of the American Scene? 1935 was also the year of my great-grandfather’s unceremonious Southern death. The drama of the Jim Crow lynch system, medieval in its execution, modern in its speed and dissemination of photos and souvenirs. The laws were simple: to be black, in skin or heritage, is a death sentence. The body that houses the supernatural ailment “nigger” is readily dissolved by the teamwork, rope, and flame of white supremacy. The prize? Skin, kinky blood-matted hair, a severed ear, finger, or penis, a postcard made the night of the “picnic.” Skinned. Cleansed. Sacrificed, but to what bloodthirsty god?

The psychosis apparent to José Clemente Orozco was not unfamiliar territory for the great muralist, who specialized in social commentary and the history of the Americas and thus was not a stranger to violence in all its extremes. The plight of the powerless is universal, the powerless who are aware of their human rights—they are the New Negro. Our old twentieth century ushered in new revolutions of the spirit, and, with them, new forms of suppression, new aesthetic geometries, mass-produced graphic arts to meet mass graphic violence. Impassioned and dispassionate, using colorless and raw lithographic crayon—the tool of the social-realist painter—the work is ready for reproduction, ready to supplement the voice of the imperiled and annihilated.

Where is the moral? The uplift? The right that will meet this apparent wrong? Why does the artist fail to show the heroes in our midst fighting for justice, fighting to legitimize the law? Why does he not expose the perpetrators? The NAACP requested this work for an exhibition on racial violence, so why are we even looking at this? We are the good guys, we would never commit crimes this heinous, we would never fail to recognize the humanity of others, we were victims once, too! We haven’t got a prejudiced bone in our bodies. We detest violence in all its forms, we are pacifists. We chafe at the sight of this image; our arms go numb and stiff. Our skin crawls. Our blood runs cold. Tears fill our eyes and our throats tighten. The flames lick our toes. Our thighs begin to burn, crackle, and stiffen. Our arms extend at angles away from our distended bellies, and we are left hanging.

Kara Walker is best known for her candid investigation of race, gender, sexuality, and violence through silhouetted figures that have appeared in numerous exhibitions worldwide.

Excerpt from Among Others: Blackness at MoMA © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2TMjETN

Comments

Post a Comment