The first time the writer Thomas Wentworth Higginson met Emily Dickinson, he remembered five details about the way she entered the room: her soft step, her breathless voice, her auburn hair, the two daylilies she offered him—and her exquisite white dress.

Dickinson’s white dress has become an emblem of the poet’s brilliance and mystery. When Mabel Loomis Todd moved to Dickinson’s hometown in the 1880s, she gushed about the poet’s attire. “I must tell you about the character of Amherst,” she wrote her parents. “It is a lady whom the people call the Myth … She dresses wholly in white, & her mind is said to be perfectly wonderful.” Jane Wald, the executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum, believes Dickinson began dressing primarily in white in her thirties, and it was common knowledge around town that a white dress was the poet’s preferred article of clothing. Dickinson realized people gossiped about what she wore, and once joked with her cousins, “Won’t you tell ‘the public’ that at present I wear a brown dress with a cape if possible browner, and carry a parasol of the same!”

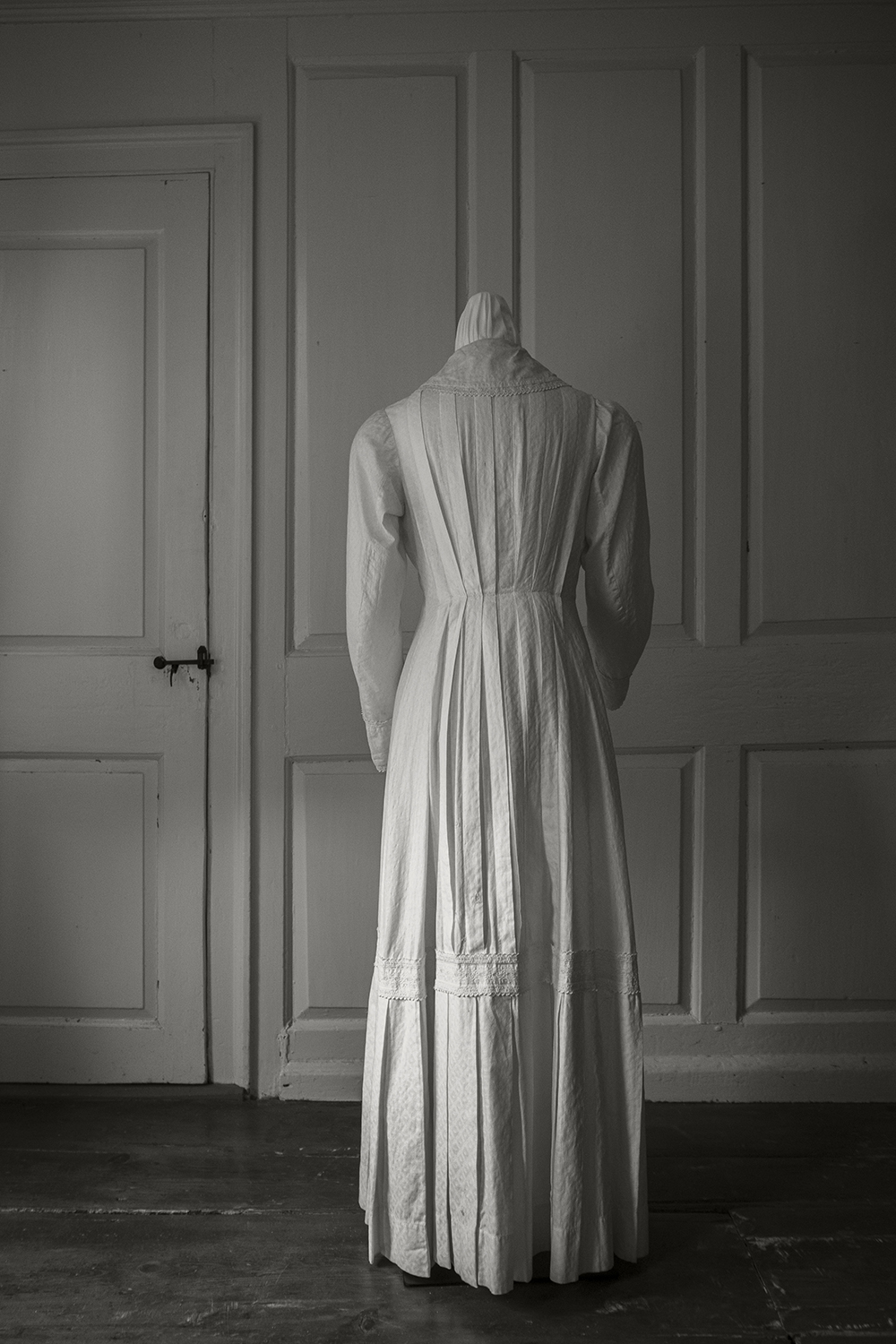

Photo: James Gehrt.

Only a few articles of Dickinson’s clothing have survived: a brown snood, a paisley wrap, a blue shawl, and a single white dress. The dress is unpretentious: cotton piqué, loose fitting with no waistline, featuring a box-pleated flounce at the bottom, twelve mother-of-pearl buttons, a flat collar, and a pocket on the right hip. More than fourteen yards of embroidered lace edge the collar, cuffs, pleats, and pocket. The surviving dress is typical of an inexpensive house garment of the late 1870s or early 1880s and was most likely worn during the last years of the poet’s life. Known as a “wrapper,” it was casual clothing for home and not for social occasions. Stitches indicate it was made on a sewing machine with some handwork. Comfortable and easy to clean, it did not require a corset.

No one talks much about Dickinson’s brown snood, but speculation concerning the poet’s white dress abounds. There are reasons for that, of course. Some of Dickinson’s most memorable poems reference white. “A solemn thing – it was – I said -/ A Woman – white – to be-”; “Dare you see a Soul at the ‘White Heat’?”; Mine – by the Right of the White Election!” Her letters also evoke the color. As a young woman, she imagined her own death scene, “eyes shut and a little white gown on, a snowdrop on my breast.” A decade later, in one of her most mysterious letters, Dickinson wrote to an unidentified Master, asking, “What would you do with me if I came ‘in white’?” Critics contend Dickinson’s white dress might suggest renunciation, purity, spiritual devotion, escape from the daily world, or fierce dedication to art. No single rationale has stuck. In justifying her reluctance to publish, Dickinson once remarked, “My barefoot rank is better.” Perhaps the dress is her barefoot fashion statement.

While preparing my new book, These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, I asked the photographer James Gehrt to take pictures of Dickinson’s white dress at the Amherst Historical Society. For someone who wrote, “The Soul selects her own Society,” Emily Dickinson is everywhere in today’s Amherst. Her portrait is on a utility box in the center of town, a local bakery uses her gingerbread recipe, and visitors regularly leave items at the poet’s grave: notes, coins, and recently a soggy copy of Dante’s Inferno.

The afternoon we shot the photos, Marianne Curling, the curator of the Amherst History Museum, helped James lift the form supporting Dickinson’s dress out of its archival case. Once the dress was upright, James began taking close-ups of the collar, the cuffs, and that pocket—just the right size for a pencil and paper. It was late in the afternoon, and the light was lovely in the museum, one of the oldest houses in Amherst. With Marianne’s help, James carefully moved the form. “Be careful with her,” I heard myself saying. Later on, James positioned the garment’s arms to simulate motion. “I want to see if we can make her move,” he said. All of us that day used personal pronouns to refer to the dress—not “it” but “her,” as if Emily Dickinson were still inhabiting the dress and moving with her own soft step.

Before Higginson met Emily Dickinson that auspicious day, he confessed that he could not always understand her. “Sometimes I take out your letters & verses, dear friend, and when I feel their strange power, it is not strange that I find it hard to write & that long months pass. I have the greatest desire to see you, always feeling that perhaps if I could once take you by the hand I might be something to you; but till then you only enshroud yourself in this fiery mist & I cannot reach you, but only rejoice in the rare sparkles of light.”

Emily Dickinson’s white dress is significant because it is so personal, so intimate, a literal embodiment of who she was. But like the poet herself, the white dress is also inscrutable—more a glint than a conclusion. The dress stayed in Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s mind because it was like those rare sparkles of light—blinding, transitory, and elusive. Is it any wonder? Evanescence was Dickinson’s stock-in-trade. Her poems freeze life’s fleeting moment with startling clarity.

James’s photographs of Dickinson’s white dress capture the poet’s weightless energy and airy restlessness. They reveal something else, too—about both the poet and her poems. Dickinson’s a sly one. She will always be furtive. Always here and gone. There is dash and vanish to everything about her. Just when you think you have her, she slips out of sight.

Martha Ackmann, author of Curveball and The Mercury 13, writes about women who have changed America. The recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship, Ackmann taught a popular seminar on Dickinson at Mount Holyoke College and lives in western Massachusetts. Her latest book, These Fevered Days: Ten Pivotal Moments in the Making of Emily Dickinson, is out this week from W. W. Norton.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/39bau7W

Comments

Post a Comment