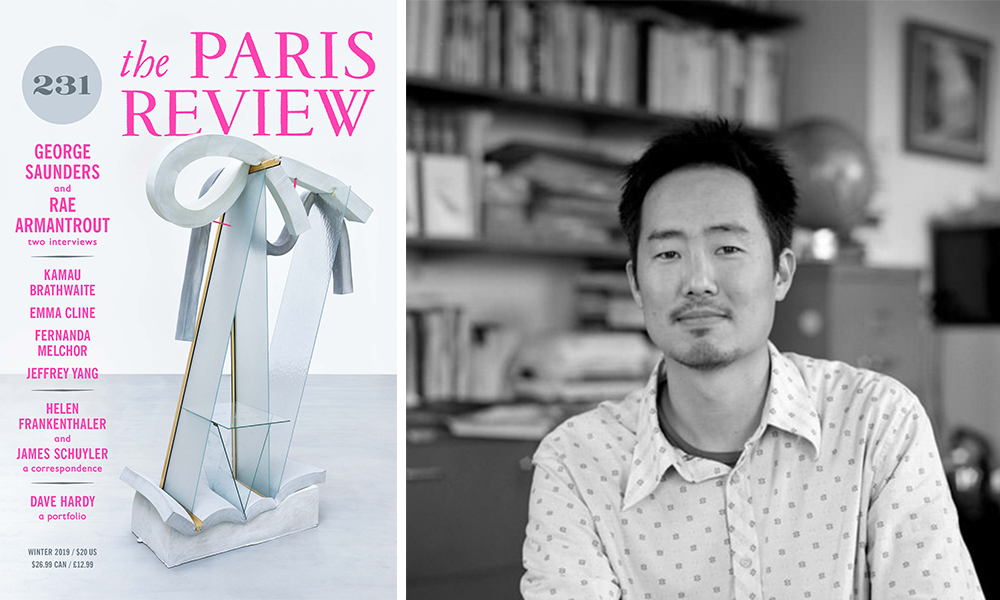

On an overcast Friday this past January, I rode the Metro-North up the Hudson to meet Jeffrey Yang at Dia:Beacon. Yang’s wife is a docent there, and the couple has lived in the town of Beacon, New York, for the past fifteen years. His poem in our Winter issue, “Ancestors,” centers around an exhibition at a gallery in Seoul, South Korea, and the piece made me curious about his work as it overlaps with visual art. When I asked Yang if he might show me one or two of his favorites at Dia before we sat down to talk, my request was met tenfold. We embarked on a comprehensive tour: Dorothea Rockburne’s complex mathematical concepts alchemized through abstract, geometric installations; Richard Serra’s heavy, leaning sculptures of steel; the minimalist reimagining of a book of hours by On Kawara (who Yang recently wrote about here). The pieces that he found exciting were as aesthetically diverse as his poetry.

The world of a Jeffrey Yang poem is eclectically populated. His abecedarian debut collection, An Aquarium, is a taxonomy of aquatic life that incorporates characters from Aristotle to Emporer Ingyo. His most recent collection, Hey, Marfa, takes the eponymous Texan city (coincidentally home to Donald Judd, Dia:Beacon darling) as its subject, and examines the strange transient nature of the city’s history alongside architectural sketches by Rackstraw Downes. In between, he edited the collection Birds, Beasts, and Seas, a seventy-fifth-anniversary tome of poetry from the New Directions archives, and he has translated work by Liu Xaiobo, Su Shi, and Ahmatjan Osman.

Yang is warm and familiar. For every insight into a piece we were looking at, he had a humorous anecdote about Dia:Beacon—he was serious about art without solemnity. After our conversation, he walked with me to town to pick up a sandwich and then saw me and my lunch onto the train. In his career and his process, Yang has pursued his interests without expectation, with the simple faith that they will lead him where he is meant to be going. And to all accounts, they have.

INTERVIEWER

What were your first forays into poetry like?

YANG

I probably started with Chinese poetry, because both my sister and I went to a Chinese school on Saturdays, and we were required to memorize and recite poems. I remember having some children’s poetry anthologies, too, and enjoying the rhythm and the music of those poems.

At University of California, San Diego, there was a pretty experimental literature department. I took one of my first writing classes with Carla Harryman, who was visiting. Melvyn Freilicher, Fanny Howe, Rae Armantrout, Wai-lim Yip, Jerome Rothenberg, Quincy Troupe all taught there. Amiri Baraka also taught as a visiting writer. They were all involved in a more avant-garde idea of poetry in different ways. I remember reading the anthology Premonitions published by this press called Kaya, an Asian American press, which was eye-opening for me. I hadn’t heard of most of the poets in that book, and it all felt fresh to me, how they were really pushing the language. It included some of Theresa Cha’s work, which was also performative and visual. I was curious.

INTERVIEWER

Did you know early on that you wanted to be a poet? Did you conceive of yourself as a poet?

YANG

I still have problems with that question, and don’t really know. Which I guess means “No” and “No.” For me, I’m always trying to figure out what poetry can do. I think that keeps it interesting for me. I feel like my approach has stayed somewhat similar to what it was in my high school days, playing with words. At some point later in college, I just knew that I wanted to keep writing. What that was going to look like, or how that was going to figure in my life I hadn’t really thought about. Even upon graduating with degrees in both science and literature, I wasn’t sure what I was going to do. My father died during my last year at UCSD and I just knew I wanted to move to China, to experience life there. I lived in north Jiangsu province for a year and taught English at a chemical engineering school. I kept writing, and reading more—and then poetry just kind of stuck. Coming to New York changed a lot for me as well.

I applied for some M.F.A. programs, and I went to NYU. So that got me to New York. I really wanted to see Jayne Cortez read with her band, the Firespitters. I hadn’t even thought about what I was going to do after. Publishing kind of came by accident, in a way. During graduate school I tutored adults in professional writing and worked at Merkin Concert Hall, which is still there, in the West Sixties, which put on a lot of experimental classical music, along with some jazz and other stuff. I really learned to listen to what was going on in the music. There was a place called Tonic on the Lower East Side. I was there a lot because I lived in the East Village, and, I don’t know, it was just a fun time to try new things with words and writing.

But even after being at NYU, auditing all these different classes as we were only required to be half-time students, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. Again, the compulsion to write kept growing, and that’s how it’s been more or less, ever since college, really. Maybe once I figure out what poetry really is, I’ll stop.

INTERVIEWER

Your work is encyclopedic, it contains various allusions and draws on so many different traditions. Do you do a great deal of research? How do you fit all these pieces together?

YANG

I think it’s a mix. It takes me a while to figure out the form of a book, and once I have the form, then there are poems that are written to fit into that form. Some poems come out of more researched materials, and some of it doesn’t, and arrives from elsewhere, maybe from observations, or maybe a certain narrative space. There’s a series of poems in Hey, Marfa called “Stra” written in the persona of a mysterious figure, as little cluster of poems. Oftentimes one poem will lead to another poem, even if it’s quite different in content. So, especially for that book it was a big mix, too. Some of them also came out of Rackstraw Downes’ paintings and drawings of substations, and others out of seeing the actual substation there in Marfa, or the relationship of that place with Mexico and the border.

INTERVIEWER

With all of these allusions and characters, your poems are made easier by Google. But I wondered if you would rather someone read through them or stop to Google the things they don’t know.

YANG

I like to read a poem for the sound and music, enjoying it, the ideas behind it, the language, and if there’re things I come upon that I’m not sure about, I usually just kind of put those things aside, and later on I’ll eventually look into it. That’s kind of the hope I have for poems that I write as well. I try and listen to what a particular poem wants to have in it, what it wants to be, without worrying too much if it’s all going to be possible to understand. It’s not trying to make something difficult, it’s more about dealing with the difficulties and complexities around us. I mean, I love total simplicity in a poem too, but for me, if that happens, it only happens after a lot of difficulty. This probably comes out of my reading habits, too, I think. I’m a big marginalia person. I like marking up books, and going back to the ones I love when I can. I try to be open about not wanting to understand everything at once.

INTERVIEWER

With marginalia, do you call out things that you might want to use in a poem? Do you collect as you read?

YANG

Oh yeah, for sure, or, marking something that spoke to me in some way. Which doesn’t necessarily mean I intend to use it for something I’m working on, as most of the time it doesn’t. When I go back and reread something, those markings are like a little map of what I loved about the book. And questions I note, too, how one book or passage leads to another. I love that.

INTERVIEWER

You wrote Hey, Marfa while on residency in Texas. When did you realize the collection was going to be about Marfa?

YANG

I initially went out there to translate June Fourth Elegies by Liu Xiaobo. I’d only translated a few poems at that point. I wanted to finish a draft with the time I was given there, and so kept to a really strict daily schedule in Marfa, and was able to come out of it with the draft in hand. But I had no idea while I was there that I was going to write Hey, Marfa.

I really didn’t know until three or four years later, really. I kept resisting it. It was such a strange experience being given that time and space—a true gift. I had never done a residency before, but being out there in that particular desert, something’s definitely going on with the convergence of creativity and the landscape, plus being really near the border. As I started to write certain poems, I also started to read more about the history of the area, and then, at some point, I felt it was going to be a book. It actually first thought it’d be a shorter serial poem and one section of another book, but then it kept spiraling out and morphed into its own thing. Over a few years, I exchanged letters with the artist, Rackstraw Downes—and his paintings and drawings, and sketches, preparatory sketches, of substations and electrical wires running through the desert eventually became part of the book. What Rackstraw was doing with those paintings resonated with me, in terms of working in serial composition, looking closely at the landscape, and seeing more of the details of what was going on, whether it’s through the natural landscape, the history of the place, or how people were living out there. It was a fun project to research and see where it would take me. It really circles out to other interconnected themes and thoughts—here and there, it circles out, beyond the town.

INTERVIEWER

Your personal experience was the inspiration for the poem “Ancestors” in The Paris Review’s winter issue as well. What was the inspiration for that poem?

YANG

That poem centers around an art piece by the Korean artist, Yun Suknam, that I saw in a gallery in Seoul. I’d been invited there by Literature Translation Institute of Korea. New Directions had published a Korean poet, Kim Hyesoon, recently, and I spent a lot of time with her and her translator, the poet Don Mee Choi. It was an amazing time, where I was able to meet a lot of different artists, editors, and writers, and learn a little bit of what the publishing scene is like in Korea. I happened to be there when the exhibition of Yun Suknam’s work was showing. And I was totally blown away by the work. Kim Hyesoon has been good friends with the artist for many years, and one afternoon she said, “Oh, let’s see if she’s home.” And she phoned her and she was, and so we took a bus to another town outside of Seoul where she lived, and we went to another show of her work, ate eel, and visited her studio. “Ancestors” came directly out of seeing her sculptural work We are a matrilineal family. It struck a deep chord in me as ancestors, the idea of ancestors, their living presence, are a deep part of Chinese culture. And ancestor worship a very important part of Chinese tradition for centuries. Not so much for my family in particular, though it’s still there, in our past, and manifests itself in other ways. What do ancestors mean to us? How do they relate to our everyday life? Yun Suknam’s artwork connected so many threads for me.

Yun Suknam, We are matrilineal family, 2018. ©Yun Suknam (Courtesy Hakgojae Gallery, Seoul)

INTERVIEWER

You use Chinese characters in that poem.

YANG

Those characters denote the name of the Yun Suknam’s gallery in Seoul. They’re Chinese characters as traditional Korean borrows from the Chinese. And in Chinese it’s xué gǔ zhāi [學古齋], meaning something like, “Learning Ancientness Studio,” literally, while the deeper meaning of it resonates through the poem, which is learning from an ancient tradition in order to make something new. That, of course, relates directly to Ezra Pound’s idea that was so central to modernism—“making it new.” But what does that mean for us now? How does it relate to how the Chinese culture treats ancestors, venerates ancestors? In Yun Suknam’s sculpture, the ancestors stand forth like spirit tablets; you really feel their wild presence.

INTERVIEWER

It’s an interesting choice, to disrupt the flow of English with those characters.

YANG

I wasn’t sure if I was going to put them there at first, but then it became the hinge of the poem. I also like playing around with the visual nature of poetry, as far it relates to form. It is also a point where you pause in the poem. It seemed to fit in well with the way the lines were running down the page, and becomes a natural part of the visual landscape of the poem, along with all the indents and stanza breaks, a kind of visual translation of the visual sculpture. I’m very interested in the final form a poem assumes—it’s one of the things that makes it so fun—that you’re dealing with these visual aspects of language as well.

INTERVIEWER

You said that when you figure out what poetry is, then you’ll be done writing. But if you had to answer right now, what is poetry, how would you answer?

YANG

How would I try to describe that…I don’t know how I’d define it, really. Or maybe refuse a single definition. But it’s funny as it’s something that I’m always thinking about. And becomes impossible for me to define succinctly. What we read as poetry, what we see as poetry, as lineation and lines and stuff, is really just the tip of the iceberg of what poetry is. I think that’s why we can say something like Moby-Dick is a long poem—you know, you could easily make that argument, and people have. If I was to describe it, I would say, if we’re talking about poetry as language, that there has to be an element of music in it, even if it’s trying to flatten that, or deny that, in a way, along with a depth of meaning. It’s a form that also can be open to any kind of subject, as well. Any discipline can feed into it. I wish I had a neat answer.

INTERVIEWER

No, this is great news! It means you’re going to keep writing poetry.

YANG

I know! I mean, if I actually said it, I’d be like, Oh, that’s it. I’m done! I can finally relax.

Read Jeffrey Yang’s poem “Ancestors” in our Winter issue.

Lauren Kane is a writer who lives in New York. She is the assistant editor at The Paris Review.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2T6trTK

Comments

Post a Comment