Every week, the editors of The Paris Review lift the paywall on a selection of interviews, stories, poems, and more from the magazine’s archive. You can have these unlocked pieces delivered straight to your inbox every Sunday by signing up for the Redux newsletter.

This week at The Paris Review, we’re feeling a little bored. Read on for some literature that answers our need for stimulation: Margaret Drabble’s Art of Fiction interview, Georges Perec’s short story “Between Sleep and Waking,” and Mary Ruefle’s poem “Milk Shake.”

If you enjoy these free interviews, stories, and poems, why not subscribe to The Paris Review and read the entire archive? You’ll also get four new issues of the quarterly delivered straight to your door. And for as long as we’re flattening the curve, The Paris Review will be sending out a new weekly newsletter, The Art of Distance, featuring unlocked archival selections, dispatches from the Daily, and efforts from our peer organizations. Read the second edition here, and then sign up for more.

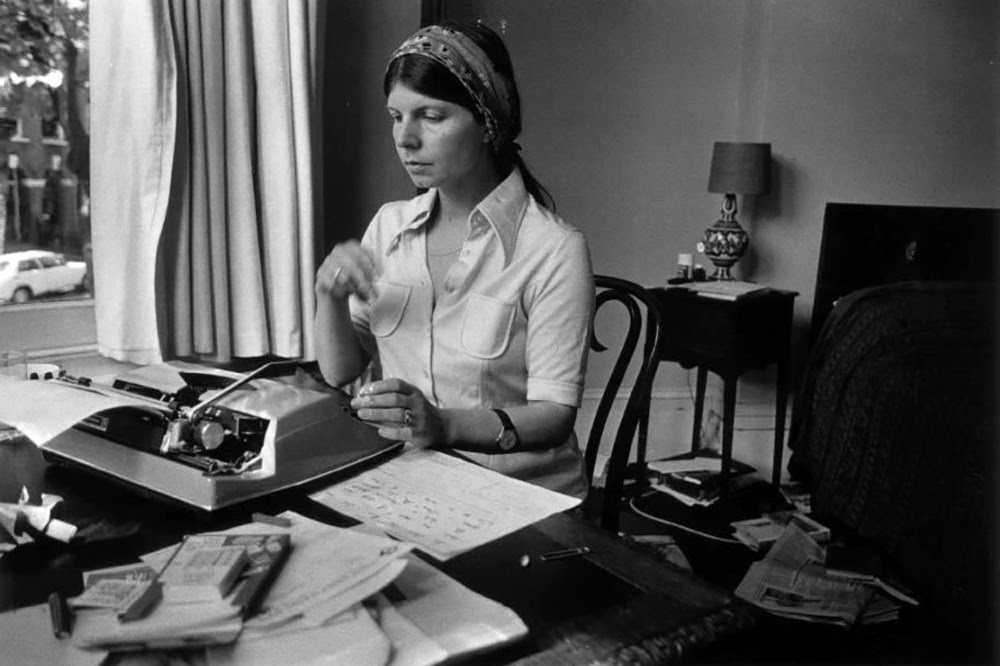

Margaret Drabble, The Art of Fiction No. 70

Issue no. 74 (Fall–Winter 1978)

I wrote my first novel because I just got married and I was living in Stratford-upon-Avon and there was nothing else to do. I was very bored. I had no particular friends there. I’d been very busy up until then—at university, passing examinations—I very nearly took a job that summer and if I had taken a job, I probably wouldn’t have written the book. So in a sense it was accidental. Whether I would have written a novel later, I just don’t know.

Between Sleep and Waking

By Georges Perec

Issue no. 56 (Spring 1973)

For the time being your mind is absorbed by a task that you must perform but that you are unable to define exactly; it seems to be the sort of task that is scarcely important in itself and that perhaps is only the pretext, the opportunity, of making sure you know the rules: you imagine, for example, and this is immediately confirmed, that the task consists of sliding your thumb or even your whole hand onto the pillow. But is doing this really your concern; don’t your years of service, your position in the hierarchy, exempt you from this chore?

Milk Shake

By Mary Ruefle

Issue no. 216 (Spring 2016)

I am never lonely and never bored. Except when I bore myself, which is my definition of loneliness—to bore oneself. It makes a body lonesome, that. Today I am very bored and very lonely. I can think of nothing better to do than grind salt and pepper into my milk shake, which I have been doing since I was thirteen, which was so long ago the very word thirteen has an old-fashioned ring to it, one might as well say Ottoman Empire.

If you like what you read, get a year of The Paris Review—four new issues, plus instant access to everything we’ve ever published.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3bLKykx

Comments

Post a Comment