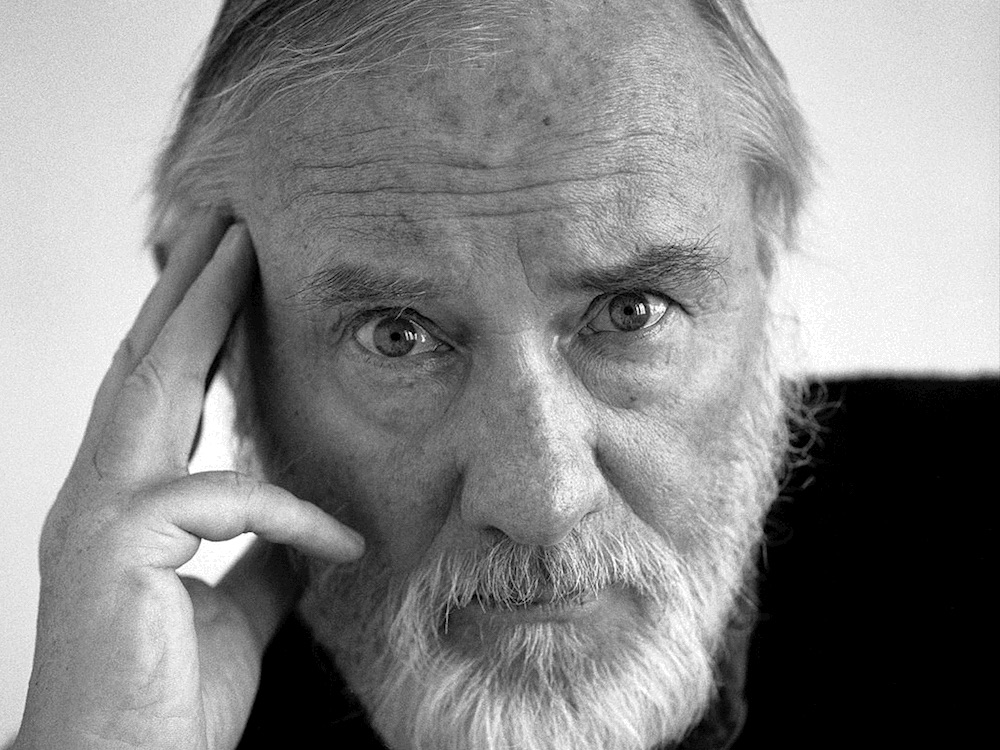

Robert Stone is one of the most powerful and enduring writers of the late twentieth century (also called sometimes the American Century), and in the latter aspect is now thought by many to have come to an ignominious end. Stone’s work chronicled both the peak and the decline of a great many aspects of U.S. world dominance, as practiced abroad and reflected at home. In recounting the struggles of the particular individuals who peopled his imagination, he also told us the story of our time. Stone was an artist, not a reformer, but he had a very unusual ability to engage his fiction with the most urgent social issues of his time and ours, while living in the midst of them, and to do so without artistic compromise.

When Stone mustered out of the navy in the late fifties, the United States had perhaps reached its zenith in terms of economic success and dominance, political hegemony worldwide, and a vibrant and vigorous culture, ripe for exportation in multiple embodiments: from serious literature and high art to B movies, pop music, and Coca-Cola. It seemed a national moment free of self-doubt—although a considerable dysphoria would soon begin to express itself, as the social upheavals of the sixties began. Stone, who did not begin the world from a position of privilege, was quicker than most to see the shadows cast by the rising American star. In his work, he would repeatedly portray those bright aspirations set off by a surrounding darkness that was likely in the end to devour them.

Stone’s novels each capture the zeitgeist of a particular period. A Hall of Mirrors slashes into the underbelly of American racial anxieties as the civil rights movement, and resistance to it, get underway. Dog Soldiers somehow captures the whole spirit of the Vietnam era while barely setting a scene in Vietnam. A Flag for Sunrise delves into the dark side of the Monroe Doctrine, following the most corrupt machinations of American influence into the bloodiest crannies of Central America. Children of Light stages the cocaine-fueled, illusion-rich culture of eighties Hollywood. Outerbridge Reach swings the nineties boom-and-bust stock market cycle by the tail, shaking out its scariest social consequences. Damascus Gate discovers the sinister side of the U.S. engagement with Middle Eastern politics in general and Israel in particular, among other things, as one must always say of any Robert Stone novel—a great many other things. Stone’s fictions are all human stories, first and foremost, driven by characters invested with remarkably rich and dense inner lives—characters we are compelled to recognize as our close cousins. There but for the grace of God (or just good luck, if you prefer) go we.

*

Bob Stone sometimes described himself as a “slothful perfectionist,” though his body of work conveys perfectionism more than sloth. All of his fiction—multifaceted and with unsuspected depths—repays multiple readings, and handsomely. There is little in even the best of contemporary fiction that can claim this quality; however brilliant on the first read, it is not likely to offer fresh insights on a second. The reward Stone offers to the reader is much larger than usual, though he was genuinely hard to please and often found it hard to please himself. He was a conflicted, sometimes tormented personality in both life and art. His disposition was choleric at times; he suffered fools with very small patience, and he confronted the world with the bright, acidic irony of an extraordinarily perceptive, bitterly disappointed idealist. Although Stone was never an autobiographical novelist in the relatively narrow sense that writers like Richard Ford, Saul Bellow, and Ernest Hemingway are, some variation on his own qualities usually gets projected onto at least one major character in all of his novels (Rheinhardt in A Hall of Mirrors, Holliwell in A Flag for Sunrise, Walker in Children of Light) or sometimes the Stone personality is split between two protagonists (Converse and Hicks in Dog Soldiers, Browne and Strickland in Outerbridge Reach, Brookman and Stack in Death of the Black-Haired Girl). His unusual personality, his restlessness, and his ambition for his work caused him to lead what his widow has called “a hell of an interesting life.”

*

Stone borrowed the title of his fourth novel from a poem by Robert Lowell, and used the entire poem as the epigraph of his first:

“Children of Light”

Our fathers wrung their bread from stocks and stones

And fenced their gardens with the Redmen’s bones;

Embarking from the Nether Land of Holland,

Pilgrims unhouseled by Geneva’s night,

They planted here the Serpent’s seeds of light;

And here the pivoting searchlights probe to shock

The riotous glass houses built on rock,

And candles gutter in a hall of mirrors,

And light is where the landless blood of Cain

Is burning, burning the unburied grain.

Enigmatic, quasi-impenetrable, rich with half-realized, tormented thought, it is not Lowell’s best-known poem, nor his best, but it did serve Stone as a sort of chthonic treasure map for his extraordinary exploration of the grandly ambitious, vexed, and troubled American society we all have shared with him.

Born to a single mother, decades before such situations became socially acceptable, Stone was raised an outsider. Throughout his hardscrabble childhood, he and his mother were each other’s sole allies in a struggle against forces out to separate them for their own good. Young Stone spent time in orphanages when his mother could not keep him; he also logged a good deal of time on New York and Chicago streets. His conflicted relation with the American dream has to do with the fact that it was never his by entitlement.

Stone’s life and work reflect the evolution of America’s sense of itself—from the naive ebullience of the fifties to the tenebrous uncertainties of the post-9/11 twenty-first century—and in this process, Stone’s novels were always just a little ahead of the curve. His childhood left him with the street kid’s hardwired alertness to threat, a preternatural sense of trouble on the way, before it has quite crested the horizon. His first fully realized fiction (an oral performance) was composed to outwit Child Protective Services. He spent four years as a very small boy in a Catholic orphanage in Manhattan, plus a few months in a Booth House shelter in Chicago; these experiences gave him a sense of how such institutions can warp personality. A three-year hitch in the navy he began at age seventeen was a different sort of institutional experience, and in some ways corrective of the ones he had before.

At the end of his military service, Stone returned to New York for a brief run as a newspaperman and college student. Within a year he married, dropped out of school, went with his wife to New Orleans and then to California, where he took up a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University and began writing his first novel, A Hall of Mirrors. During those early West Coast years he fell into the orbit of Ken Kesey, who was then beginning his experiments with LSD. Stone partook with enthusiasm, while resisting the cultish qualities of the Kesey circle. By 1964 he was back in New York with his wife and two children working at various short-term jobs while he finished the novel.

After A Hall of Mirrors was published in 1967, the Stones moved to London where they lived for four years, during which Stone went to Vietnam to gather material for his second book, Dog Soldiers. In 1971 he returned to the United States with a teaching career, first at Princeton and then at Amherst College. Dog Soldiers won the National Book Award in 1975, and the publication of A Flag for Sunrise in 1981 consolidated his reputation as a significant voice of his time.

By midlife, Stone had assimilated into the mainstream of American society as much as serious artists ever do; he was a respected novelist, a college professor, the head of a prosperous middle-class household—quartered in Westport, Connecticut; Block Island; Key West; Sheffield, Massachusetts; and Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The Stones always divided their time among two or more residences, while Stone himself incessantly traveled all over the world, for outdoor activities, research for his books, journalistic assignments, and representation of American letters in other countries, sponsored by various avatars of the U.S. Information Agency. His book contracts grew ever more lucrative as his reputation expanded with the big novels of his peak career, especially Outerbridge Reach and Damascus Gate. Still, he could never entirely shake the financial anxiety his insecure childhood had instilled in him and was always eager to pick up a little extra income through teaching and journalism—distractions from fiction writing that he often seemed to welcome. Dependent on alcohol from his teens, Stone embraced most recreational drugs that came his way, and by the end of the twentieth century his alcohol and prescription narcotic use had begun to wear down his remarkably strong constitution. In the early aughts he rallied; there were several more books he wanted to write and for that he needed to take better care of his health than had been his custom. For a time, he returned to full strength as a writer. Then damage from the smoking habit he’d broken in the eighties caught up with him, and he died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 2015.

Stone’s formal education was incomplete; he was to all intents and purposes an autodidact, and despite the many years he spent in academia, he trafficked very little in received ideas. His outsider’s instincts gave him a longer view of the world of which he had become a part. Each of Stone’s novels confronts a peculiarly disturbing problem of the period in which it is set. His technique of splintering his own personality into several different characters allows him to surround each issue with a circle of penetrating views. A Robert Stone novel is an artistically closed system in which the social issues of a given period play out in an experimental form.

*

I became a devout admirer of Stone’s fiction in the early eighties. We were very slightly acquainted then, and during the nineties got to know each other better. During the last fifteen years of his life we were close friends. We shared, among a few other things, an addictive personality and a vocation for letters. In both cases, his were much stronger than mine.

Madison Smartt Bell is the author of fourteen previous works of fiction, including All Souls’ Rising (a National Book Award finalist), Soldier’s Joy, and Anything Goes. He lives in Baltimore, Maryland, where he teaches in the creative writing program at Goucher College.

From Child of Light, by Madison Smartt Bell. Copyright © 2020 by Madison Smartt Bell. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3d8QBB6

Comments

Post a Comment