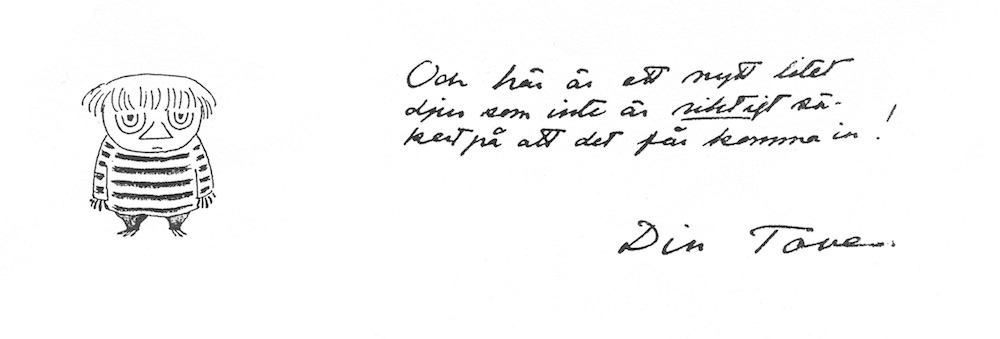

In 1955, after hitting it off at a party in Helsinki, Tove Jansson and the artist Tuulikki Pietilä developed a romance that would last a lifetime. They spent some of the early days of summer 1956 together on the island of Bredskär, where the Jansson family had a summerhouse. The letter below, sent shortly after Pietilä left to teach at an artists’ colony, sees the Moomin creator exploring the dimensions of this new love, recounting the festivities of her uncle Harald’s birthday (“which has traditionally always been a big bash, celebrated at sea”), and drawing “a new little creature that isn’t quite sure if it’s allowed to come in.”

7.10.56 [Bredskär]

Beloved,

Now my adored relations have finally gone to sleep, strewn about in the most unlikely sleeping places, the chatter has died down, the storm too, and I can talk to you.

Thank you for your letter, which felt like a happy hug. Oh yes, my Tuulikki, you have never given me anything but warmth, love, and good cheer.

Isn’t it remarkable, and seriously wonderful, that there’s still not a single shadow between us? And you know what, the best thing of all is that I’m not afraid of the shadows. When they come (as I suppose they must, for all those who care for one another), I think we can maneuver our way through them.

I’m glad you have the advantage of a room to yourself at Korpilahti, so you can just get on with your work and not be disturbed by the cares and intrigues of the colony.

If you write in Finnish, please could you be a dear and use the typewriter; your handwriting’s a bit tricky sometimes. I very much wonder if you could read my last letter at all, Uncle Harald having fallen in the sea with it, along with a consignment of comic strips and a bag of whiskey.

It’s all been intense family living here since they arrived on their sailing boat from Sweden. I ruthlessly go off and draw when I have to, but between times I’m available for household tasks, Bacchanals, child minding, and conversation, whatever turns up. Part of me enjoys it, the other part takes out its frustrations chopping wood. Harald arrived just in time for his birthday, which has traditionally always been a big bash, celebrated at sea.

This year it was magnificently framed by a storm and ended in the traditional joyous whirl of dancing on the rocks, tumbling into pools, and climbing trees. Gentle mother Saga looked after their children for the evening, but in return, all the youngsters from Viken will be coming over to sleep out in tents sometime soon.

The invasions of our beaches are intensifying. Bitti’s in town and will be coming out any time now. After the 20th Uca and Nita. Maybe Kurt. Maybe Maya Vanni. I’m going to try to try to keep my work very separate and leave the cooking to them as much as I can—which is hard, because it’s easier and more natural to do what’s necessary myself.

But I expect it will sort itself out. Presumably there are going to be various strange collisions, but I’m not worried. As regards you and Bitti, it might be much better for you to meet here than in town. The island stays just as beautiful and relaxing, whatever the context in which folk come gadding over the rocks.

One day the whole of Viken came out, Peo as well, bathing was soon in full swing and I had to cook like crazy. It’s good to have the strip cartoons to work on sometimes, I can cope with those however lively my surroundings. I’ve put up the nesting box for the starlings—other than that I’ve been busy with work or socializing. I miss those quiet June days when you were piecing together your mosaic or whittling away at some knotty bit of wood and it was possible to listen, contemplate, and explore how we felt.

On the subject of mosaics, Ham and I gave your “Fishermen” to Harald for his birthday. It was for sale, after all. You said eight, didn’t you?

He was very pleased with it, and it will have a fine place in a home that actually has good taste when it comes to beautiful objects.

Tuulikki, I long to read more in the book of you. I long for you in every way, and I’m more alone with all these people around me than when I was wandering about on my own, thinking of you.

And here is a new little creature that isn’t quite sure if it’s allowed to come in!

Your Tove.

—Translated from the Swedish by Sarah Death

The Finnish writer, artist, and political cartoonist Tove Jansson (1914–2001) is best known for her books about the Moomins, adventurous, amusing cartoon trolls who had much in common with their bohemian, nature-loving author and, it seems, shared many of her family’s traits. She is also the author of eleven novels and short story collections for adults, including The Summer Book and The True Deceiver.

Sarah Death is a prize-winning literary translator, mainly from Swedish, with some forty translated titles to her name.

Excerpt from Letters from Tove, by Tove Jansson, edited by Boel Westin and Helen Svensson, translated from Swedish by Sarah Death (University of Minnesota Press, 2020). Letters from Tove © Tove Jansson / Moomin Characters . Selection, introduction, commentaries © Boel Westin and Helen Svensson. English translation © Sarah Death and Sort of Books. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

. Selection, introduction, commentaries © Boel Westin and Helen Svensson. English translation © Sarah Death and Sort of Books. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3an4qKm

Comments

Post a Comment