In this series, writers present the books they’re finally making time for.

Maybe it is true that books find you when you need them: The Book of Disquiet sat on my shelf for at least a year before I took it down, sometime in February. The hardcover is fat and dense, and the text is, like a drug, rather mood-altering, so I was still working my way through it as things began to change, and am still working through it now, in a world that has come to feel entirely different.

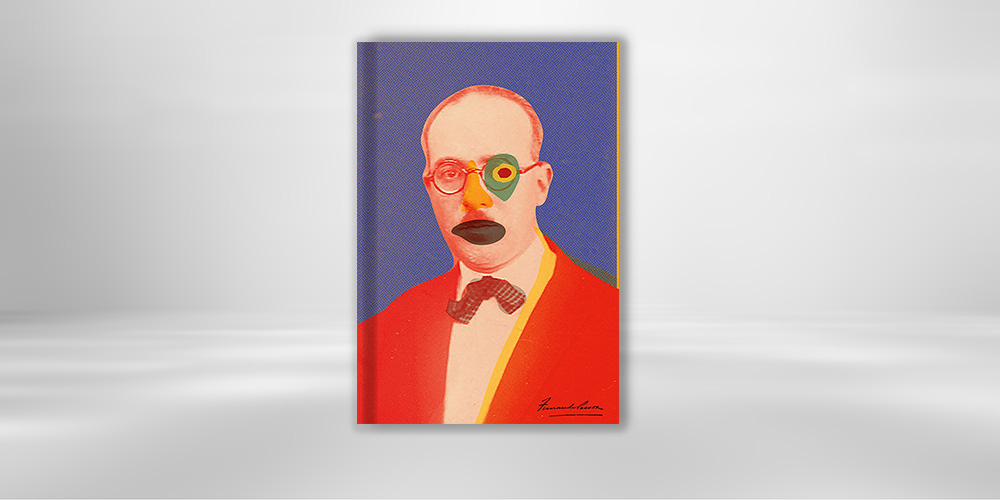

The Book of Disquiet, by the Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, is properly speaking perhaps not a book at all, and I imagine Pessoa would not necessarily be pleased to have his name so prominently affixed to it. Under the orthonym “Fernando Pessoa” he did write an introduction, but he credited the texts themselves to two different authors, his semi-heteronyms “Vicente Guedes” (who “endured his empty life with masterly indifference”) and “Bernardo Soares,” an assistant bookkeeper. The book is made up of fragments of varying length, something like disconnected diary entries. They have been ordered in different ways since they were first collected in 1982, nearly fifty years after Pessoa’s death; in 2017, the Half-Pint Press in London did an edition “typeset by hand and printed by hand on a selection of various ephemera, and housed unbound in a hand-printed box.”

Maybe Pessoa had a plan in mind for his fragments, maybe there was a structure that we just can’t divine—the version I have, Margaret Jull Costa’s 2017 translation of Jerónimo Pizarro’s 2013 edition, is, I think, the first in English to present them as close to chronologically as scholars can figure out—but if any hypothetical order exists I’d rather not know: these are scattered times. Things one didn’t even know one held to or depended on are gone. Rhythm, habit, the rituals that mark and shape the day, something as mindless as the commute that shifts you from one gear to another, none of that registers anymore. There is a frozen-in-place quality to things, an eternal present-ness.

Which is a way of saying that it’s been hard these days for me to find meaning; we are storytelling creatures, but I seem to have lost the plot. I can’t register a story, keep up with a narrative, make sense of any frame. In The Book of Disquiet, though, there seems thus far to be no plot to lose. There are characters and events, but I can find no thread to follow, no causes and effects. Every fragment feels self-contained, its connections to those on either side tenuous at best. As far as I can tell, there is really nothing to be gained from reading the book front to back: you could approach this as bibliomancy, opening at random to find something that speaks to you (no. 27: “To organize our life so that it is a mystery to others, so that those who know us best only unknow us from closer to”). Jull Costa notes that its “incompleteness is enticing, encouraging the reader to make his or her own book out of these fragments.” For me it has been less a building and more a ritual: prayer beads, mantras, a worry stone.

Even more disorienting than the loss of rhythm has been what feels like an extreme shift in perspective. There is a crisis outside, people are terrified, people are fighting for their lives, other people are risking their lives to help them. I am, so far, one of the luckiest, and am counting blessings every morning and crossing my fingers every night—and yet there remain the little things. It feels churlish in these times to be bothered by slow internet, frustrated by a bad hair day, annoyed with a friend over something trivial when I can’t remember the last time I saw him. My heart stops every time I open the news, and somehow I am chewing the same cud I always did.

Not as a distraction but as a counterargument, Pessoa’s book has been, for a couple moments each evening, a helpful companion. To begin with, there is very little of the outside world at all: even when Bernardo Soares is describing how “the dark sky to the south of the Tejo was a sinister black,” the focus of the passage is still Bernardo Soares; the view is always inward. It’s not the melancholy, really, that I’m finding comfort in: it’s the insistence on a self, on the self. Call it what you will, solipsism or self-centeredness, but at the best of times and at the worst of times one is still oneself. And in isolation, one is oneself more than ever. I can’t outrun that, outthink that—and I also can’t be anyone else. So perhaps it is okay, for a little bit of time at night, to think not about what’s happening outside but about something else: “I had a certain talent for friendship, but I never had any friends, either because they never appeared, or because the friendship I had imagined was a mistake made by my dreams. I always lived an isolated life, which became more and more isolated the more I came to know myself.”

Maybe what I’m having trouble with is perspective, balancing a world that has become unrecognizable and unknowable with a me that is yet to adapt. It helps that The Book of Disquiet is also in part a book about how one inhabits one’s city (in this case, Lisbon); yesterday I stumbled upon fragment no. 309, one of Bernardo Soares’s, in which he “daydreams” the journey from the capital to Cascais and back. He is looking forward to watching the landscape and the water, but “on the way there,” he writes, “I lost myself in abstract thoughts, watching, without actually seeing, the waterscapes I was so looking forward to, and on the way back I lost myself in the analysis of those feelings. I would be unable to describe the smallest detail of the trip, the least fragment of what I saw.” New York is still outside my window, I know, but it is transformed (a tent hospital in Central Park, empty subways) and out of reach. Soares’s loss—because it is in some ways a loss—felt like a message. I tried to re-create in my head my favorite walk in the city, in Fort Tryon Park, through the Heather Garden to sit on the Linden Terrace and look across the water at the Palisades. I couldn’t properly recall the small details that mattered—the pattern of the flower beds in the Heather Garden, the weathering of the steps that lead up to the terrace, on which particular bench I last sat. I don’t know when I might next take that walk, but I’d like to believe that when I do, I’ll look more carefully.

Eddie Grace lives in New York.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3emO8n7

Comments

Post a Comment