“I was wakened from my dream of the ruined world by the sound of rain falling slowly onto the dry earth of my place in time.” —Wendell Berry

Spring has no reverence for pandemic. The world is all at once shutting down and opening up —the velocity of change in opposite directions creating a vacuum for each of us.

Last night my nephew was born, and I can’t help but think that he opened into the middle of history.

Nine days before, my cousin Daniel’s body shut down. He had struggled for much of the last decade with addiction and depression. I had been an emotional support for him, perhaps since childhood; we were close our whole lives. He was thirty-three.

My partner and I, and our two young daughters, grow most of our food for the year in the garden, and raise chickens and trout. We heat with wood from the forest in which we live, half an hour from the nearest small town, and have no internet at home. Before this week, we might have taken the phrase “shelter in place” as spiritual instruction. Last week, just before gatherings were prohibited, we travelled to a metropolis for the funeral where, to spare further disaster, we tried our hardest not to hug Daniel’s parents and sister.

My life decisions, like everyone’s, are attempts at joy. Some of the choices my partner and I have been able to make are motivated by the desire to disentangle ourselves from systems whose interconnections rely on hidden suffering. But my hope, and I think the greater truth, is that our decisions are also motivated toward interconnection, toward joy.

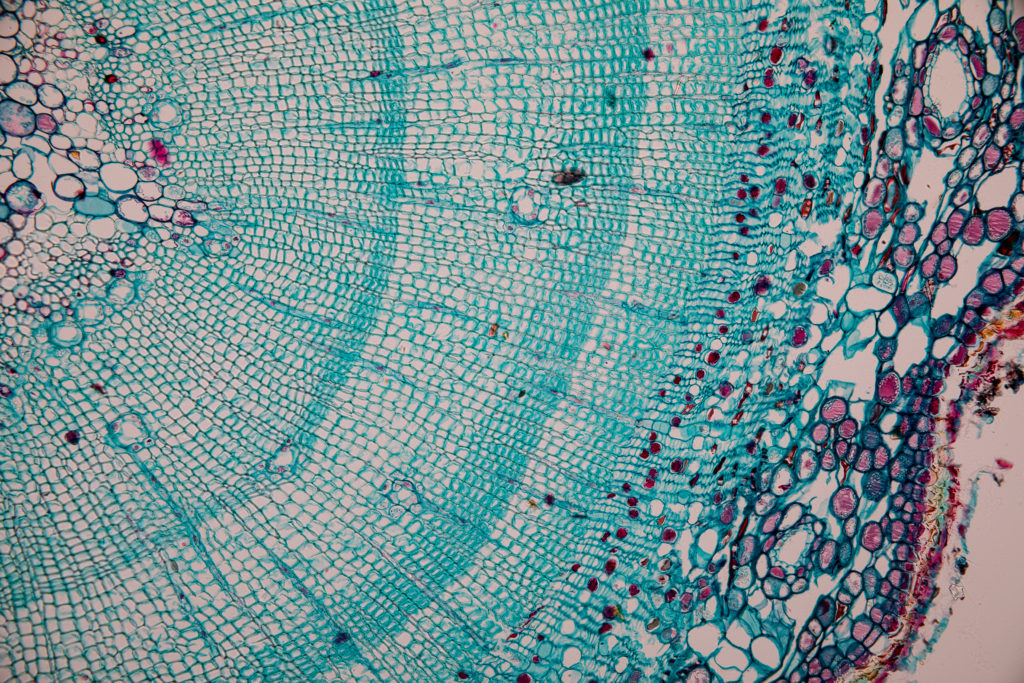

Each of us who pooled our tears at the funeral last week is now in an isolated cell. Each of us in the United States now is in a cell, and countless of us the world over. Prisoners live in cells, but so do monastics. So does all of biological life, isolated and interconnected into the formation of organisms: apple, deer, human being. Cells are discrete but they are not separate; there is the larger body.

The physical world escalates its refrain: nothing is abstract. Neither virus, nor spiritual truth. The garden and woods have been for me a kind of proof of what Thich Nhat Hanh would call interbeing. I believed in interbeing before I depended directly on a garden, but in the garden, the visible proof is delightful: the seed contains the melon, the melon contains the seed. My life is made, quite physically, of the melon—and the apple, and the deer that I eat—of the life of the garden and woods. Without them, I have no body. Without my body, my children have no bodies, no gestation, no milk; nothing to eat. This is true everywhere. The garden and the woods make the lesson slow enough, clear enough for me to grasp. Likewise, pregnancy and nursing clarify patiently that my partner, children, land and I, comprise one another. The slow gestation and weaning of a child—a body inside a body, a body in need of a body—make real the questions Where is it that I end, and the child begins? Where do I begin? And you?

We are interconnected. Right now, we are interconnected by a virus: infinite filaments between us made apparent, connections which are tethers, which are lifelines. Because I’m not abstract, my cell walls are vulnerable, semi-permeable—they are able to give and receive.

Perhaps I love poetry because it joins in the world’s refrain: nothing is abstract. Every memory and feeling is contained by something. It is the fulcrum of metaphor: to relate the intangible to the tangible, the unknown to the known. And it’s the business of the human brain. I think “patriotism” and see something. “Fear” is always hitched to what flashes behind my eyes. I have to keep reminding myself, in this strange time, that I don’t know anything. The brain’s first instinct links experience with expectation, and everything I learn this month hitches to something I think I already know, and takes off.

I love poetry because it translates the abstract to the concrete, the universal to the specific, and then translates it all back again. Poetry locates a specific person in a body, connected, necessarily, to all bodies in all places. It’s a signal between cells that connects the larger body, enables it to feel.

The four of us made it home from the funeral to our place to shelter in. We are here now, planting, working, and watching the garden and the woods, which do not shut down, which still bear investment and return, just as humans do in one another.

It’s from here I send this bottle to the waves. If there is a message in it, it’s that, from here, I see systems that still function. I can see them. The seed, the soil, the streams and springs, the lives of animals and plants that have evolved in response to one another’s needs. They are the systems we are all depending on, from our disparate cells, to provide the still unbelievable miracle that is food, the yet met need that is water. These systems are everywhere, no matter how visible. They are larger and deeper than any of the ones we are watching fall apart, and we’re integral to them—semi-permeable, vulnerable: able to give and receive. Our relationship to these systems, like any relationship that endures, is both responsibility and gift. They are still carrying us. We can still let them.

Daniel is good company to me in all this—I know, I know, no present tense to apply here, and perhaps no “him.” And to whom is it a surprise that grammar’s structure does not match reality’s? Grief is a cell. But Daniel’s company has been real and healing; he laughs often at the things I show him. And this raises for me the question of how much the Daniel I know—the Daniel I sat with, and spoke with—has always been a Daniel within my consciousness. Now, there’s no pretending otherwise. If we all exist like this—in part in the world and in part in one another—then I want to try to take good care of everyone I love from right here. I want to call them all (I’ve been doing some of that. I do have a phone). But, more than that, I want to allow myself the full force of my love, of their individuated loves for me, right here in the place where I shelter them.

As I write, my children run in and out of the room dressed in various states of pajamas and tutus, and it’s only reasonable they should; I am working in their bedroom. My first book, published earlier this week, lies mostly dormant, along with the work of so many people on so many things. My nephew’s early induction kept him only briefly in an otherwise needed hospital. My partner and I are concerned for our tenuous jobs. Life is not without its complications.

I will just keep loving Daniel. That does not change. The hand sanitizer he stockpiled now protects his sister and parents in a time I’m glad he did not have to navigate. I will keep loving the people in my house, full of need and noise. We are together and will not always be. Certainly we will not always be in these forms; the two- and five-year-old faces not here long at all. I am looking at them with eyes that will not always be able to look. They can look now. The calendar, like the jet trails, clearing, everything letting go of where it was going, for a moment.

Here it is morning, and raining. On the other side of this pandemic, there will be celebration in events full of relief and gratitude. We will have much to share with one another. In the crevasse of it, we feel our way through the dark. We dwell with those within us. We keep one another warm until we can climb out. There is so much to receive and give, so much living here, in our cells.

Leah Naomi Green is the author of The More Extravagant Feast(out this month from Greywolf Press), which was selected by Li-Young Lee for the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets. She teaches English and environmental studies at Washington and Lee University, and lives in the Shenandoah Mountains where she, her partner, and their daughters homestead and grow food.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2wBHmZN

Comments

Post a Comment