Contributors from our Spring issue share their favorite recent finds.

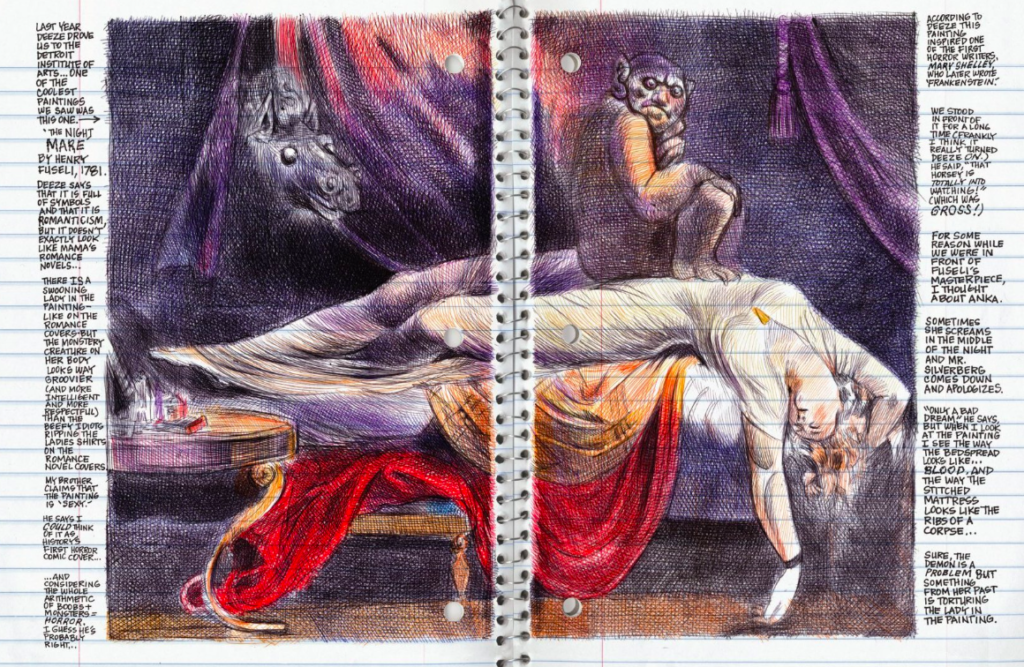

Very late on summer nights when I was a kid, I’d put our crappy pedestal fan on full blast, stick it right beside the couch so that it was refrigerating my face, and quite literally shiver my way through a spooky detective novel of choice. (Electricity was cheaper then.) Reading volume 1 of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters re-creates the goose-bumpy pleasure of an immersive mystery with horrors at every corner. The graphic novel is rendered in atmospheric detail by writer-artist Emil Ferris, using ballpoint pen to capture the fictional diary of Karen Reyes. Karen might be a ten-year-old girl or a budding werewolf—either way, the discomfort of living in an unfamiliar body is palpable on every page. The book is rarely formatted like a traditional multipanel comic. Instead, it spills out, free-form, with full-page panels and long text interludes. It has all the bizarro flotsam of an adolescent brain, too: sketches, taped-up photos, failed math tests, movie posters, covers of horror comics, and, of course, secrets aplenty.

In a very different flavor of diary, Emily Raboteau’s article for The Cut, “This Is How We Live Now,” documents a year of conversations about climate change with friends and family. These small, deeply personal conversations take place at birthdays, dinner tables, housewarming parties; in church basements; and online, all across the span of 2019. Raboteau braids the intimate, humdrum details of these events with observations of a planet in a state of almost unimaginable change: “Carolyn warned me at the breakfast table, where I picked up my grapefruit spoon, that I may have to get used to an inhaler to be able to breathe in spring going forward.” I am in awe of the impossible grace of this project, which dials down the scope of global change to its small-scale vibrations. For someone who needs a cool five or ten years to gain an ounce of insight, the perceptiveness of Raboteau’s climate diaries verges on clairvoyance. —Senaa Ahmad

In the midst of my quarantine in the wilderness of Canada, I have been reading The Religion of Existence: Asceticism in Philosophy from Kierkegaard to Sartre, by Noreen Khawaja, which is complicating all my inherited, unquestioned ideas about the Western contemporary cultural practice of working “the self.” Khawaja finds all the hidden strains of Christianity in existentialist thinking—which, of course, purports to be atheistic—such as the idea that the self must be worked for, must be won, through labor. You aren’t merely yourself but have to win yourself, through conversion, baptism—or, in the case of atheistic moderns, through a struggle for “authenticity,” a struggle that is inherently spiritual in the sense that it can never be accomplished for good. You can’t just say, Great, I’m authentic, on to something else, but have to win this state continually, like the state of holiness in the eyes of God. In a line that I have sent half a dozen friends, who mostly replied, “um I do not understand this at all” or, “I’ll have to think about that!” Khawaja writes, “This work takes on the form of an exercise (askesis), I suggest, to the degree that it is difficult to articulate what the work is good for, what it is supposed to achieve.” Amazing! She is asking, What are we even striving for personal authenticity for? What is being “true to yourself” supposed to win, both in the state of trueness, and if the “trueness” is won? Why have I never stopped and asked that question? Anyway, it turns out not really to be the kind of book you want to be pelleting your friends with random quotes from in the midst of their particular quarantine, but it is undeniably brilliant and mind-altering, and Khawaja has a really direct, light, confident touch as a stylist. I feel like a secret portal is being opened as I read this book, into practices I see everywhere—from the injunction to exercise or to be stylish, to the more profound ways we work on the self; therapy, self-examination, even moving from one romantic relationship to another, in pursuit of—what? And for what? And for whom? —Sheila Heti

Lately, a couple of friends and I have been watching My Brilliant Friend while texting. It’s one of these new-normal ways of staying in touch. We chose this HBO series adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s now-classic Neapolitan novels because we had read and discussed the books together. Like most people who love these books, who are astonished by their gorgeously intimate and complex portrayals of friendship and how identity is formed, I worried about how the world of Lila and Lenù, Naples in the fifties through the seventies, would come through on the screen. One’s own imagination can be tough competition. What I’ve experienced is not just immense relief but immense immersion—different from the one I experienced with the books but just as potent. Lila and Lenù are not exactly who I imagined and yet exactly right. No doubt it helps that Ferrante herself is a consultant on this show, which is now in its second season. The landscapes have a dreamlike quality; Lila and Lenù’s childhood neighborhood looks like a deliberate set. But the tension, violence, love, and rivalry they experience are all too real. My friends and I text one another: how the show is different from the books; what characters look like; our real-time analyses and reactions to whatever unfolds before us. Oh no, someone texts in the middle of a scene, and we all get it. I am in a different time zone from these friends because I moved last year, long before the phrase social distancing. I miss them. But for this hour, while we are all absorbed in this show, I can forget how far away they are. We text while reading the subtitled text on our screens. It’s part correspondence, part journal, part collaboration. Like Lila and Lenù, we know what it is to be filled with so much longing. —Beth Nguyen

In the last week of last year, I decided to read more poems—one every day. Before this, all my daily rituals were prosaic. I was never taught to pray, and so I settled for other, unholy reminders of one day’s continuity with another: toothbrushing, deodorizing, a cup of coffee just so. If you are a certain kind of person, habit can start to seem religious. My boyfriend isn’t this kind of person—I’m the only zealot here—but he agreed to the poems. We alternate days, which is nice: half the time you read and half the time you listen. Sometimes we read in person and other times we send recordings. I hated the recordings at first—a stranger’s tinny voice, supposedly mine—and now that there is no need for them, I love them. I send one from the kitchen to the living room. He sends one from down the block.

The point here isn’t mastery. There are so many poems; three hundred and sixty-five later, there still will be. Maybe it’s something more like discovery. One of the best, so far, is by Linda Gregg, who died last spring, leaving behind half a dozen or so volumes of her work. Some of her most beautiful poems are about loss and refusal, about being alone and being beyond reach. They’re full of horses. “The Defeated” contains a simple lunch, a simple comfort:

I had warm pumpernickel bread, cheese and chicken.

It is sunny outside. I miss you. My head is tired.

John was nice this morning. Already what I remember

most is the happiness of seeing you. Having tea.

Falling asleep. Waking up with you there awake

in the kitchen. It was like being alive twice.

I’ll try to tell you better when I am stronger.

These days, when nearness is literally perilous, maybe there is nothing luckier than this: to know that someone is on the other side of the wall, that nothing was taken away while you were asleep, that life goes on in the next room. For now, we’re still reading, recording, listening. A hundred or so down, a few hundred to go. The sun is bright, our heads are tired. Next year, we think we’ll go back to the beginning, and read them all again. —Clare Sestanovich

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2zGCq6T

Comments

Post a Comment