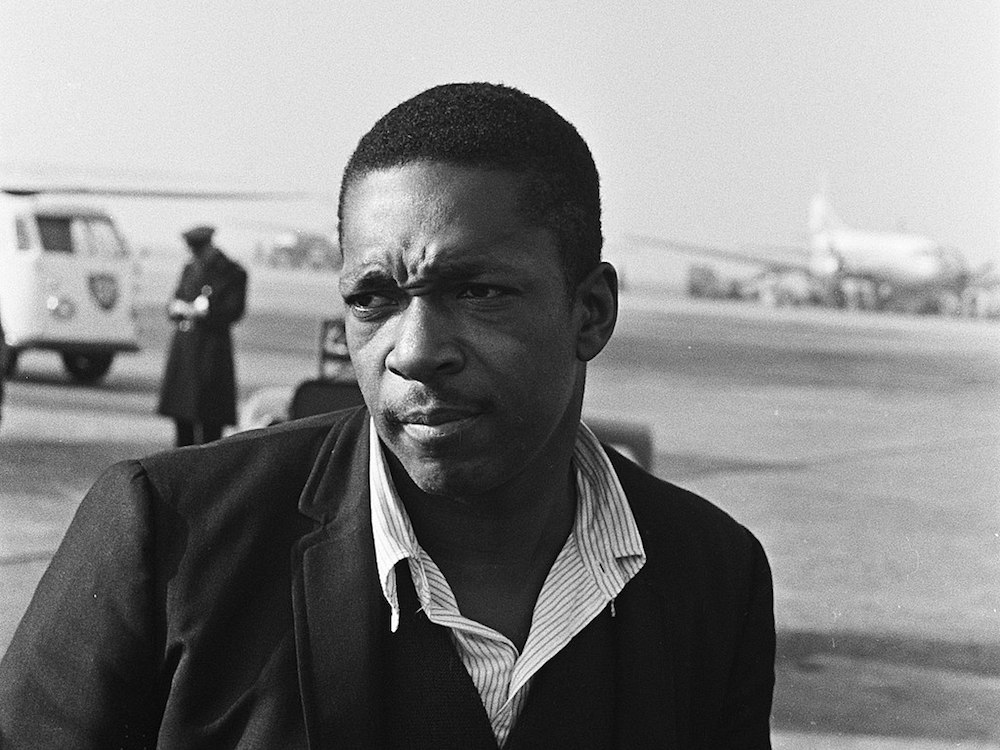

The first thing you hear is McCoy Tyner’s fingers sounding a tremulous minor chord, hovering at the lower end of the piano’s register. It’s an ominous chord, horror movie shit; hearing it you can’t help but see still water suddenly disturbed by something moving beneath it, threatening to surface. Then the sound of John Coltrane’s saxophone writhes on top: mournful, melismatic, menacing. Serpentine. It winds its way toward a theme but always stops just short, repeatedly approaching something like coherence only to turn away at the last moment. It’s a maddening pattern. Coltrane’s playing assumes the qualities of the human voice, sounding almost like a wail or moan, mourning violence that is looming, that is past, that is atmospheric, that will happen again and again and again.

What are we hearing?

It has been hard for me to know what to say regarding George Floyd’s murder, or the uprisings that it has sparked. Sometimes I feel as if there is nothing new to say or write, or nothing that I can say or write that I have not already said and written. We watched George Floyd call out for his mother as a police officer suffocated him to death in broad daylight, in full view of citizens, as other officers facilitated the murder by helping to restrain him. On July 16, 2019, Attorney General William Barr declined to bring charges against Daniel Pantaleo, the officer who suffocated Eric Garner in broad daylight, in full view of citizens, as other officers facilitated the murder by helping to restrain him. That murder took place five years, almost to the exact day, before Barr’s decision. I have run out of words for describing the horror of such regularity. I do not even want to describe the horror for you—what will it gain me to describe it again and again and again? What will it teach you to hear me describe it again and again and again?

What would you even be hearing?

The John Coltrane Quartet’s “Alabama” is a strange song, incongruous with the rest of the album on which it appears. Inserted into Coltrane’s 1964 album Live at Birdland, it’s a studio track that confounds the virtuosic post-bop bliss of the album’s first three tracks, live recordings that include a jittery rendition of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue.” All of that collapses when we reach the sunken melancholy of “Alabama.” We are far, now, from the cascades of sound that Coltrane introduced us to in “Giant Steps,” far from the sonic innovations and precise phrasing he refined in this album’s live recordings. Here, Coltrane’s saxophone sounds hoarse and enfeebled, until it collapses on the threshold of a hole in the ground.

In “Alabama,” Coltrane asks us to bear witness to this hole in the ground, which is also a hole in America’s story, which is also a hole in the heart of black Americans. He wants us to grieve alongside him at this absence. The quartet recorded the track in November 1963, two months after the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, made an absence of four little black girls. When I listen to Coltrane playing over Tyner’s piano I hear smoke rising up from a smoldering crater, mingling with the voices of the dead. He asks us to peer down into the hole, to toss ourselves over into this absence. Just past the one-minute mark, even this funeral dirge collapses in on itself, as Coltrane’s saxophone sinks into a descending arpeggio, coaxing us in.

Then Elvin Jones’s drums enter the fray and Jimmy Garrison begins playing the bass; suddenly we’re on a brisk jaunt that slightly recalls the virtuosity that preceded this track, even though all Coltrane’s sax can muster is squeaking and croaking. We hear Jones mumbling (in delight? Disconcertion?) in the background as if to answer that croak. It all sounds like someone working up a smile in the midst of immense pain, so that he doesn’t disturb the comfort of those around him. And it almost works: we swing and swing until the jaunt comes to an abrupt end, as if the players have remembered why they gathered in the studio that day. We get a second of silence before we find ourselves dropped back down at the beginning of the song, with Tyner’s tremulous keys and Coltrane’s meandering horn. Jones’s and Garrison’s playing disarticulates until they mirror Jones’s mumbling from only a few seconds ago. We’re back at the beginning.

I started listening to and thinking about “Alabama” a lot in the aftermath of Philando Castile’s murder in the summer of 2016, which was reminiscent of the murders of Samuel DuBose, Alton Sterling, Terence Crutcher, Walter Scott, Jamar Clark, Sandra Bland, and countless others. I’d lay down and loop the song through my bedroom speakers because the sonic landscape that Coltrane conjures on the track suggests something about the temporality in which black grief lives, the way that black people are forced to grieve our dead so often that the work of grieving never ends. You don’t even have time to grieve one new absence before the next one arrives. (We hadn’t time to grieve Ahmaud Arbery before we saw the video of Floyd’s murder.) “Alabama” gives this unceasing immersion in grief a form. It’s there in the song’s disconcerting stops and starts, its disarticulated notes, its willingness to abandon virtuosity in favor of a style of playing that is repetitive, diffuse, tentative, and dissonant.

Another thing “Alabama” sounds like: a refusal of articulateness or articulation, a refusal of a tidy Freudian mourning. Coltrane is willing to consider that there might not be any getting out of this hole, no turning this absence into presence, no coherent expression that could make you understand the horror of dying in broad daylight while officers show you all the attention the farmers show Icarus in Bruegel’s Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. No narrative that could make you comprehend a world that uncaring.

Near the song’s end, amid the stormy clatter of Jones’s drums and the ominous keys of Tyner’s piano, Coltrane’s saxophone rises to the high end of its register until it sounds like the screams of a man whose vocal cords are beginning to fray, before Jones’s cymbals take us out into sheets of noise rather than sound. Sometimes, you’d rather scream and storm than have to explain anything at all.

Ismail Muhammad is a writer and critic living in Oakland, where he’s a staff writer for The Millions and contributing editor at ZYZZYVA. His writing has appeared in Slate, the Los Angeles Review of Books, The New Republic, The Nation, and other publications. He’s currently working on a novel about the Great Migration and queer archives of black history.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2ANrd5n

Comments

Post a Comment