In fourth grade, my teacher assigned us a research report on a foreign country. She was a nice white lady. They all were. She said to choose a country we could trace our ancestry to. I was one of her favorites, but when she made that lesson plan, she was not thinking about me. Or Yvonne. We were the Black kids in class.

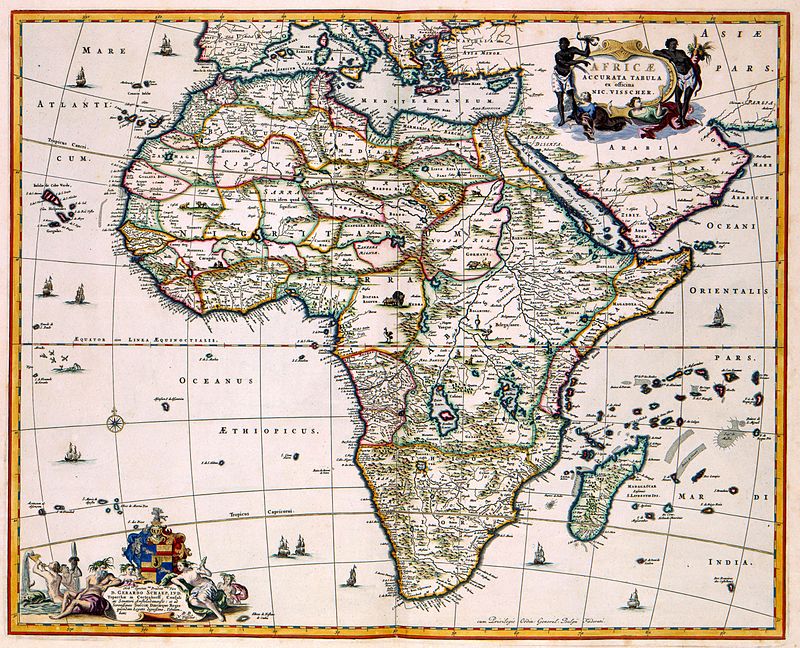

I asked my mom for help after school. She’s Black on her father’s side and Ashkenazi Jewish on her mother’s side; I thought she might get my bubbe on the phone to wax poetic about Eastern Europe. But she didn’t. Nor did she rant about the nerve of the nice white lady whose bright idea this was. If my mom was bitter, she didn’t let it show. She turned that mess into lemonade. She smiled and pulled out the map and we went back to Africa, Garvey on our minds.

Sometimes I learned more Black history in a week at home than I did in a lifetime of Februarys at school. I knew about slavery but I didn’t know about slavery. The information I had to work with was PG, maybe PG-13. Can we ever comprehend that level of unadulterated evil without living through it?

My peers were gripping safety scissors, sketching sauerkraut and four-leaf clovers, spreading glue on the back of a cutout of the Great Wall. I was nine years old, trying not to imagine the skin on my great-great-great-great-great-greats’ backs getting shredded by a braided leather whip that might also catch them behind the ears, where their hair hung in braids the Kardashian-Jenners could only dream of.

I looked down at the map. The men in the Romare Bearden print on the wall looked over my shoulder, too busy jamming on their instruments to tell me the right answer. I just wanted to get an A. I just wanted to be told what to do.

“Mom?”

“We don’t know—they made it so we don’t know. So now we get to pick. Something on the west coast, though. On this curve right here. Let me tell you about Gorée Island.”

She found a shred of autonomy for me, among so much dehumanization. We got to choose. We got to do what our ancestors didn’t.

Senegal. It was arbitrary. It meant everything.

I read the encyclopedia entry on a World Book CD-ROM. Capital: Dakar. Population: 10.28 million. The sun and the sand and the Senegal River and the Atlantic Ocean where they packed us onto boats—but no, there was more to it than that. The fishing and the mining and the Wolof people and the French colonizers and I made my poster or maybe the assignment was to decorate a paper doll.

I gave my presentation and I got my A and I waited to see what Yvonne would do. Imagine my surprise when she chose these United States of America.

I was speechless. She took the easy way out. Coward. It was self-denial, self-hatred. It technically made sense but it didn’t make any damn sense. We were neither indigenous to this land nor citizens of the colonies that would become this nation. Our ancestors were only included as a means to an end, and to me, that didn’t feel like home. I didn’t know what to say to Yvonne, so I said nothing. We were children and we had been given an impossible task.

Only now, years later, can I concede that Yvonne’s response was not cowardly. She claimed her own stake in what some say is the greatest country in history. She undermined the founding fathers by calling attention to the foundation of forced labor on which their glory depended. Our ancestors had lived and fought and sang and died here. They built here with their hands.

I can’t remember Yvonne’s last name or her face but I picture her in two braids, high on each side of her head, bobbles on the ends that clacked like hard candy when she threw her head back and laughed.

This might be a funny story if it weren’t so heinous. It would sting a little less if I could call it ancient history. But just last year, a teacher in New York turned her fifth-grade classroom into a mock slave auction block. Don’t worry—she only confined her Black students to imaginary shackles before she unleashed the White bidders upon them. I suppose real wrought iron would have put her over budget.

Sometimes I want to be a halfway innocent again, lined up with my classmates while we wait to be shepherded to the playground for recess. I want it to be one of those days when I’m standing behind Yvonne—so close I can smell the shea on her skin—knowing that in a few minutes we’ll be playing hopscotch and feeling free.

Mariah Stovall is a literary assistant at Writers House. Her fiction and nonfiction can be found in Poets & Writers, Vol 1. Brooklyn, Literary Hub, HelloGiggles, Joyland, Ho

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/31tdonO

Comments

Post a Comment