In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“This installment of The Art of Distance is inspired by the past week’s #BlackoutBestsellerList campaign, which encouraged book buyers to purchase two books by Black authors in order to fill best-seller lists with Black voices. Unlocked this week are seven pieces from recent issues of The Paris Review by Black writers who have also recently published books. If you enjoy this writing, we hope that you will consider buying these authors’ novels, story collections, and nonfiction works. We wish you a week of meaningful reading and hope you stay safe, sane, and engaged.” —Craig Morgan Teicher, Digital Director

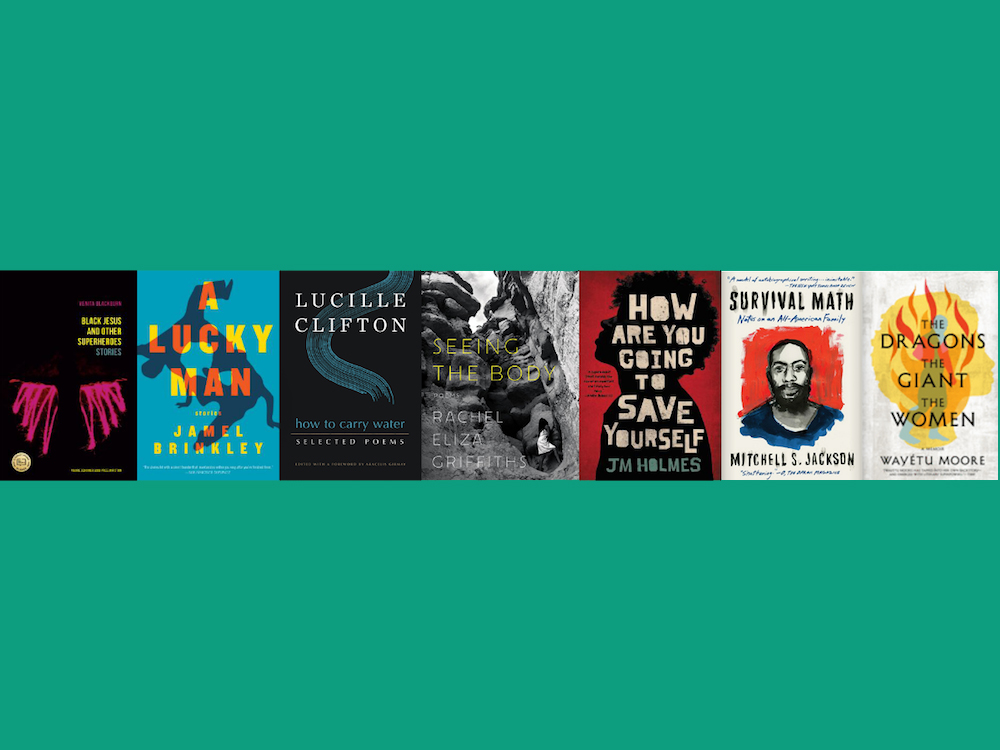

Read these stories, poems, and essays by TPR authors, and then check out their new, recent, and forthcoming works linked below.

Venita Blackburn’s “Fam” (issue no. 226, Fall 2018) is a haunting glimpse into the social media life of a teen whose past is shadowed by family violence. Her debut story collection, Black Jesus and Other Superheroes, won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize for fiction, and Blackburn was a finalist for both the PEN/Bingham Prize for debut fiction and the Young Lions Award from the New York Public Library.

“Witness,” by Jamel Brinkley (issue no. 233, Summer 2020), is a sobering examination of race and health care in America. Brinkley’s story collection A Lucky Man was a finalist for the National Book Award.

Two unpublished poems by Lucille Clifton, “Poem to My Yellow Coat” and “Bouquet,” appear in issue no. 233, Summer 2020. They’re drawn from a group of unpublished poems that will be included in How to Carry Water, a career-spanning selection of Clifton’s work due out in September.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths’s poem “Hunger” (issue no. 232, Spring 2020) is a searing elegy for the poet’s mother that wrestles with and takes inspiration from a kind of magical thinking. The poem comes from her just-published collection of poetry and photography, Seeing the Body.

Told largely in rapid-fire dialogue, J. M. Holmes’s “What’s Wrong with You? What’s Wrong with Me?” (issue no. 221, Summer 2017, and The Paris Review Podcast Episode 16) barrels toward a shocking revelation about racism and sex. The story appears in his first book, How Are You Going to Save Yourself.

Mitchell S. Jackson’s essay “Exodus” (issue no. 226, Fall 2018) begins in “the wilderness of my hometown” and ends at the foot of the stairs of “what would be my new home.” It opens into a story of life marked by violence and addiction that continues in his memoir, Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family, which was named one of NPR’s favorite books of 2019.

The protagonist of Wayétu Moore’s “Gbessa” (issue no. 225, Summer 2018) is deemed a “cursed” child by the people in her town and must suffer their derision and blame for circumstances beyond their control. “Gbessa” became the first chapter of Moore’s debut novel, She Would Be King. Read an excerpt of her new memoir, The Dragons, the Giant, the Women, on the Daily.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2V7AhZU

Comments

Post a Comment