Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems is a sterling one-of-a-kind record of what it meant to be the late great poet Wanda Coleman. I will offer a few comments, but let it be said, in life and in poetry, Wanda Coleman always preferred to speak for herself.

In Wanda’s introduction to her chapbook Greatest Hits 1966–2003, published by Pudding House Press in 2004, she wrote:

Eager to make my mark on the literary landscape, I got busy finding the mentors who would teach me in lieu of the college education I could not afford. As a result, I have developed a style composed of styles sometimes waxing traditional, harking to the neoformalists, but most of my poems are written in a sometimes frenetic, sometimes lyrical free verse, dotted with literary, musical, and cinematic allusions, accented with smatterings of German, Latin, Spanish, and Yiddish, and neologisms, and rife with various cants and jargons, as they capture my interest, from the corporate roundtables to the streets.

First of all: the syntax of that second sentence is breathtaking. Second of all: what could I say to follow that!? Maybe something about my own true introduction to her?

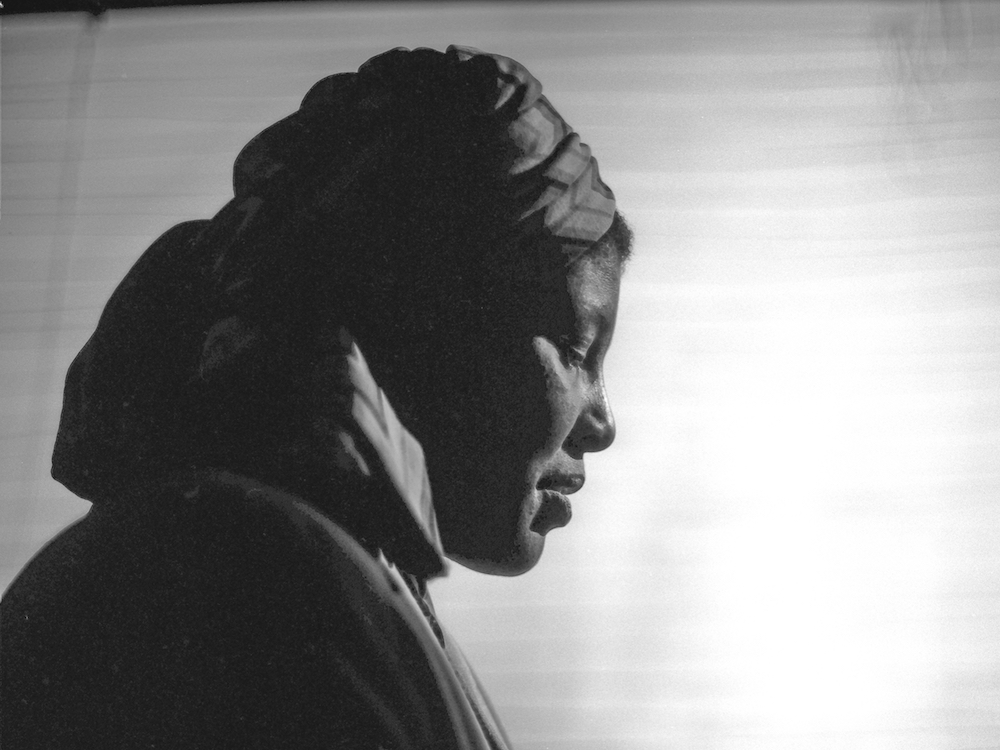

In the summer of 2001, I shared the stage with Wanda at the Schomburg Center for Black Research’s 75th Anniversary Heritage Festival. The reading, “A Nation of Poets: Wordsmiths for a New Millennium,” included Wanda and me, along with Amiri Baraka, Staceyann Chin, Sonia Sanchez, and Patricia Smith. It’s not a very detailed memory. I was too awed to truly pay attention to anybody’s poems (my own included). I mostly only remember the “frenetic, sometimes lyrical” (Neologismic? Languafied?) sound of Wanda’s voice, her towering hair and bangles, her patterned fabrics and big glasses and big wicked laugh. I don’t remember what she read, though I know she was writing some of her best work at the time and finally receiving some long overdue attention. Mercurochrome, the book she published that year, would be a finalist for the 2001 National Book Award in Poetry, and 1998’s Bathwater Wine had received the Lenore Marshall Prize from the Academy of American Poets. But Wanda was still announcing her presence and suspicions.

Upon our first real conversation on a panel at an LA book festival the next year, Wanda “tore me a new one,” as they say. She was a grenade of brilliance, boasts, and braggadocio. She burned and shredded all my platitudes about whatever poetry topic was at hand. She softened only when she understood/believed I was a fan. One of my mentors, a black female poet of Wanda’s generation, recently flatly said, “She was mean.” She could be mean. It was a sharpness she honed over her years outside the care of poetry collectives, coalitions, and institutions. Her poems often record the mood of one who feels exiled, discounted, neglected. Imagine how mean the famously mean Miles Davis might have been had no one taken his horn playing seriously, and you will have a sense of Wanda’s rage. I think some of it was misplaced. She had legions of fans. The actress Amber Tamblyn is a supreme Wanda disciple. Her fans include Yona Harvey, Douglass Kearney, Dorthea Laskey, Tim Seibles, Annie Finch, experimentalists, formalists, feminists, spoken-word artists. She once told me the musician Beck is a big fan. There is no poet, black or otherwise, writing with as much wicked candor and passion.

I have taught her poetry to my students for nearly all of my career. One of my oldest homemade writing exercises asks poets to devise their own American sonnet after looking at Wanda’s American sonnets. Eventually, I tried the exercise myself. I sent my first attempt, a poem entitled “American Sonnet for Wanda C” (from How To Be Drawn, 2015), to Wanda a year or so before her death in 2013. I was imitating Wanda for years before meeting her. “The Things No One Knows Blues” in Hip Logic, my second collection, is a direct nod to her poem “Things Know One Knows” in Bathwater Wine. Yes, she let her guard down when she saw I was a fan. We became friends. I would never say close friends. But we were close poets. Our letters and exchanges concerned nothing but poetry. Her passion for poetry made her sharp, warm, honest. Naturally, I loved her.

Wanda Coleman was a great poet, a real in-the-flesh, flesh-eating poet, who also happened to be a real black woman. Amid a life of single motherhood, multiple marriages, and multiple jobs that included waitress, medical file clerk, and screenwriter, she made poems. She denounced boredom, cowardice, the status quo. Few poets of any stripe write with as much forthrightness about poverty, about literary ambition, about depression, about our violent, fragile passions. “American Sonnet 95” is one of my favorite sonnets by Wanda:

seized by wicked enchantment, i surrendered my song

as i fled for the stars, i saw an earthchild

in a distant hallway, crying out

to his mother, “please don’t go away

and leave us.” he was, i saw, my son. immediately,

i discontinued my flightfrom here, i see the clocktower in a sweep of light,

framed by wild ivy. it pierces all nights to comei haunt these chambers but they belong to cruel churchified insects.

among the books mine go unread, dust-covered.

i write about urban bleeders and breeders, but am

troubled because their tragedies echo mine.at this moment i am sickened by the urge

to smash. my thighs present themselves

stillborn, misshapen wings within me

Wanda’s poems speak for themselves.

In the margin of my secondhand copy of Mad Dog Black Lady, her first full-length collection, published by Black Sparrow Press in 1979, someone wrote: “Her world is a shriek.” The poems do shriek sometimes. In “Wanda in Worry Land,” the refrains “I get scared sometimes” and “I have gone after people” echo the paradoxical vigor at the heart of her poems. They take the forms of aptitude tests, fairy tales, dream journals, and comic-book panels. They combine manifesto and confession, inner and outer indictment, violence and tenderness, satire and sincerity. Her imitations of everyone from Lewis Carroll to Elizabeth Bishop to Sun Ra slip between homage and provocation. Themes and passions recur across the books in series like “Essay on Language,” “Notes of a Cultural Terrorist,” “Letter to My Older Sister,” and especially in the American Sonnets series, which debuted in African Sleeping Sickness in 1990. Commenting on the series in the Adrienne Rich–edited Best American Poetry 1996, Wanda wrote: “In this series of poems I assume my role as fusionist, delight in challenging myself with artful language play. I mock, meditate, imitate, and transform … Ever beneath the off-rhyme, the jokey alliterations, and allusions, lurks the hurt-inspired rage of a soul mining her emotional Ituri.”

All of that. Every poem is an introduction to Wanda Coleman. I keep her poems close because they never cease surprising me. In “Looking for it: An interview,” she says, “I want freedom when I write, I want the freedom to use any kind of language—whatever I feel is appropriate to get the point across.” She never ceases revealing paths to get free.

Terrance Hayes is the author of eight collections of poetry, most recently American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (Penguin Poets, 2018), which received the 2019 Hurston/Wright Legacy Award for poetry. A Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, Hayes is a professor of English at New York University and lives in New York City.

From Wicked Enchantment: Selected Poems (Black Sparrow Press, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Terrance Hayes. “American Sonnet 95” copyright © 2020 by The Estate of Wanda Coleman. Reprinted with the permission of Black Sparrow Press.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2MRpnTB

Comments

Post a Comment