I met Brad Watson in 2004. He was starting a one-year stint as the Grisham Visiting Writer at Ole Miss, where I was an M.F.A. student, and I’d signed up for his workshop. The week before the semester began, I saw him at a bar in town, newly arrived and sitting on a stool by himself. I went up and introduced myself and he looked me over and grinned. His eyes had this way of shining when he found something funny.

“You the one who wrote that weird story with the mannequin?” he asked me.

“I am,” I confessed.

“I enjoyed it,” he said, and picked up his drink. “I like sort of oddball stuff.”

At that point in my life, my glorious and unpublished twenties, I knew only that I wanted to be a good writer, not that I could be. So, this exchange gave me a suspicious confidence. I liked Brad from the start.

After we said goodbye, I walked directly to Square Books, smiling, and bought his debut collection, Last Days of the Dog-Men. I then went back to my apartment to read it. I wish I could tell you that it charmed me as much as he had, but the truth is I was young and jealous and dumb and distrustful of people who’d had so much success early in their career. The book was published by Norton. It won the Sue Kaufman Prize for Fiction. Writers who accomplished these things at first blush angered me back then. They had to have some connection, I always thought, they must be plugged into some secret writer society in New York for these things to happen. And here I was living in Mississippi, in an odd circular apartment complex the locals called Ewok Village. What chance did I have?

All I knew for sure was that his stories were set in the South, like mine aimed to be, and because of this I felt a bit competitive with him back in my idiot days. I didn’t want to be just another Southern writer, though, and when I realized the title story of his collection was about men out fishing, shooting at snakes and turtles, as so many Southern stories seem to be, I rolled my eyes. I decided this Watson guy, with all his critical acclaim, would be my benchmark. Whatever he achieved, I told myself, I would top it. He, of course, already had a collection and a novel out at that point, whereas I’d not published a single thing of note. Still, he was older than me. I figured I had a decade to catch him.

Little did I know the sort of genius I was up against.

In addition to the workshop, I signed up for Watson’s take on Form, Craft, and Influence, a course in which the professor chose books they considered formative to their own aesthetic or style. Barry Hannah taught Kafka’s The Trial in his version; Tom Franklin taught Rick Bass’s The Watch. Brad’s syllabus, however, remains to this day one of the most eclectic I have ever seen. He assigned things like Michael Ondaatje’s verse novel The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, Kate Jennings’s Snake, Richard Brautigan’s Willard and His Bowling Trophies, and The Lover by Marguerite Duras, among others. For a writer who grew up in the South, riding the dirt roads of Faulkner and O’Connor since undergrad, it was a bewildering volley of new voices and settings.

Yet Brad’s interest in these books was so contagious that my friends and I found ourselves behaving oddly, like reading passages of Lars Gustafson’s The Death of a Beekeeper, which he’d also assigned, to each other on a Saturday night instead of going to the bar. It wasn’t until midway through the semester that we began to realize what these disparate books had in common. They pushed boundaries, yes. They were beautifully written, of course. But, what seemed to connect them all for Brad was a thread of deep sadness woven throughout each narrative.

Around this same time, Brad had also grown more morose. There was a woman in Texas named Nell that he loved, it turned out, as well as two sons from a previous marriage. He was thankful for the paycheck in Oxford but missed these people too much for his heart’s liking. The loneliness got to him. In those days, the Grisham Visiting Writer lived in a nice house right off the town square in Oxford, and Brad took to holding his classes there. On many nights, these classes were cheerful and fine, but on others we would show up to the house to find Brad staring at a fire in the fireplace, though it wasn’t cold out. He would conduct the class as he was paid to do, kind and thoughtful as ever, but it was obvious his heart wasn’t with us.

*

After fancying myself too cutting edge for Last Days of the Dog-Men, I finally read Brad’s first novel, The Heaven of Mercury, and realized what a fool I’d been. This novel, a finalist for the National Book Award in 2002, does everything a Southern Gothic novel is supposed to do, everything I thought I was supposed to be subverting, but does it in such a sublime and well-crafted way that all the knobs on my amp had to be readjusted. Everything that could have been a Southern cliché—small town characters named Finus and Creasie and Birdie, a necrophiliac, an undertaker, a medicine woman, even a ghost—all feel totally fresh and unique. And the factor that differentiates these characters and their stereotypes, of course, is Brad. He never took a character lightly.

Finus is not just some eighty-nine-year-old coot but, instead, an obituary writer and lover of Wordsworth who recognizes his only moment of transcendence had been when he was a young boy and accidentally saw a girl, whose heart he’d never be able to win, do a cartwheel in the nude. Such a long stretch of years between him and that moment of joy and soon the novel, rotating through strange and empathetic characters almost kaleidoscopically, reveals itself to be the very thing Brad had been trying to show us in class. It is a beautifully written, boundary-pushing meditation on love, loss, and sadness, like nearly everything he’d assigned.

I felt something in me click.

The way to make your own path as a writer, I began to understand, was not to discount every literary convention you came across, but to use it, instead, to your advantage. You don’t ignore Faulkner and Flannery, Hurston and Welty. You build upon them to create a new voice. A new Brad Watson. This can’t be done by reading only the writers you most want to emulate, but by reading those you may seem, on the surface, to have nothing in common with. As obvious as this should be, it wasn’t to me then, and Brad cracked it open.

*

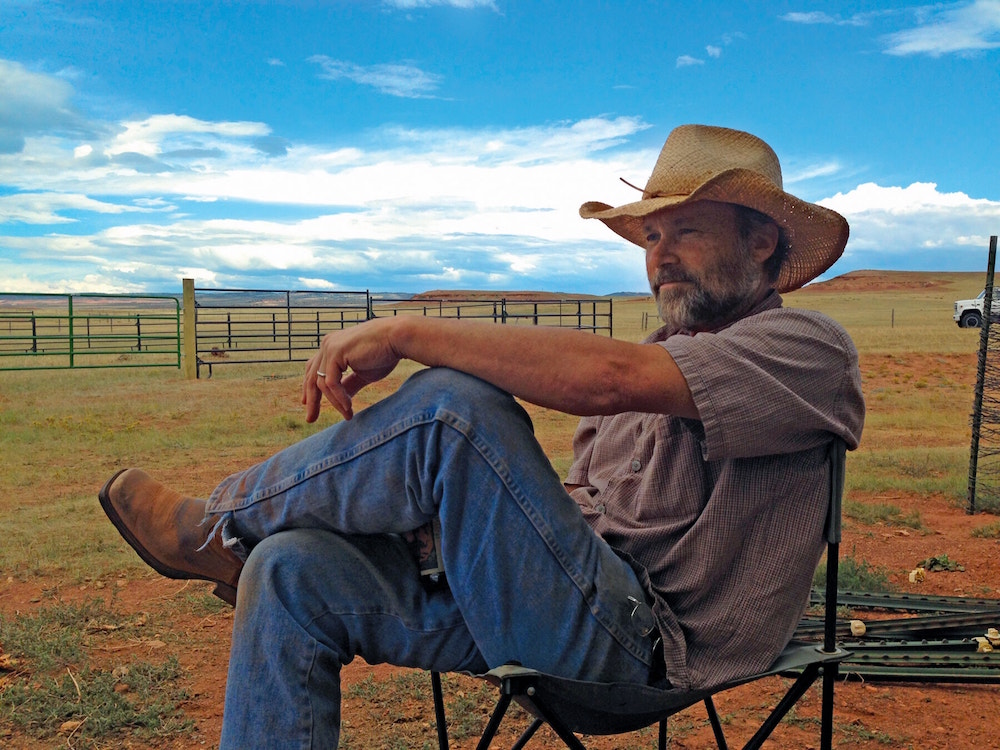

Brad left Oxford the next summer, and we kept in touch sporadically. He soon landed a great job in Wyoming and, in these years away from one another, my admiration for his work grew. I read the stories he was publishing in The New Yorker, Ecotone, and Granta, each one so different, strange, yet so undeniably his that I came to recognize what was afoot. Brad Watson was quietly becoming one of the best writers in America.

This was confirmed for me with his next collection, Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives, which contains stories so distilled and original that I felt nervous to talk to him. What do you say, I wonder, to a person so talented? I began handing out stories like “Alamo Plaza” and “Visitation” to my own grad students. The accolades had come to him again in great and deserving waves, yet Brad never acted like he’d done anything extraordinary. Aliens in the Prime of Their Lives had just become a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award in 2011, but when I got him on the phone to congratulate him, he wanted to talk about my work rather than his. He also wanted to put in a good word for a student of his who’d applied to the M.F.A. program where I teach. It was incredible. As I write this now, I realize that Brad had also won a Guggenheim and O’Henry around this time, a fact I found on Google because he never once brought it up in conversation.

The last time I saw Brad was shortly after Miss Jane, his last book, was published. I’d been asked to moderate a panel he was on at the Mississippi Book Festival. I had read the novel and loved it but had not yet told Brad this news. We met up at the hotel bar the night before the panel and, after a quick hug and order of bourbon, I began to gush about the book so earnestly that I felt almost embarrassed. However, I needed to tell him, and I want to state this as clearly as I can: I believe Miss Jane to be a masterpiece of American literature. It is as remarkable as any book to ever come out of the South.

A story based on his own great aunt, a woman born in Depression-era Mississippi with a rare genital abnormality that made her incontinent for life, I knew Brad had worked on this book for over thirteen years. Miss Jane is a novel about a person’s entire life, from its first beginning on earth to its last new beginning possibly elsewhere, and is so richly imagined and empathetically spun that I couldn’t believe I knew the person who’d written it. I told him how it almost pained me with its beauty, and even recited a moment to him from the novel I will never forget. It is when Jane, still a child and only beginning to truly understand the difference between herself and others, looks out of the kitchen window and feels a “strange presence” lock into her consciousness, one that is “like no one else’s in the world … and it sent a current into her spine up into the base of her neck, the tingling of it coming out of her eyes in invisible little needles of light indistinguishable from the light of the gathering day.”

“My God,” I told him. “I just read that part it over and over. It killed me.”

“I remember where I was when I wrote that,” he said. “I was living in Oxford, staying at that house. That’s probably around the time we first met.”

This exchange clarified, for me, the reason I so much admire Brad Watson’s craft. That line about the light from her eyes had come to him over a decade before and he had written it down and recognized its obvious beauty yet kept it close to his chest like one does a jewel. He went on to move between cities and states with it there by his heart, to write other stories, to win awards and fellowships, and in all that time had not pawned it for a quick payoff, but instead held onto the glowing image like a parent does a child, until it is ready to move on its own through the world. I was awed.

So, I told him what I am about to tell you.

If I could have any career as a writer, I would choose Brad Watson’s. One reason for this may seem obvious, in that every novel he ever published was a finalist for the National Book Award (Miss Jane joined The Heaven of Mercury with that distinction in 2016). Yet, that’s not it. Instead, it is that Brad seemed able to do what so few writers can; he never let his ego rush the story. He did not grab for the low-hanging fruit. He was patient with his characters, with himself, and kind to everyone else in the process. How many writers with that kind of early acclaim, I wonder, would go fourteen years between novels? Only those, it seems to me, both bold enough to recognize their own greatness and humble enough to await its return.

When I told him this, he said, “Yeah, but I’ve never made the best seller lists. I don’t know. I always wanted to write just one book that was read.”

And, of course, he was read, but that is the terrible thing about space and time. When budding writers are sitting at home, reading a book by their favorite author, making notes on their favorite lines, the author is often sitting hundreds of miles away at their own home unaware, wondering if they will ever write anything good.

*

Yet my clearest memory of Brad has nothing to do with his work. It is instead of a time right after I met him, in Oxford, when I was in love with a woman as well. My wife and I had gone out to dinner at a sushi place in town called Two Stick and saw Brad standing by himself near the host stand. We asked jokingly if he wanted to join us, under the impression he likely had a hundred more important people to see, and he unexpectedly said yes. We were led to a low table where we sat cross-legged on the floor on big cushions and what you need to know, I suppose, is that writers are not always friendly. The more accomplished ones can pick up a habit, it seems, of looking over your head instead of into your eyes in public places. It’s as if they are waiting for another famous writer, perhaps their missing twin, to walk in. Yet Brad sat with my wife and me for hours and talked as openly as a person can. He asked my wife about her family, her interests, and talked to us about the people he missed. His love for these people was obvious and vulnerable and his grin, gap-toothed and welcoming, made us hope the night would not end. My wife, who has now been to enough readings and book launches to have a rock-solid idea about how some writers behave, was also struck by how genuine he was.

So, when I found out about Brad’s death, I called her to tell her. I was out of town, but the news had reached me through the grapevine of Southern writers like Tom Franklin, Michael Knight, and George Singleton, as if each was a pallbearer of Brad’s name. By the time I got her on the phone I was crying.

She listened to me, consoled me, and said, “I’ll always remember that night at Two Stick. The three of us just sitting on the floor and talking. I remember his smile. He was so kind.”

“I know,” I told her. “I remember that, too.”

It was the night I discovered the writer I am always trying to be.

M.O. Walsh is the author of the novels My Sunshine Away and The Big Door Prize (September 2020, Putnam). He currently directs the creative writing workshop at the University of New Orleans.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3hOpGfk

Comments

Post a Comment