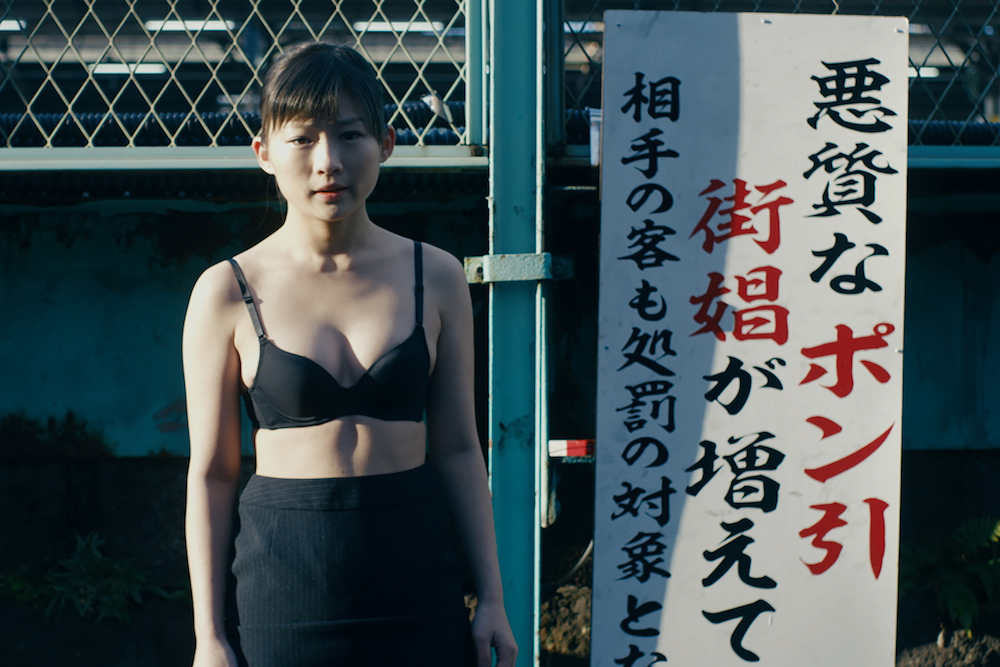

Life: Untitled, the 2019 directorial debut from Kana Yamada, is a film that bristles. (It is based on Yamada’s stage play.) Focusing on a contemporary Tokyo escort service called Crazy Bunny, it follows Kano, a young woman who initially attempts to become a sex worker as a way to escape what she explains are the constant failures inherent in an ordinary life. She panics during her first appointment and is instead reassigned as an employee on the office side of the service, scheduling client appointments and buying toilet paper. It’s through her eyes that we get to know the other people working there and the indignities and joys that make up their daily lives. Yamada is unflinching in her criticisms of contemporary Japan’s gender dynamics and sexism, and she asks dark questions about what the commodification of sex means for her characters, from the always-smiling Mahiru—who frequently remarks that she’d like to burn the entire city down and eventually reveals a history of sexual trauma—to Hagio, a male employee who sleeps with older customers on the side and holds nothing back in an ugly, judgmental monologue to Kano. The film is currently available to stream online in the U.S. until July 30 as part of the Japan Society’s annual Japan Cuts film festival. —Rhian Sasseen

In the sixties and seventies, New York City experienced a revolution in dance. George Balanchine and Merce Cunningham, who both still cast a long shadow over the art form today, were creating seminal works and new technical styles in ballet and modern, respectively. But the Western dance tradition was built on the marginalization of Black performers and the appropriation of their work, and neither of these men was inclined to make much change. The new aesthetics onstage instead reinforced the near-total exclusion of Black dancers from the mainstream. In the wake of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests, American dance companies are forced to reevaluate their programming and who makes up their ranks. But how will they approach the legacy of these midcentury icons going forward? I’ve been musing on this question ever since a dear friend and Cunningham aficionada shared two recent installments of the podcast Dance and Stuff. In these episodes, the hosts, Reid Bartelme and Jack Ferver, speak with three of the four Black male members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company: Michael Cole, Rashaun Mitchell, and Gus Solomons Jr (the fourth, Ulysses Dove, died in 1996). None of them overlapped in the company, and their conversation is correspondingly rich with shared experiences and differing opinions. Topics move from Cunningham’s failure to cultivate representation, to racial politics in the dance world at large, to touring with the company at the height of the civil rights movement. While a seemingly insurmountable amount of work remains to be done in order to make dance racially equitable, this conversation is a start. In response, the Cunningham Trust featured the podcast at the top of its July newsletter, noting that it is “committed to addressing the company’s problematic past and promoting diversity and inclusion through its current and future programming and resources.” —Elinor Hitt

There were some long summer afternoons in my childhood when only the crinkle of a library book’s plastic jacket could bring me back to earth. Books took me away from Maryland, and I particularly liked to read those that showed me there was more to do and say as a young woman than I had realized previously. For children of all ages, I wish a long afternoon this summer with Elizabeth Acevedo’s National Book Award–winning The Poet X. Both ambitious and fantastically self-explanatory, Acevedo’s YA novel in verse fills an Amazonian hole in the genre. Acevedo is a poet and began writing and performing poetry as a high school student in New York City. Reading The Poet X, I had the satisfying feeling that Acevedo is not only drawing from her own experience as a young person who found in poetry a language she’d been missing, but also writing to offer what she lacked for young people who are just finding that magic. The novel takes the form of a journal of poems written by a high school junior who finds her power in her own body, her own ideas, and in the performance of the verse she has been writing all along. With growing confidence and support, she gives her work the credence already given to her twin brother’s scientific accomplishments and her mother’s religious commitment. The poems are both satisfyingly complete and contiguous. I slipped through a whole chunk of the sizable hardcover with one arm still in my tote bag the other afternoon. So play yourself—or your young person—Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s rebuke of the patriarchy, and then order The Poet X and hear the message from both Bronx-born beacons: “I will not stay up late at night waiting for an apology.” But they may stay up to change the world. —Julia Berick

William Carlos Williams famously said:

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

He might as well have been talking about music, too. But it’s important to keep in mind that Williams said “difficult,” not “impossible”—because the news can be told in abstract narrative strokes, can bear emotional witness. I’m thinking today of the jazz trumpeter Ambrose Akinmusire’s powerful new album on the tender spot of every calloused moment. Could there be a better title for this, well, calloused moment, which, like the record, is full of hopeful stirrings, terrified rumblings, and passages of arresting intimacy and sometimes even beauty, calloused as a means of protection against the rampant injustice that each new day in Trump’s America brings? I’m being reductive—about both the moment and the record—but you get the point. Akinmusire is a wildly versatile player, capable of a Wynton Marsalis–like clarity of tone that slides into edgy, uneasy slurring worthy of Lester Bowie. His band has been playing together for a decade, and they’re ever in sync. This music is more guarded than their previous material, more volatile, and seems to be about so much that has happened in recent months—from lockdown and the uprisings following George Floyd’s murder to the current resurgence of the pandemic and the mind-splitting lead-up to the election—though the music was written and recorded well before. It’s another major movement in the soundtrack of now. —Craig Morgan Teicher

If nature takes revenge, the first to fall may well be those poets who reaped it for personal growth, who tortured it with similes and metaphors. Ya Shi will be saved: “This mountain valley is absolutely not a symbol,” he avows, “because I have touched it.” The poems in the astounding Floral Mutter—his first collection in English, translated with remarkable care by Nick Admussen—often start from a place of isolation, a mutual oblivion with the world. “I cannot say that I understand the valley / understand the petal-like, windborne unfolding of her confession,” he writes; later, he asks: “If god did just as he pleased / would the moon still whisper its secrets to wicked people?” Ya Shi, who teaches mathematics at a university, notes, “No matter how swift the bird, it cannot solve this math problem.” The opening sonnets are exquisitely alert to the landscape of Sichuan, to the mist on a lake, “the gem clatter / of spring water.” The land is mutable, strange, bound together through touch and sensation. He writes of lyric poetry as adultery, a poet’s “thirst to see herself in a dream, but without dreaming,” and traces the shared sentiment through laughter, suffering, and endless cigarettes to understanding, then boredom. His vision feels ever new; Ya Shi torches clichés like a divorcé tossing old love letters on the fire. There is also a sinuous melody to this collection that shows Admussen’s poetic hand. He maintains wordplay from the Chinese (“the Way that can waylay”) and even interweaves his own, in a manner that still feels true to Ya Shi. “In life we disturb too much dust. Death ends this reprehensible behavior,” Ya Shi writes, then offers a different view: “Life like light on dust, death like dust in light. / A particolored fantasy.” These sublime poems embody the ecstasy, the oddness of our entanglement with the world. —Chris Littlewood

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3hCCwxh

Comments

Post a Comment