In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

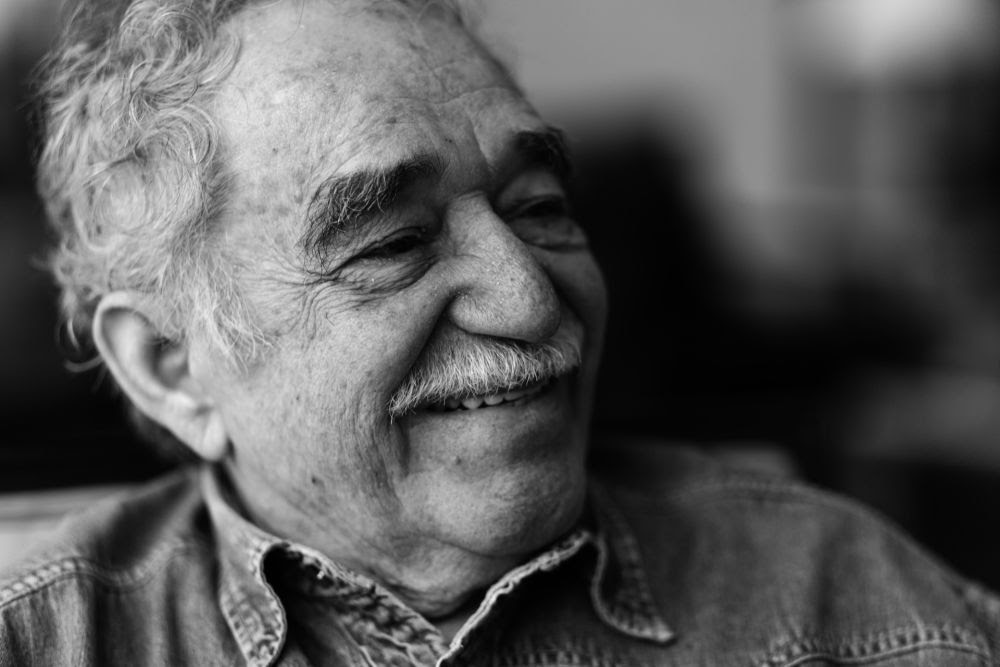

“As the pandemic set in, a peculiar thing happened to me: I found myself unable to read fiction, despite having always been drawn to novels and short stories over essays or poetry. I suppose I like the escapist element, or can appreciate a good lie; as Gabriel García Márquez, a former journalist, said in his Art of Fiction interview, ‘A novelist can do anything he wants so long as he makes people believe in it.’ In those early days of panic and uncertainty, the appeal of nonfiction, of facts, figures, and interviews—of real people and real events—was obvious. Public understanding of the coronavirus was murky at best, and I didn’t quite know who or what to believe. Months have passed since and we have learned more about the particulars of this disease, and how best to prevent its spread; I’ve also returned to reading fiction. But I still find myself intrigued by reportage, essay, documentary, and the like. This week’s Art of Distance highlights some of the boundary-pushing nonfiction that the Review has published over its sixty-seven years, and pokes at that sometimes tenuous border that separates fact from fiction. (It’s a border that has at times stretched and changed even within our own pages: this excerpt from Jean Genet’s novel A Thief’s Journal was published as a work of nonfiction in issue no. 13.) Read on for all the news that’s fit to print—or, at least, to be unlocked from the Paris Review archives.” —Rhian Sasseen, Engagement Editor

I’d be remiss if I didn’t open this survey with The Art of Nonfiction No. 1, in which Joan Didion speaks with Hilton Als. While Didion constantly dances between nonfiction and fiction (she was also the subject of an Art of Fiction interview), there is something especially fascinating in the way she describes the differences between the two genres: “Writing nonfiction is more like sculpture, a matter of shaping the research into the finished thing. Novels are like paintings, specifically watercolors. Every stroke you put down you have to go with.”

As I mentioned above, Gabriel García Márquez was a writer who worked in newspapers in the early days of his career; in this feature from the Winter 1996 issue, written by Silvana Paternostro, Márquez discusses his own reportaje, saying: “The strange episodes in my novels are all real, or they have a starting point, a basis in reality. Real life is always much more interesting than what we can invent.”

The question of classification, of what constitutes history or fabrication, comes up again and again in discussions of the work of W. G. Sebald, whose novels incorporate photos, facts, and real people and events in a way that stretches the already-elastic definition of the novel. Here, in this 1999 profile from issue no. 151—published just two years before Sebald’s unexpected death from a brain aneurysm while driving—the question of fact versus fiction comes up again: “Facts are troublesome,” he tells James Atlas. “The idea is to make it seem factual, though some of it might be invented.”

Of course, recording facts is a form of witnessing, too, and some writers weave facts together in works that, in their emotional complexity, are equal to any novel, such as the Belarusian writer Svetlana Alexievich, who creates literary collages out of interviews on subjects ranging from Chernobyl to the experiences of Soviet women in World War II. Her “Voices from Chernobyl” can be found in issue no. 172. And “Nineteen Days,” a series of diary entries from the dissident Chinese writer Liao Yiwu, published in the Summer 2009 issue, paints a clearer portrait of political repression in contemporary China through this record of events on June 4 each year from 1989 to 2009.

There’s plenty of more traditional on-the-ground reporting, too, such as Karl Taro Greenfeld’s “Wild Flavor,” which follows a worker named Fang Lin at the turn of the new millennium and the early days of the SARS outbreak in Shenzhen, China; some of these sentences are especially haunting to read now: “What terrified Fang Lin most when he was conscious was the sense that he was running out of air. No matter how freely he breathed, he felt that he was not inhaling oxygen but some other odorless, tasteless gas.”

Rounding out this selection is Sarah Manguso’s essay “Oceans,” from the Spring 2019 issue; it’s a series of fragmented meditations from the poet turned prose writer on the ocean, surgery, mortality, and the human body. You can also listen to Manguso read the essay on the second season of The Paris Review Podcast. And if you liked “Oceans,” don’t worry—our latest issue features another essay by Manguso.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3izFxj2

Comments

Post a Comment