William N. Copley (1919–1996), known by his signature name CPLY (pronounced “see-ply”), was a painter, writer, gallerist, art patron, publisher, and art entrepreneur. His work is held in private and public collections worldwide, such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Stedelijk Museum, and many more. Copley is now seen as a singular personage of postwar painting and an important link between European surrealism and American Pop art. In this excerpt from a new collection of Copley’s writings, he remembers the artist Joseph Cornell.

I knew Joseph Cornell just a little bit and saw him only a few times. To Julien Levy must go the credit for having discovered him as an artist. I can only take credit for having responded to him with a bang as early as about 1947.

As I remember, I met him as he was coming off an elevator and I was leaving the old Hugo Gallery, where I’d been with Iolas laying some groundwork for a gallery I was going to open in Beverly Hills. He was carrying two shopping bags full of boxes and Iolas must have introduced us, as I remember following them back into the gallery. I saw what was in the shopping bags and managed to buy an entire exhibition from Joseph—roughly fifty pieces. I think the deal was consummated at a nearby ice cream parlor. Cornell was gaunt and gray and shabby.

Being with him was like going down a rabbit hole, he was so like his boxes. Afterward, it seemed like it would be years before I would find my way back to wherever I left from that morning. Just to converse with him, one had to leave the familiar world and enter his. His world was very like Kafka’s Amerika.

The California exhibition was an enormous failure. I know it’s bad syntax to qualify a word like failure, but it applied in this case.

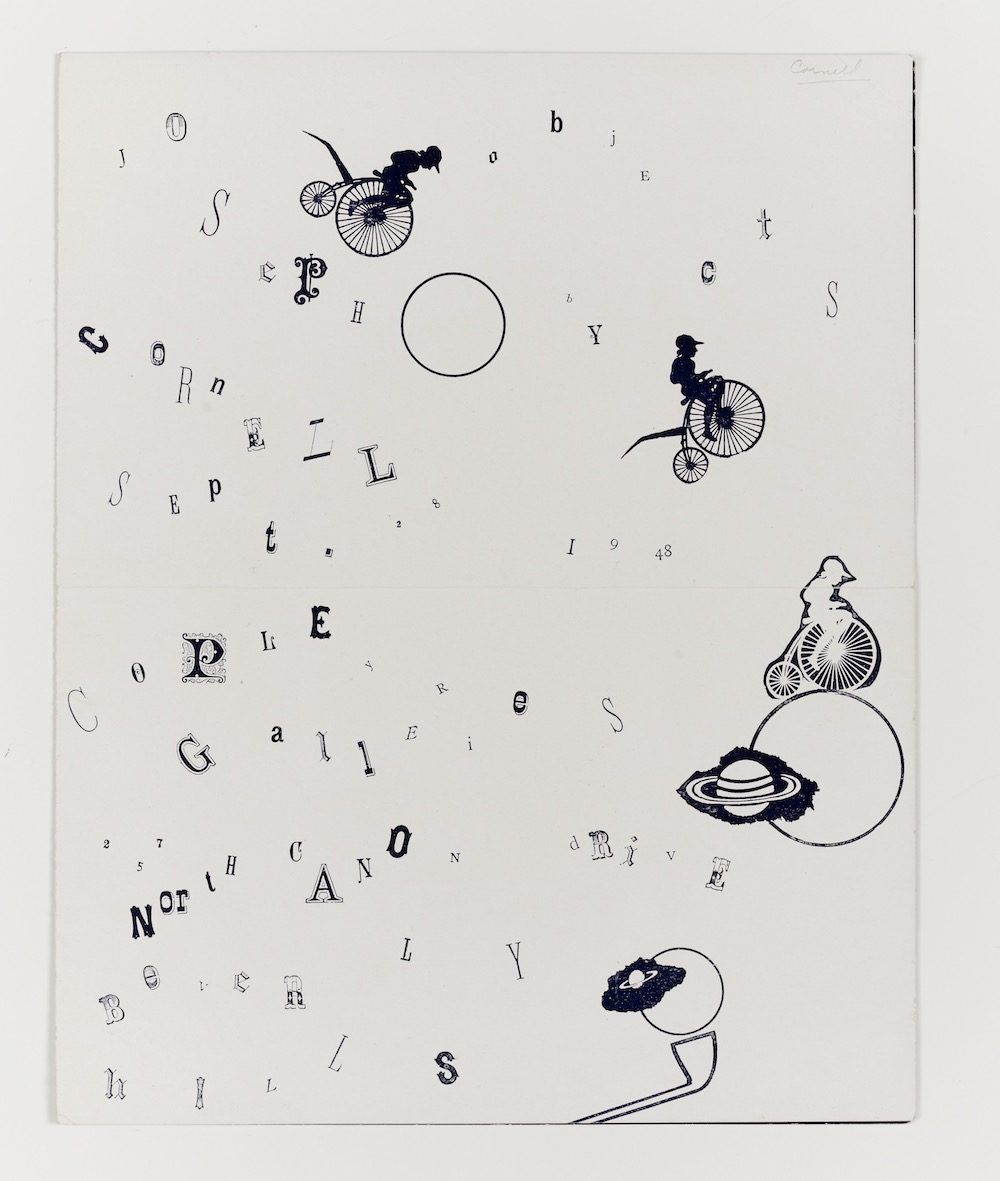

We’d designed a catalogue in what I considered to be Cornell blue and white. We rented a white high-wheel bicycle from a Hollywood prop rental and draped it in blue velvet. We displayed the boxes on glass shelves with clay pipes liberally dispersed. I couldn’t restrain myself going one step further and plastering the walls and then even the ceiling with the blue and white catalogues. Finally I was convinced that I’d turned the gallery into something of a Cornell box.

Announcement and exhibition catalogue for “Objects by Joseph Cornell,” Copley Galleries, 257 North Canon Drive, Beverly Hills, September 28–October 18, 1948.

What I didn’t figure was that most of us spend our lives fighting the idea of going into a box. People came, but they just looked in through the door. I remember somebody snottily saying, “I thought this was an art gallery.”

And it was really a very beautiful show. I would have bought it all myself except that I’d already bought it.

There was the American Rabbit quivering and waiting to be shot. There were the Taglioni Jewel Boxes, souvenirs of a great departed ballerina of whom it was said that she once danced boliki on the snow for brigands. Souvenirs too of Lucile Grahn, Alicia Markova, a homage to Swan Lake.

There were Soap Bubble Sets galore. There were books with cutout words or marbles in them seen through a window. There were butterflies occupying empty rooms. There were kaleidoscopes and boxes of multicolored sand. Round powder boxes too of the Nile (blue green) or Turkey full of tied-up bits of history pages to be assimilated like bonbons. There was Paolo and Francesca and Paul and Virginia necking secretly. There were the palaces with forests growing through their windows. There were the Pharmacy and the Beachcomber Bottles, the Thimble Garden for Alice in Wonderland and the Lobster Quadrille, the only hilarious piece I’ve ever known Cornell to do—boiled-red Coney Island celluloid lobsters in a mirrored chorus line. There was a paperweight of tight bound paper. There were pieces I almost don’t remember anymore.

And no one would set foot in that room. I was stuck with a lot of Cornell boxes. Cornell wouldn’t talk to me for three years afterward. He blamed the fiasco on my greed in doubling the prices he’d suggested—two hundred instead of a hundred dollars for the big ones.

The gallery failed a few months after that and I went to France to live out the disgrace. The Cornells went to sisters, cousins, and aunts, one of whom made lamps out of them.

I saw Joe a few more times after I was eventually forgiven. I remember a tea party at the Plaza. An attorney I knew from Chicago wanted to meet him and was a cautious collector. Cornell owned that he had an uncle who once got as far as Chicago. The attorney was the nondrinking kind and so they both needed their candies, pastries, and cakes for their blood sugar supply. All of a sudden there was a single cookie left. The conversation stopped completely (it hadn’t really gotten anywhere much anyway), and I noticed that there were four hostile eyes glued on the last cookie. I could smell the tension. The lawyer man from Chicago finally swooped down on the cookie. When Joseph left, he took all the cubes in the sugar bowl, and I happen to know he didn’t have a horse.

The last time l saw him was during a difficult time for him. He rather summoned me to Utopia Parkway as though he needed something from a friend. I’d always hoped to be invited there and while it had been mentioned before, this was the first and last visit to his domain. He wasn’t there when I arrived, though sweets were laid out. He’d left word with his brother that I could browse in his attic until he returned.

In the attic everything was in meticulous order. The sun boxes stood in a line next to Hotel D’Étoiles next to the Soap Bubble Sets next to … Occasionally there’d be a shock and a surprise. Anyway, it was an attic very full of boxes.

There was no way of knowing there was going to be a Cornell. No art historian ever prophesied the coming of the box. André Breton did make six boxes during his wartime stay in New York, but they could have been collages—they didn’t have to be boxes. Cornell’s boxes had to be boxes. His films lack the containment of form, no matter how fascinating they are. I feel his collages stay collages.

To me the only novels worth reading are the Bible and Moby Dick. Channel 13 was after all able to run even War and Peace as a soap opera.

I think of Queequeg in Moby Dick cheerfully working on the coffin which made it possible for Ishmael to tell his tale.

I think of the stars of Cornell’s theater—the Medici boy, Taglioni, his movie stars, his empty hotel rooms, the bird cage of the departed bird, Paolo and Francesca, Paul and Virginia, most of them gone to meet the maker. I see Joseph Cornell as our Queequeg, our little old coffin-maker. Beautiful boxes for beautiful things that don’t come back.

From William N. Copley: Selected Writings. © William N. Copley Estate / Artist’s Rights Society (ARS), NY. Reproduced with permission.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3hLrFS5

Comments

Post a Comment