The subtitle of Not a Novel, by the German writer Jenny Erpenbeck, is A Memoir in Pieces, but I think maybe the word shards would be more accurate—the texts collected here come from many eras and many moments and seem to fall around the reader like bits of glass, catching the light at different angles, complete in themselves but tied to one another to create a whole that is provisional and temporary and full of cracks. There is no trail of bread crumbs in this book, but somehow that makes it feel, as a memoir, even more real. The texts themselves share this tendency—“Open Bookkeeping,” which talks about her mother’s death, becomes a list of items inherited and lost, costs incurred and paid (a tax adviser tells Erpenbeck that her mother is due a refund of five euros); “On ‘The Old Child’ ” includes memories of its own earlier drafts and becomes a story about the imperatives and impossibilities of writing as a means of communication (“It isn’t always the case … that saying more brings us closer to the truth than saying less”). Translated by Kurt Beals, the book will be published next week by New Directions, and part of me expects it to land like a boulder on an iced-over river: there is something terrifying but liberating about seeing a person construct herself and her history in a way that feels so opposite to everything we are told. —Hasan Altaf

I spent a perfect sixteen minutes this past weekend watching the wonderful, curious, and gentle portrait John Was Trying to Contact Aliens on Netflix. John Shepherd spent half his life as a cosmic DJ, beaming Can, Art Blakey, Tangerine Dream, and Bola Sete into the night sky in the hope of making contact with extraterrestrials. Here, we meet him as an aging though still unconventional character who has abandoned his mission. Interleaved between segments of this contemporary interview is archival footage filmed during the brief period of novelty interest the media paid him many decades ago. When John was born, his father walked out on the family, and growing up, he had very little contact with his mother. He was adopted by his grandparents, who cared for him and raised him, and it was at their cottage in rural Michigan that Project S.T.R.A.T. (Special Telemetry Research and Tracking) was headquartered. We don’t hear from them directly, but their heartwarming support is everywhere in evidence: from old black-and-white pictures of them watching TV, surrounded by John’s astro-radio gear, to the revelation that a whole new annex was built—with their blessing and financial support—so that he could increase the power of his cosmic broadcast. Of course, higher towers and more powerful radio transmissions were never enough, and the viewer might begin to suspect that John was looking for more than alien life: “Sometimes, taking the course that I have in my life, and the path, is like a lonely mountain road to some higher elevation peaks, to see the view, to check out something most people don’t see. So you tend to go it alone more, you don’t have much company.” It is hardly a spoiler to reveal that he didn’t encounter alien life, though there is no sense here of failure. By the time the credits roll, it becomes clear that John’s search was, at least in some respects, a celestial success. —Robin Jones

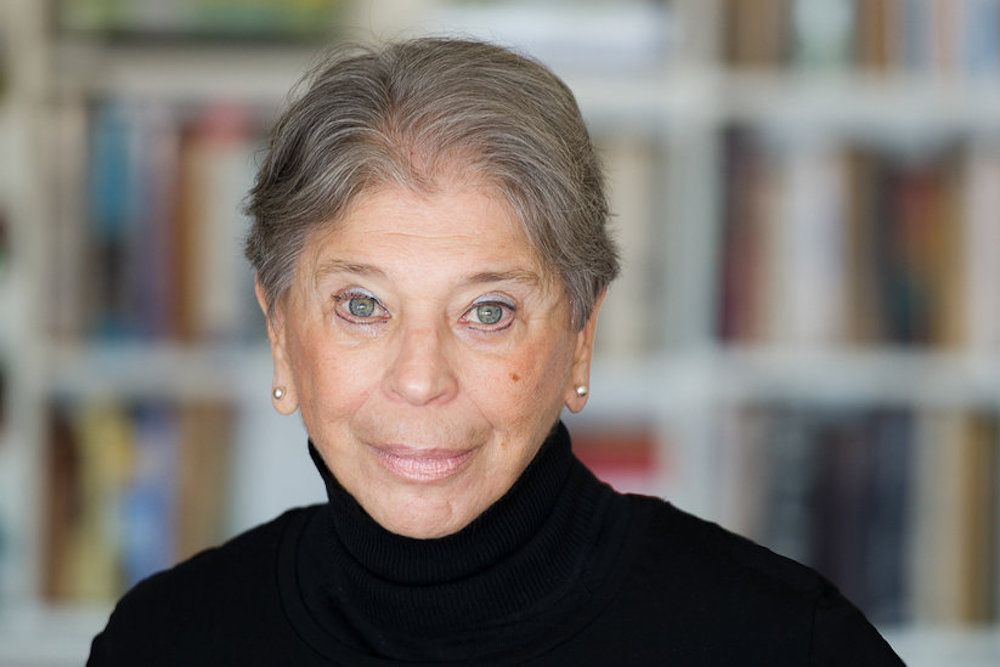

As I write this, I’m in the process of moving—not far, just down the road from my current apartment, and yet somehow this entire journey feels so overwhelming that it’s as though I’m traversing continents. Packing inevitably entails getting distracted by all the memories—and, most important, all the books—one has accumulated over the years in a single place, and so I’ve found myself sitting down and rereading paragraphs, pages, and chapters from favorite novels as I box them up. The pleasures of rereading are the subject of Vivian Gornick’s wonderful Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader, which was published earlier this year. In a series of nine essays that interweave autobiographical details that will be familiar to Gornick fans—her working-class childhood, her experiences writing for the Village Voice in the seventies—alongside readerly impressions both old and new, Gornick revisits the work of Marguerite Duras, D. H. Lawrence, Colette, Elizabeth Bowen, Natalia Ginzburg, and more. It’s a testament to how a reader’s life is, in a way, lived through books—memories as filtered through fiction. I already can’t wait to reread it—though maybe after unpacking a few boxes. —Rhian Sasseen

A few weeks back, a friend of mine told me about his recent reading of E. B. White’s “Death of a Pig” following the death of one of his own chickens. Now, I’d read plenty of White’s work in the past: the obligatory Charlotte’s Web in grade school, Elements of Style in high school, and “Here Is New York” toward the beginning of this global pandemic, when New York became its national epicenter. What I’ve learned about White’s writing, but more precisely his essays, in all this time is that he elevates the seemingly mundane and lends it space deep in his interiority. The pig’s death signifies personal weakness, individual shortcoming, but its death came prematurely; he had planned to butcher it later. Moreover, White didn’t cause the pig’s illness; it appeared seemingly out of thin air. Despite these facts, White coaxes the reader into a serene empathy through his own profound vulnerability buried in lean, gorgeous writing. This prosaic elegy mourns the loss of a living thing, a portion of White himself. My friend’s description of the recent death of his chicken followed the same tragic trajectory as White’s pig: confusion leading into a mounting loss of control. But White reveals that honestly recording the hopeless process allows us to reclaim some semblance of autonomy. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

On the surface, Raven Leilani’s Luster might seem familiar. Edie is a millennial with an uninspiring job in the publishing industry, a rat-infested Bushwick apartment, and a bank account that keeps teetering toward the red. She’s struggling to come of age in a world where adulthood holds little appeal beyond proving that one is capable of survival. Cross the disaffected wit of Halle Butler’s The New Me with the bold bodily grossness of Ottessa Moshfegh’s Eileen and the brazen sexual anger of Katherine Faw Morris’s Ultraluminous and you might get close. The past few years have been boom times for novels like this one, stories about young women who refuse to be docile, who revel in the takeout cartons strewn across their beds, and who use sex as a means of voracious, delicious self-destruction—self-destruction being the one thing over which they have agency. But beneath that veneer of trend, Luster feels new. For one thing, Edie, as she says in a tongue-in-cheek paraphrase of the language her date might use, “happens to be Black,” and her sharp analysis of race and class cuts through every interaction. For another, the novel grapples deeply with the very idea of surface, of what might lie beneath the breathless present tense of youth, the trappings that make up a life. As Edie finds herself at the center of a bizarre love triangle, invited into her older white lover’s New Jersey home by his wife, the connections she forms are anything but expected. More of a ghost than a guest, she observes and catalogues the minutiae of their lives, their scheduled weeknight sex and the gun beneath their bed. The prose wrestles Edie’s soul against this barrage of descriptors until the title, Luster, can be read only as a noun, not about sheen or sparkle but about what it means to be one who is driven by desire. —Nadja Spiegelman

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/2YJigTy

Comments

Post a Comment