In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“Many summertime rituals have been iced this year in the name of health and safety, including those of Hollywood. No big summer blockbusters for 2020; big-ticket movies have been postponed or sent straight to streaming. And while there is more content to watch on our laptops now than at any time in human history, I miss the movies: the chance to spend a few hours in the cineplex’s too-cold air conditioning, eating oversalted popcorn and watching something with a lot of explosions and/or dinosaur attacks. That being said, maybe even more than mall multiplexes and The Lost World, I’m missing my neighborhood theaters: I think it was at Village East—formerly a Yiddish theater, now on the National Register of Historic Places—that I saw my last film in theaters, a German epic inspired by the life of Gerhard Richter, Never Look Away. Little did I know those three-plus hours of huge cinematography, swelling music, and fraught, inspired narrative would have to last me awhile.

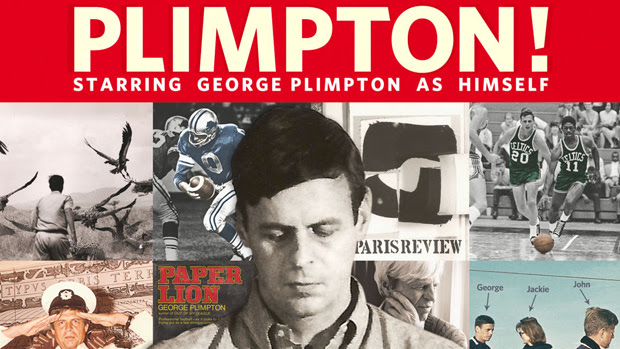

But! There is a bright side to this theater-free season: The Paris Review can take you to the movies, in some literary sense. Read on for unlocked fiction, poetry, and interviews that can transport you to the cineplex, and below, find details on our own streaming offering: Plimpton!, the documentary (a New York Times Critics’ Pick) about the magazine’s charismatic, intelligent, and always adventurous founder.” —Emily Nemens, Editor

There’s some COVID-appropriate hoarding in Rachel Khong’s “The Freshening,” but I highlight the story because the protagonist is also stuck at home, screening blockbusters in a suboptimal DIY cinema setup: “I took the ancient VCR from my closet. I plugged the cords into the television set. I had only four VHS tapes in my possession, and those, of course, were Supermans I through IV.”

The plot of The Virgin Suicides, the Jeffrey Eugenides short story that debuted in 1990 in The Paris Review, the subsequent novel, and the Sofia Coppola film, is summed up in the three-world title and summarily expanded in the story’s first line: “On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide—it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese—the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.” Of course, the how and why is why we read, and from this early glimpse of Eugenides’s first novel you can see a skilled storyteller recount the tragic tale of the Lisbon daughters with such empathy, wryness, and eye for detail that it nearly makes the camera redundant.

Go behind the camera with Claribel Alegría in her poem “Documentary,” translated from the Spanish. The poet calls the shots in an imagined documentary of her “wounded country,” and the reader views her shot list just as a camera might: “A panorama of iguanas, / chickens, / strips of meat, / wicker baskets, / piles of nances, / nisperos, / oranges.”

Deborah Eisenberg’s “Taj Mahal” looks at the film business from another angle: the familial. The narrator is offloaded on his filmmaker father, Anton Pavlak: “When I tell people that I was sent to stay with Pavlak during the heyday of his Hollywood period and I name some of the actresses who were likely to star in the breakfasts I had with him at his home, they look at me as if I’d said that my mother used to send me out to play with lions and tigers.” There are few felines here, but a good brunch scene—another thing that feels of another era.

The Paris Review has published a handful of Art of Screenwriting interviews, but in exploring that subcategory you might miss David Mamet, the wearer of many hats, who discusses his jump to moviemaking in his Art of Theater interview. “A lot of it, directing especially, is how many boxes are hidden in this drawing?”

And I’ll close with a reminder that there is a silver lining to watching movies at home—no annoying seatmates. As Chase Twichell reminds us in her poem “Bad Movie, Bad Audience,” sometimes that Chatty Cathy a few rows back can really be a drag.

This week, Paris Review readers have an exclusive opportunity to rent or purchase Plimpton!, the 2013 documentary about the founder and longtime editor of the Review, who was “one of the great adventurers of the 20th century.” The film was created by the team behind The Paris Review’s My First Time video series, and it follows George Plimpton “on a lifelong journey akin to fictional characters such as Forrest Gump and Indiana Jones. He hung out with U.S. Presidents, played quarterback for the Detroit Lions, forced Willie Mays to pop out in Yankee Stadium … played goalie for the Boston Bruins, struck the triangle for the New York Philharmonic and acted alongside John Wayne, Warren Beatty and Matt Damon,” all while editing the Review. May this film offer you some meaningful distraction and insight into the life of an iconic literary figure. A portion of the proceeds from every digital rental goes to support The Paris Review, a 501(c)(3), so please consider watching early and often.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3gpuAiL

Comments

Post a Comment