In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

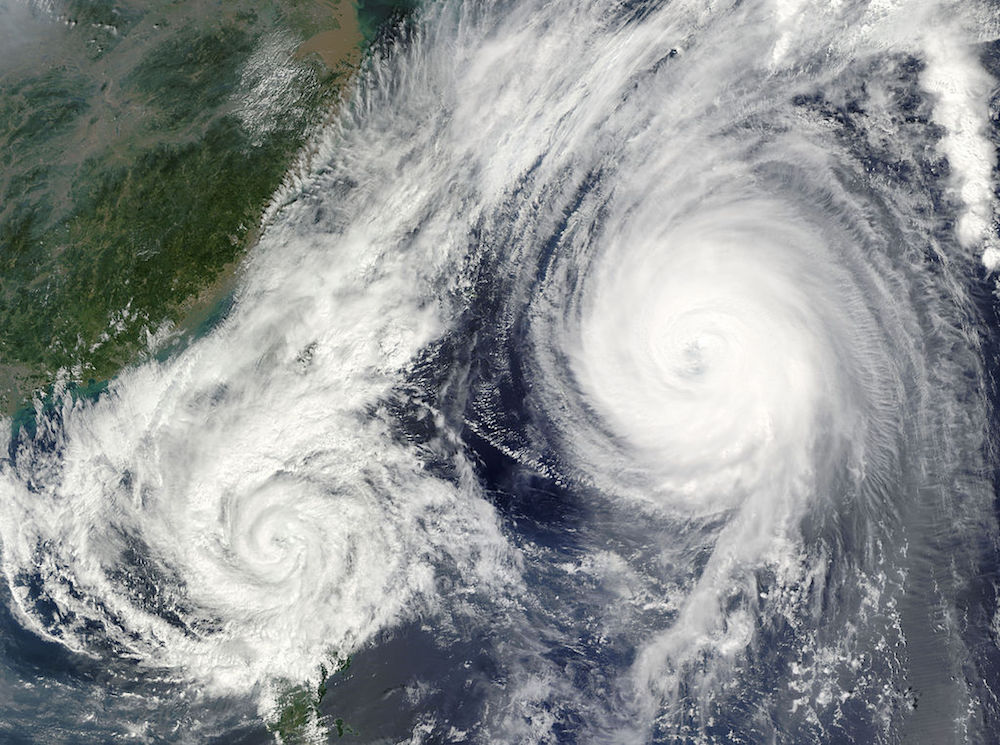

“Last week I wrote about the relative calm of the dog days of summer in NYC. But these same days of languor are hardly that elsewhere around the country and the globe. Wednesday I was rooting for Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season at the International Booker Prizes while Hurricane Laura bore down on Louisiana and Texas—a disconcerting coincidence, to say the least. The storm dissipated more quickly than expected, but that did not make its landfall in southwest Louisiana any less destructive. Earlier this month I felt an eerie prescience welcoming the publication of Shruti Swamy’s debut collection, A House Is a Body (we published the title story, about a mother’s evacuation from a wildfire, in 2018), as California fires flared again. And until a few weeks ago, the only derecho I knew was dance partner to izquierda. The Art of Distance began as a meditation on our social distancing during the COVID crisis, but this week, that same framework seems to emphasize the distance between here and there, the dichotomous feeling of at once wanting to rush in and help and feeling grateful to be out of harm’s way. But even from afar, we may find inspiration and empathy in literature that stares these disasters in the face, marks their dimensions with incisiveness and artfulness, and, sometimes, even imagines a way forward.” —Emily Nemens, Editor

Saturday marked the fifteenth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Claudia Rankine discusses writing in response to the disaster in her Art of Poetry interview.

“They Called Her the Witch,” excerpted from Melchor’s Hurricane Season, explains the trauma of the land on which the Witch lives and grows her poisonous herbs: “They lost everything, right down to the stones of their temples, which ended up buried in the mountainside in the hurricane of ’78, after the landslide, after the avalanche of mud that swamped more than a hundred locals from La Matosa.”

It’s a torrential rain that opens Denis Johnson’s “Car-Crash while Hitchhiking”: “The downpour raked the asphalt and gurgled in the ruts … My jaw ached. I knew every raindrop by its name.”

The protagonist of Shruti Swamy’s “A House Is a Body” first notices “not the scent of the smoke, but the sight of it, not the sight itself, but the screen through which it altered the sunlight.”

“It is because my husband is from the midwest / that he dreams of twisters,” writes Karen Fish in “The Dreams.”

Whiteout snow comes for Alice and her husband in Willa C. Richards’s “Failure to Thrive”—a story that was just republished in Best Debut Short Stories 2020.

In “Diary of a Fire Lookout,” Philip Connors describes the history of forest fire: “An ancient juniper from the heart of the Gila shows that fire burned around it, on average, every seven years; fire helped it thrive. Ponderosa covered much of the forest in open parkland with trees forty to sixty feet apart, surrounded by grass. Then, in the nineteenth century, the cow arrived.”

In “Storm and After,” Alexander Craig describes the chaos of a storm and the subsequent daybreak, “glistening and slate-gray.”

To support people recovering from natural disasters, please consider making a donation to the American Red Cross.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/34R5vKG

Comments

Post a Comment