“The property they [developers] built on had been farmland, overlooked by a big rickety-looking wood frame house,” the science fiction writer William Gibson tells me of his time living in a Charlotte, North Carolina, suburb (“on Blackberry Circle, where all the homes seem to have been built in 1954”) that today is called Collingwood. “I once referred to it [the farmer’s home] as a poor people’s house, and my father corrected me, saying that they [the farmer who owned the land] had lots more money than we did, because they’d sold the rest of their land to the company he worked for, which had built the development,” he recalls of the property the homes were built on.

Gibson once described living in that suburb as “like living on Mars,” with no grass and orange clay all around. I remember reading that and thinking about how much his suburban experience sounded like an old sci-fi story.

In the eighties, Gibson introduced readers to a burgeoning strain of science fiction dubbed “cyberpunk,” a noirish, computer-and-technology-choked futurescape. Nearly forty years after his groundbreaking 1984 novel, Neuromancer, some would describe Gibson as a modern-day prophet. Set largely in the Boston-Atlanta Metropolitan Axis (basically the bulk of the eastern seaboard), Neuromancer depicts a near future affected by war, environmental catastrophe, huge wealth gaps, dependence on the internet, and people looking for any way to dull the pain, from drugs to entertainment. The nickname for this area is “the Sprawl,” and it always struck me as a sad, lonely place.

Gibson’s vision influenced Anthony Bourdain. He describes the “amazing sprawl” of Tokyo in his book Kitchen Confidential as “something out of William Gibson,” planned to build a food court influenced by cyberpunk literature and movies, and told the New York Times that while he typically avoided most science fiction, he read Gibson. I related to that because, even though I went through my own short-lived sci-fi phase as a kid, what really stuck with and helped mold my views of the world from my teenage years to the present day was reading stories by J. G. Ballard or Philip K. Dick and watching movies like Akira and Blade Runner; but especially Gibson. I distinctly recall being around fifteen, sitting in the back seat of a car as we drove down some stretch of suburban road that never seemed to end, just miles of power lines, chain stores, and flashing lights everywhere, thinking of Gibson’s books. The orange of Home Depot gave way to the gray and blue of the Ford dealership, which gave way to a Toyota dealership, a used auto lot, car horn honking mixed with whatever was playing on the radio as the soundtrack.

I can tell you exactly where I was, but really I could’ve been nearly anywhere in America, and as I got older I realized it could’ve been on almost any continent as well. In my young, early-nineties mind—after I first read Neuromancer and right before I had internet access and other opportunities to read about Gibson and his work—I concluded that what I was passing was indeed the sprawl Gibson wrote about.

I was a teen; I’d already started turning into the angsty, angry kid who liked punk and skateboarding. But that was one of those “Ah-ha!” moments where I started thinking about things—namely, the suburbs—in a different way. And that wasn’t the only place where Gibson’s vision influenced me, and others. Around the time I first read Neuromancer, I also picked up the album Daydream Nation by the band Sonic Youth, and found myself particularly fascinated by the song called, yes, “The Sprawl.” It was only years later that the song’s writer, Kim Gordon, confirmed in her memoir that the song was indeed influenced by Gibson. She wrote, “The whole time I was writing [‘The Sprawl’], I was thinking back on what it felt like being a teenager in Southern California, paralyzed by the still, unending sprawl of L.A., feeling all alone on the sidewalk, the pavement’s plainness so dull and ugly it almost made me nauseous, the sun and good weather so assembly-line unchanging it made my whole body tense.”

I related to all these things because I’m a product of the sprawl. My childhood was, for all intents and purposes, an unhappy one. My parents divorced when I was young, and I experienced mental and physical abuse from them growing up. Around the time Gibson and Sonic Youth came into my life, I was a bored, anxious, alienated teenager going from one medication to another to try to “fix” (as doctors and my parents put it) my ADHD and depression. I didn’t have a lot of friends who went to my high school, but around age thirteen, when I went home, I found some semblance of community with the screen names in AOL chat rooms. Cyberspace, a term Gibson coined in the 1982 short story “Burning Chrome,” became my salvation. It made me realize I wasn’t alone on my little street in the suburbs, and that suburbia wasn’t for me. My story really isn’t that different from the stories of countless other Generation X and Millennial kids, and all these years later, I can perfectly picture that drive through the sprawl, and it serves as a symbol of when I decided I needed to get away. Every person who wants to get out of, or starts to despise, the suburbs has their reasons. Bourdain’s suburban childhood seemed, in his own words, pretty calm; his memoir points to the childhood family trips he took to Europe as opening him up to the larger world. Gibson wasn’t as much a product of modern suburbia as Bourdain, but he experienced it enough in its early stages, enough to leave an impression. “I imagine we were living in what had been the ‘model home,’ for selling other, unbuilt lots,” he tells me over Twitter DMs. “At the very start of our stay, most of the land around us was still raw N.C. orange clay. My first experience of home air conditioning.”

When Gibson was a child, his father worked middle management for a construction company that went from building structures for the government during World War II to developing subdivisions after it. Gibson’s childhood was during the boom times, the future-thinking times of cars that looked like rocket ships, of toy metal robots, of The Day the Earth Stood Still and Invasion of the Body Snatchers playing on the big screen, and pulp magazines at drugstores offering stories of alien invasions and explorations of other worlds. The wide-open future was the great promise to Gibson and his generation, and he got to see the beginning of it pretty much firsthand. The house he talked about, the one without grass, was a show home the family lived in for a time in North Carolina. They moved around a lot, and Gibson’s father was often away on business, scouting new locations for new suburbs. It was on one of those business trips, when Gibson was six years old, that his father choked to death, prompting his heartbroken mother to move her son back to the small Virginia town she was from, which Gibson once described as “a place where modernity had arrived to some extent but was deeply distrusted.” He was pulled from the suburbs and the future back into a rural part of America that was stuck in the past.

His mother would eventually ship her only child off to a private boys’ school in Arizona when he was fifteen. Three years later, she would also pass away. In 1967, after a few years of traveling and immersing himself in the counterculture, Gibson moved to Canada to avoid the draft. He eventually went to college in Vancouver and in the late seventies started writing science fiction. The time in the developing neighborhood in North Carolina, he tells me, “was my only personal experience of suburban living, as it happened.”

While Gibson says the Sprawl was “a vision of a big, bad metropolis,” his fictional idea of the future and the progression of the real suburbs are eerily similar. And driving through the Long Island hamlet considered the first modern suburb (and the model for the subdivisions his father’s company built, Gibson notes), I can’t help thinking the Sprawl had a different starting point, and it was Levittown.

*

Gibson didn’t coin the term sprawl; it started popping up around the time he was born. One of the earliest known uses of the phrase “urban sprawl” was in a 1947 article in Geographical Journal entitled “The Industrialization of Oxford.” So when we talk about sprawl, we’re thinking of an almost entirely postwar concept.

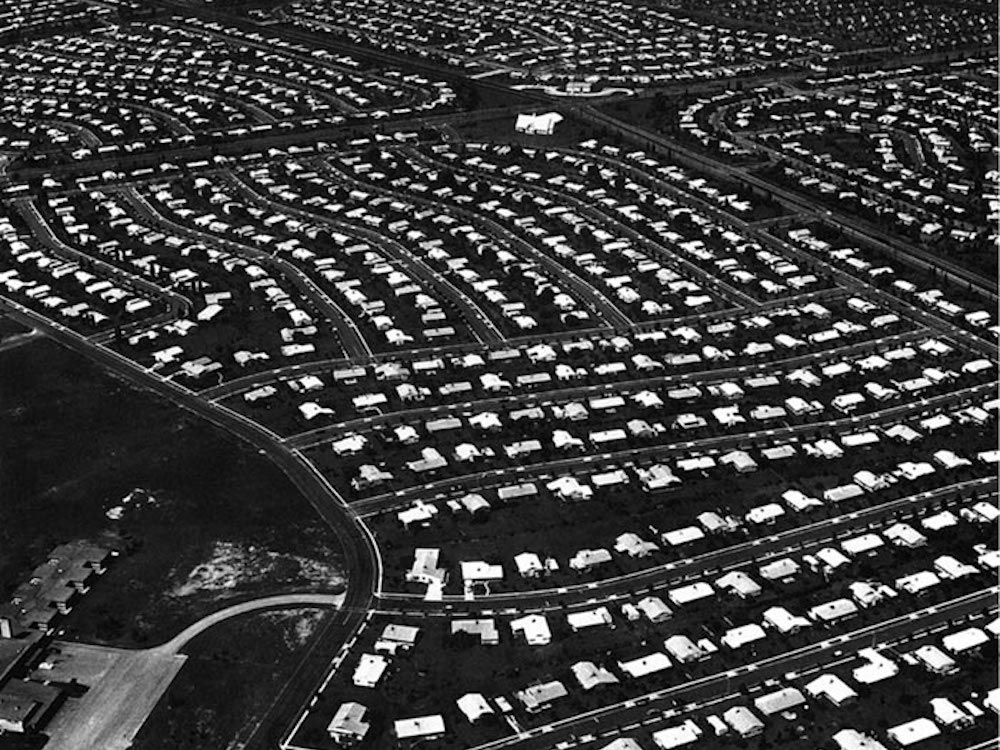

Sprawl is rows and rows of nearly identical houses with a little space between. It’s driving away from the houses (and you usually have to drive) and finding large commercial and industrial areas, box stores, and business parks. Sprawl goes on for miles, stretching into cities and suburbs in every direction. It feels claustrophobic, like it’s all pushed together. This is exactly how I’d describe Levittown to somebody who hasn’t been there.

One of the first things you see driving into Levittown on the Hempstead Turnpike is the OTB. Off-track betting parlors went extinct in New York City in 2010, but there it is, three letters bigger than the wooden WELCOME TO LEVITTOWN sign a few feet away. The crowd of patrons, mostly older men, sit and bet on horses on a two-lane street that’s still technically the turnpike. It’s one long row of businesses, then there’s a curve and you can either turn onto the continuing turnpike (NY-24) or straight onto Wolcott Road.

If you happen to be at the OTB and want a coffee at the Starbucks across the street, or maybe some snacks from the gas station next to it, you have to cross nearly ten lanes of traffic. But chances are you wouldn’t because the stretch of road is one of the most dangerous in Long Island. This is the heart of Levittown: a long road of businesses—many of them of the big box store variety—lined up to watch a parade of congestion inch past.

It’s suburban sprawl, yes, but Levittown also calls to mind what the architect Rem Koolhaas dubs “junkspace”—ugly, bland, utilitarian buildings and a lot of things that serve very little purpose. “Junkspace is the sum total of our current achievement,” Koolhaas writes. “We have built more than all previous generations put together.” The buildings I see in Levittown and many other suburbs are often just that, buildings. They serve little purpose other than to house things, with little thought put into the design; it’s all function over form.

To Koolhaas, the traffic is junkspace, the little stores are junkspace, and, in a very Gibson-esqe way, he believes that someday soon, “Junkspace will assume responsibility for pleasure and religion, exposure and intimacy, public life and privacy.” I’m just looking for something, anything, a little interesting in Levittown, whatever it takes to break up the monotony. As somebody who grew up in suburbs that came after William Levitt’s vision was complete, I’m used to suburban humdrum and the ennui it can conjure; but seeing the starting point of this modern condition puts it into a unique perspective.

Driving into Levittown the first few times is a suffocating experience. The roads are long. Unidentified wires (telephone? electrical?) hang low at certain points as you drive down the turnpike (“low” as in a few feet above my car, like they fell from a higher perch and nobody hung them back up). Smaller abandoned storefronts sit in the shadow of larger chains like Petco and Staples. Many of the buildings along the road look worn down. But when you turn into the residential areas—down Shelter Lane, Pond Lane, Grove Lane, Penny Lane, Beaver Lane, and many other streets dubbed “something” Lane—you still see a lot of the white picket fences that were part of the package in October 1947, when Theodore and Patricia Bladykas and their twin toddlers, Patricia Ann and Betty Ann, entered their new home in the planned community that would be called Levittown six months later. The fence came with the new washer and dryer, stove, refrigerator, and stainless steel cabinets shown off in the August 23, 1948, issue of Life magazine in a profile on developer William J. Levitt, president of Levitt & Sons and, according to the magazine, “the Nation’s Biggest Housebuilder.” At the time, the Levitts had built four thousand houses in a year on a thousand acres of land that was once a potato farm. It was the first of what we consider the modern suburbs.

Using assembly-line tactics out of Henry Ford’s playbook (not to mention “unskilled” and nonunion labor), Levitt sold the four-room Cape Cod cottages for $7,900 each (adjusted for inflation, that’s under $85,000 today, an affordable price to some returning soldiers thanks to the GI Bill). They came as they were, you couldn’t build an addition to your property, and you were tasked with the upkeep, from mowing your lawn to making sure the fence stayed white. Around the same time as the glowing reports of William Levitt’s vision, the real legacy of Levittown started to take shape, the one that, like the fence maintenance, was meant to keep it as white as possible: clause 25 of the houses’ leases, which banned occupancy “by any person other than members of the Caucasian race” save for “domestic servants,” was taken out after a group called the Committee to End Discrimination fought to have it removed. They were successful in having the clause taken out, but Levitt didn’t change his policies regarding who he’d sell or lease to, saying, “The plain fact is that most whites prefer not to live in mixed communities.”

The Levittown color barrier wasn’t broken until 1957, when residents in the second Levittown outside Philadelphia arranged a private sale of a home to Daisy and Bill Myers, an African American couple. In a picture from the family’s move-in day, August 13, 1957, you see the remnants of a mob that tried to protest their arrival on Deepgreen Lane—about twenty-five white people surround the house, which a couple of police officers guarded as the family tried to settle in. Some would argue that Levitt was just bound by his times, that federally sponsored acts like “redlining,” which began with the National Housing Act of 1934 and kept African Americans from living in mostly white areas, were in place before the first white fence. Levitt himself would defend his decision, writing once, “The Negroes in America are trying to do in 400 years what the Jews in the world have not wholly accomplished in 600 years,” going on to say, “As a Jew, I have no room in my mind or heart for racial prejudice. But I have come to know that if we sell one house to a Negro family, then 90 or 95 percent of our white customers will not buy into the community. This is their attitude, not ours.” Of course, what Levitt left out was that he and his family had built an even more exclusive—and exclusionary—community in the Long Island town of Manhasset.

Strathmore Vanderbilt stood on a hundred acres of land sold to the Levitts by the Vanderbilts. When Levitt purchased the land from the Vanderbilts at the start of the thirties, his vision was to offer something not too far off from picturesque neighborhoods like Llewellyn Park in New Jersey and Lake Forest outside Chicago, with the old French chateau turned into a county club at the heart of it. To name the town, Levitt kept Vanderbilt (since few things signify success in America like the Vanderbilt name) and attached Strathmore, the WASPy name of the upscale Tudor-style homes the family sold for $14,000 each during the Great Depression (around $200,000 today). He probably didn’t call it Vanderbilt Levitt because, well, Levitt sounds too Jewish, and William Levitt didn’t sell Strathmore Vanderbilt property to Jews, African Americans, or other nonwhite groups.

As much as Levitt and others have tried to clear his name in the years since, the fact is, whether it was personal or truly a business decision, William Levitt kept people out, and that practice has endured to this day not just in the towns he created but in suburbia as a whole. Of course, as we’ve seen, the suburbs’ history of keeping certain people out is as old as the places themselves. Levitt just happened to be the first to bring the suburban dream to the masses, which means he was also the first to deny people that dream as well.

So, yes, Levittown kept people out like the earlier, even more exclusive suburbs that came before, like Roland Park and Lake Forest. But it’s the way Levittown was laid out—a design nearly every modern suburb would come to adopt—that helped foster a sense of not belonging in generations of people. Whereas God was in the details for places like Llewellyn Park, it’s the lack of those details, the uninspiring layout of our suburbs, that creates the sense of displacement when you move around Levittown or any number of the places it influenced.

*

Very little feels natural in Levittown; it’s a gloomy place. But most of all, it’s hard to shake that feeling of loneliness. Not so much like being stuck alone on some distant planet, as Gibson described the small suburb he lived in; more like another planet we colonized and built up, then sort of gave up on. There are stores and wide roads, power lines and big fences, but you rarely see people walking in Levittown unless they’re getting out of their car to go somewhere. There’s so much in Levittown, but there also isn’t much of anything. It isn’t the noirish cyberpunk future Gibson envisioned, but since it’s real life, it almost seems more depressing.

Jason Diamond is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn. His first book was Searching for John Hughes.

Used by permission from The Sprawl (Coffee House Press, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Jason Diamond.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/34Casqk

Comments

Post a Comment