Sabrina Orah Mark’s column, Happily, focuses on fairy tales and motherhood.

For days Foryst, my cat, seems to have something caught in his throat. I bring him to the vet. “It might be a twig,” I say. “Or a pebble.” “What’s the cat’s name?” she asks. “Foryst,” I say. “Forest,” I say again, “but with a ‘y’ where the ‘e’ should go.” The vet is quiet. “How old is Foryst?” she asks. “Thirteen,” I say. She looks in his mouth. “It hurts when he swallows,” I say. Foryst is still. The vet sees nothing. She listens to his heart, his lungs. She hears nothing. It suddenly makes no sense to me that she is a human. Why isn’t she a wolf with great big eyes and great big ears that are all the better to see him with? To hear him with? “I recommend bloodwork,” she says.

I put my face in Foryst’s fur. “Please tell me what’s wrong.” He is silent. There is something in his throat. A word or a dead leaf. I am sure of it.

The vet wants bloodwork. She wants the cold, definitive clink of numbers. I want Foryst to talk so he can tell me what hurts. I want him to cough up a dry spooked “O” and be suddenly healed. I want him to tell me the future. I call my mother. “There’s something stuck in Foryst’s throat.” “Of course there’s something stuck in Foryst’s throat,” she says. “Why wouldn’t there be something stuck in his throat? There’s something stuck in all of our throats.” She hangs up. I swallow once. I swallow twice.

When we get home, I open Foryst’s mouth and shine a flashlight down his throat. Something shines back, like a diamond in a cave. His teeth are hieroglyphs. I want to jot them down so I can read what’s inside him. I want to reach all the way in, but he snaps his mouth shut and growls.

I tell my husband there is something stuck in Foryst’s throat. “What?” he says. He lifts his left headphone from his ear. “There is something stuck in Foryst’s throat.” My husband is always wearing headphones. I say everything twice.

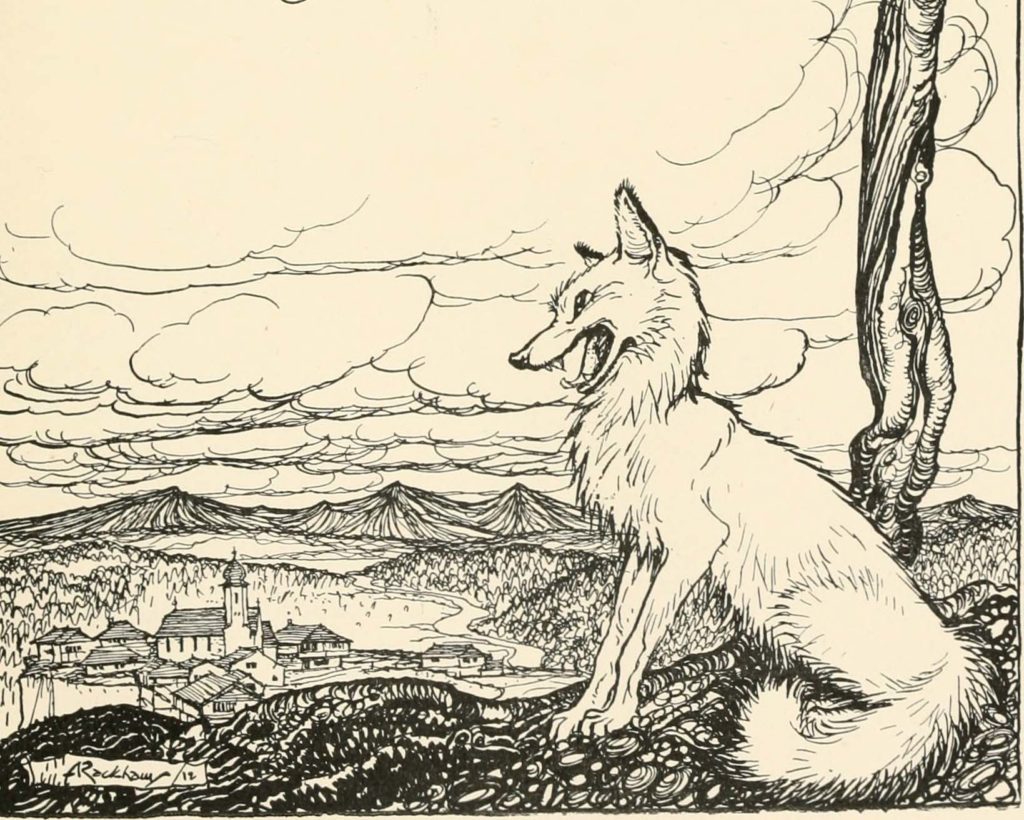

In fairytales animals are always talking. Even when they are dead, they are talking.

“Good night, Pinocchio,” says the ghost of The Talking Cricket. “May heaven protect you from morning dew and murderers.” Animals in fairytales are feral poets. Their words are overgrown and have the scent of soothsayer and pelt. When an animal speaks it’s often to spill the guts of the fairytale. To leak the plot and indict the antagonist. To clear up the past or tell the future. Animals are tattletalers and whistleblowers. “My mother, she killed me, / My father he ate me…” tweets the bird who is the dead boy in “The Juniper Tree.” “Roo, coo, coo, roo, coo, coo / blood’s in the shoe / the shoe’s too tight, / the real bride’s waiting another night,” sing the doves in “Cinderella.” “If this your mother knew, / her heart would break in two,” moans the horse’s head nailed beneath the dark gateway in “The Goose Girl.”

First there is a h-u-m. And then there is a h-u-m-a-n. And then there is an a-n. And then there is an a-n-i-m-a-l. Inside fairytales “hum” and “human” and “animal” gather like mist. Like humanimals who share a single language.

Outside fairytales the mist separates.

The first talking animal, as I was taught by the rabbis, was the snake. “If you eat the apple your eyes will be opened, and you’ll be like God,” says the snake, “knowing good from bad.” And so Eve ate the apple and knew what god knew. I ask Eli, my seven-year old, if he would ever want to know what god knows. “Of course not,” he says. “You would know so much it would be like knowing nothing at all.”

The only other animal who talks in the Bible is a donkey who sees an angel in the path of a vineyard. The donkey kneels down, and his master who does not see the angel hits him with a stick for kneeling. The master doesn’t see the angel because now that we know so much it’s like we know nothing at all. Now that we know so much we can barely see the angels.

Foryst surrounds me. He maintains his ability to speak without words. I talk, and I talk, and I talk to him. One of his ears tilts towards me, and the other tilts backwards as if catching something the soil just said to the soil.

“Do you think,” I ask my husband, “that fairytales are riddled with talking animals because they’re riddled with so little God?” “What?” he says. He lifts his left headphone from his ear. “Or is there so little God in fairytales because they’re riddled with so many talking animals?”

As the outbreak continues to spread, many of us are bringing animals home. This is not only because we are lonely, but because we know, as Kafka teaches us, that animals are “the receptacles for the forgotten.” Their silence evokes the silence of mourners. Nature, it seems, is trying to forget us. And if we must be forgotten let us bask in the glow of our animals. Let our fade be warmed by their fur. May the animals beside us keep us upright as we hobble into the future. What has climbed inside Foryst’s mouth might just be something trying to ward off oblivion. It might be something reminiscent of us all.

Kafka called his cough “the animal.” His herd of silence. As if Kafka’s cough was all of Kafka’s stories slowly forgetting Kafka.

Every night I ask my husband, “what is going to happen?” And every night he says, “what,” and lifts his left headphone from his ear. And then I say again, “what is going to happen,” leaving the first “what is going to happen,” suspended over our bed. And my husband says, “with what?” And every night I say, “with everything.” And every night he says, “I cannot tell you,” which sounds like he knows the answer and also sounds like he doesn’t know the answer. I wonder if prophets, like animals, must unname the present to see visions of the future.

I’m sorry. I meant to write a happy essay about what we learn from talking animals in fairytales only to realize we learn nothing from them because in fairytales animals remember everything. And now I’ve ended up writing about oblivion instead.

“What?” says my husband. “I’ve ended up writing about oblivion instead.”

Close to my house is a path called Rock and Shoals. It’s been raining forever and I am worried about what’s in Foryst’s throat and the end of the world and our democracy and illness and money and hate and so I decide to take a walk with my sons. The ground is thick with red and yellow and bright white mushrooms, and the trees are covered in giant snails. One tree seems so swollen, and its bark is shedding such big flakes, that I am not surprised when a child bursts out. She shakes off the tree from her white hair. She doesn’t speak because she is from a future fairytale where no one speaks, not even the animals. The girl, my sons, and I walk along the misty path. Her hands are badly rusted and her mouth flickers on and off. “Tell me how this ends,” I want to say, but my words aren’t words anymore but limp petals softer than powder. My sons open their mouths to speak but where their words should be are pale green animals with long, spindly newborn legs and round ancient faces. On the ground is a small blue feather but it isn’t small or blue or a feather because this is a fairytale with no words. I put it in my pocket to bring home, but there is no I or pocket or home because this is a fairytale with no words. This is a true story, but there is no true or story because this is a fairytale without words.

When my sons and I without the girl return home, whatever was in Foryst’s throat is gone. He looks at me and says, “This is how the story

Read earlier installments of Happily here.

Sabrina Orah Mark is the author of the poetry collections The Babies and Tsim Tsum. Wild Milk, her first book of fiction, is recently out from Dorothy, a publishing project. She lives, writes, and teaches in Athens, Georgia.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/3bF6aQp

Comments

Post a Comment