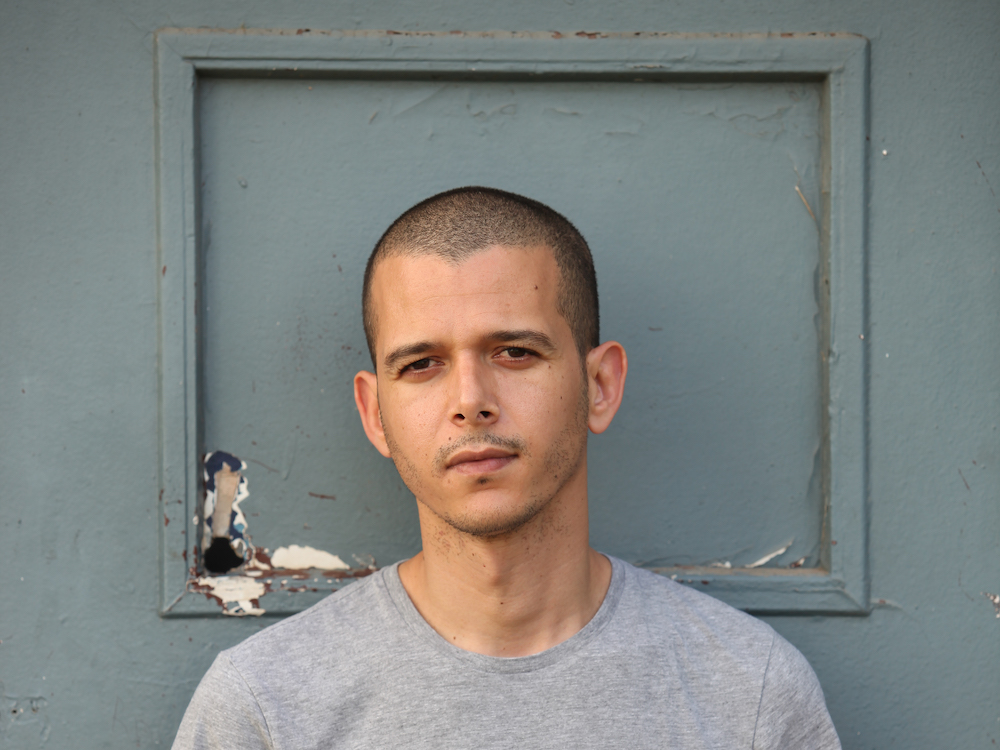

Evan Rachel Wood as Old Dolio Dyne in Miranda July’s Kajillionaire. Photo courtesy of Focus Features.

In California, you’re always waiting for the Big One. This shaky ground serves as the foundation for Miranda July’s latest film, Kajillionaire, in which the Big One could be either an earthquake or a windfall for an oddball family of three who get by pulling scams and living in the leaky office of a bubble factory. But that’s how they like it, the patriarch claims, saying: “Everybody wants to be a Kajillionaire. I prefer to just skim.” His twenty-six-year-old daughter, Old Dolio, has never known anything but this perpetual absence of money, comfort, and so-called “tender feeling.” Along comes Melanie, who tries to show Old Dolio a world beyond her parents. Small earthquakes anticipate Old Dolio’s reckoning, interrupting moments of potential intimacy. But little tendernesses urge her to crawl out from the bubble factory basement or the gas station bathroom stall. Even the simplest acts of affection are transcendent, surprising: getting her hair brushed, the word hon. Fans of July’s work will not be surprised by the strangeness—the intricate motions of the bodies, the strange encounters, the role-playing—but they might not expect the sense of resolution. This ending is hard earned, though. The cinematography brings out the precious moments of softness as the screen suddenly is overtaken by a sunspot and the soundscape swells. “I’m lucky … I won’t miss my life,” Old Dolio says when she thinks the Big One has come. She knows this is it, she says, because she’s always been told that when it comes, “it will be all dark all around.” Then she opens the door to blinding light. —Langa Chinyoka

Opinions abound about what to do with monuments that raise up perpetrators of slavery and colonialism. Toppling or otherwise removing seems elegantly simple and increasingly likely. The British artist Hew Locke, on the other hand—or rather at the same time—uses monuments to portray a more complex history of the men memorialized, the eras they inhabited, and the legacy that present-day viewers inherit. By layering paint and objects over large-scale photographs of statues, Locke adds weight and depth to hollow-cast figures. Thus, a Pilgrim’s iconically austere costume is bedazzled with lacy gold, jet beads, buffalo coins, and delicate but unmistakable chains. George Washington has cowrie shells in his hair, coins on his waistcoat, and shackled humans hanging from his wrists. The British slave trader and philanthropist Edward Colston looks pensive in his statue, which was recently thrown into Bristol Harbor by Black Lives Matter activists, but under Locke’s treatment, covered in gold, jewels, coins, and trading currencies, he appears to be huddling beneath the covers of his ill-gained wealth. This work acknowledges the indelibility of individual lives and acts—the subjects’ and the sculptors’—in all their tangled, tragic truth. Serendipitously, because Locke has never been allowed to execute his vision directly on the statues themselves—only on photo prints—his pieces may well outlast them. —Jane Breakell

The Moroccan writer Abdellah Taïa’s novel A Country for Dying (translated from the French by Emma Ramadan) depicts a Paris distinct from the stuff of Anglophone fantasies. The story follows three characters: Zahira, a forty-year-old Moroccan sex worker in love with a man who does not return her feelings; Zahira’s friend Zannouba, who undergoes gender confirmation surgery and reflects on questions of trauma and identity; and Mojtaba, a gay Iranian revolutionary who by chance stays with Zahira for the month of Ramadan. Taïa, who came out as gay in Morocco—where homosexuality is illegal—in 2006, poignantly portrays the lives of immigrants in a city and country that is frequently hostile to them, and openly questions France’s perception of itself and its immigration policies. —Rhian Sasseen

Art museums are opening, but who among us has not wandered alone the cavernous galleries of the Met wishing they’d taken those art history electives? Whither the visiting lecturers, the docents? The Frick Collection’s YouTube channel is here for our untrained eyes. Each installment of the Cocktails with a Curator video series spends about twenty minutes on a close reading of a painting, the perfect amount of time both to feel versed in the work and to treat oneself to the suggested drink pairing: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Portrait of Comtesse d’Haussonville gets an absinthe concoction, called the Jaded Countess, with a potency that matches the subject’s expression. Regarding Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl, the curator Aimee Ng says, “When I look at a Vermeer painting up close, I always get the sense that if I could just peel back this top layer of the craqueler, the natural cracking that happens to paintings … if I could only get past that layer, then I could see with absolute precision what was painted there.” For me, Cocktails with a Curator does exactly this. Other series on the channel include Travels with a Curator and What’s Her Story?, which focuses on women such as Audrey Munson, “America’s first supermodel,” whose likeness graces statues and sculptures across New York City. They also have the real meaty stuff, full lectures recorded in the time of auditorium gatherings (these are organized nicely on the Frick Collection’s website). It’s a collection unto itself, an energetic effort in art education and appreciation where the casual visitor can lose themselves to what’s on view. —Lauren Kane

At last, the new title from Supergiant Games, one of my favorite developers, has been released in full. Hades has you don the blood-red laurels of Zagreus—son of the Greek god Hades and prince of the underworld—as he tries to flee his father’s wretched domain. Along the way, the Olympian gods and various other classical figures such as Sisyphus and the Furies offer you their help or scorn. But in fighting your way through battle-ready shades, skeletons, and monsters, you quickly realize that any escape attempt at this point will end in death. You’re already in the underworld, though, so what does death really mean? It means a return to the bloody pool of souls in your father’s house, where he awaits to reprimand you for your foolishness. But the hacking and slashing are so fun, and hell is so infernal, that you might as well try again. And again. And again. Maybe you make it a bit farther this time, maybe you come up short that time, but there’s less exasperation in death than a strange joy in knowing you’ll get to talk to the fascinating characters in your father’s court once again, pet Cerberus one more time, and make yourself stronger for the next run. And once you’ve settled into the combat, you’ll soon find yourself engrossed in the classical drama unfolding among Zagreus, Hades, and the rest of the underworld. Between the gorgeous artwork and the phenomenal voice acting, you’ll also get sucked into the personal comedies and tragedies of each figure you meet along your journey, from Orpheus to a bashful Gorgon head named Dusa. And lastly, there’s the soundtrack, perhaps the most artful dimension of any Supergiant game—though everything else comes close. The studio’s in-house composer, Darren Korb, crafts a distinctive sound that brings the whole panorama together. In each of Supergiant’s previous works—Bastion, Transistor, and Pyre—the final ballad brought me to tears. I’ve yet to finish Hades, but I have no doubt Supergiant will do it again. —Carlos Zayas-Pons

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/331fM5q

Comments

Post a Comment