In March, The Paris Review launched The Art of Distance, a newsletter highlighting unlocked archive pieces that resonate with the staff of the magazine, quarantine-appropriate writing on the Daily, resources from our peer organizations, and more. Read Emily Nemens’s introductory letter here, and find the latest unlocked archive pieces below.

“In the before times, we’d celebrate the arrival of the new issue with a party at the office. I’d greet attendees by shouting from atop the pool table (barefoot to protect the felt), and I’d invite a contributor up to share the shortest of readings before the party got back underway. This past week, we gathered online instead of on Twenty-Seventh Street, and I (still barefoot) welcomed readers from my Alphabet City living room. Sure, I missed the mingling, the hugs and hellos, but at the same time I was grateful for the extra space and attention our new format offered, for both our writers and our readers: no one was shouting over bar sounds and, importantly, proximity to the A train wasn’t requisite for attendance. And as I told that night’s featured contributors—Eloghosa Osunde (calling in from Nigeria), Emma Hine (reading from Denver), Rabih Alameddine (speaking to us from San Francisco), and Lydia Davis (reading from upstate New York)—while it had been a joy to read (and edit) their pieces, I found it truly exceptional to hear those works read by their makers. The office parties were known to get a bit crowded, but on Wednesday, the room was fuller than ever, with hundreds of attendees across several continents. If you weren’t able to attend, have no fear: a recording of the program is available below, and we’ve unlocked several pieces related to the event. Another thing I said Wednesday that is worth stating again and again as this new normal takes shape: it is a welcome relief and a small joy to know that while so much is in flux, there is still literature, and it is within our reach to celebrate that writing, to embrace existing traditions and to create new ones.” —EN

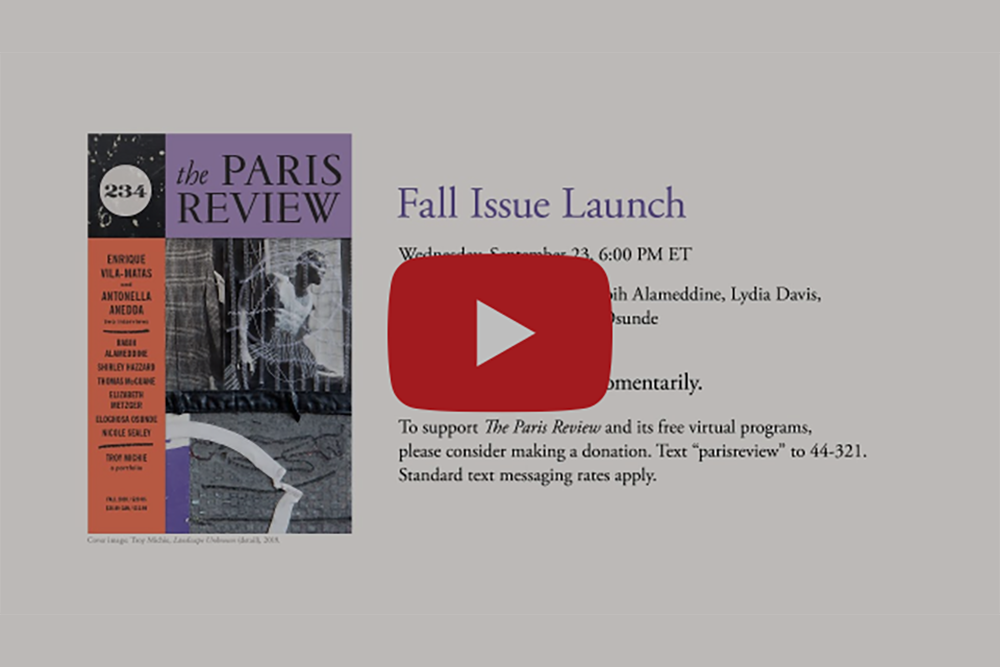

Read along while you watch the complete event on YouTube now!

Eloghosa Osunde’s “Good Boy” follows the journey of an unnamed protagonist as he builds a chosen family of queer friends in contemporary Nigeria. “I believe that the world we live in was first made, right?” Eloghosa says. “A big part of imagining other ways to be starts with the imagination, starts with what we write, starts with story.”

Emma Hine’s poems “Cassandra” and “Young Relics” are about families and homes. “My relationship with domestic spaces and objects is very talismanic,” she explains. “I have a lot of trouble separating the feeling of a memory from its location.”

Rabih Alameddine writes about Beirut and a family in crisis in “The July War,” a story he first drafted more than a decade ago, about the 2006 war in Lebanon. In discussing why he returned to the story this spring and why it felt relevant in 2020, he says: “What it had, and what I hadn’t concentrated on, was how people behave during crisis … how people react and behave when encountering sudden loss. How do we grieve? That story took on a new significance to me.”

Lydia Davis reads two stories, “An Incident on the Train” and “The Left Hand.” Listen to those, and then stick around for her conversation about cat literature.

Sign up here to receive a fresh installment of The Art of Distance in your inbox every Monday.

from The Paris Review https://ift.tt/30gd3Dm

Comments

Post a Comment